‘ . . . you know only

A heap of broken images . . .’

–T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land

I. Destruction

The description of the South as a land that has fallen into desolation is familiar to many. Sometimes this historical reality is presented to us in unfamiliar ways, however. For instance, in his short story ‘Jericho, Jericho, Jericho’, originally published in 1936, Andrew Lytle uses the allegory of a dying woman to explain what has happened to the South and why.

Kate McCowan, the widow of a man known in the story only as the General and the owner of a plantation named Long Gourd, is on her death bed. She is the personification of the Old South, both slowly making their way to the grave. But before they get there, they are desperate to impart to the rising generations the good traditions they have inherited from their ancestors. Ms Kate’s grandson Dick represents the young Southerners, the vessels the Old South is trying to prepare to receive the treasures of the past:

Soon now she would be all water, water and dust, lying in the burying ground between the cedar—and fire. She could smell her soul burning and see it. What a fire it would make below, dripping with sin, like a rag soaked in kerosene. But she had known what she was doing. And here was Long Gourd, all its fields intact, ready to be handed on, in better shape than when she took it over. Yes, she had known what she was doing. How long, she wondered, would his spirit hold up under the trials of planting, of cultivating, and of the gathering time, year in and year out—how would he hold up before so many springs and so many autumns. The thought of him giving orders, riding over the place, or rocking on the piazza, and a great pain would pin here heart to her backbone. She wanted him by her to train—there was so much for him to know: how the creek field was cold and must be planted late, and where the orchards would best hold their fruit, and where the frosts crept soonest—that now could never be (Stories: Alchemy and Others, Sewanee, Tenn., Univ. of the South, 1984, p. 6).

Mr Lytle gives us in this passage a more than subtle hint that some things had gone wrong in Southern life that would have to be answered for. We know that they are not the world-breaking evils that many on the Right and Left make them out to be. Nevertheless, we must be forthright in acknowledging them (and there are few nowadays who do not), lest the South endure more hardships than she already has.

In Mr Lytle’s view some of these evils include plantations that had become too big, and sometimes by unjust methods:

Four thousand acres of the richest land in the valley he would sell and squander…before the footboard the specter of an old sin rose up to mock her. How she had struggled to get this land and keep it together—through the War, the Reconstruction, and the pleasanter after days. For eighty-seven years she had suffered and slept and planned and rested and had pleasure in this valley, seventy of it, almost a turning century, on this place; and now that she must leave it…

The things she had done to keep it together. No. The one thing ..

. . .

“My husband won’t squander my property. You just want it for yourself.”

She cut through the scream with the sharp edge of her scorn: “What about that weakling’s farm in Madison? Who pays the taxes now?”

The girl had no answer to that. Desperate, she faced the lawyer: “Is there no way, sir, I can get my land from the clutches of this unnatural woman?”

The man coughed; the red rim of his eyes watered with embarrassment. “I’m afraid,” he cleared his throat, “you say you can’t raise the money . . . I’m afraid—”

That trapped look as the girl turned away. It had come back to her, now trapped in her bed. As a swoon spreads, she felt the desperate terror of weakness, more desperate where there has been strength. Did the girl see right? Had she stolen the land because she wanted it? (pgs. 12-3)

Also, the casualness with which punishment was meted out to the servants:

Well, sir, that morning Della was late. Ma had had to send for her twice, and she come in looken like the hornets stung her. She fluffed down to her sewen and went to work in a sullen way, her lip stuck out so far it looked swole….

Directly ma said, “Della, take out that seam and do it over again.”

“Take it out yourself, if it don’t suit,” she flounced back.

In a second pa was on his feet: “Woman, lay down that sewen and come with me.”

. . .

“I have whipped Della and sent her to the field for six months. If at the end of that time she has learned not to forget her manners, she may take up again her duties here. In the meantime, so you will not want, I’ve sent for P’niny. If you find her too old or in any way unsuitable, you may take your choice of the young girls” (‘Mr. MacGregor’, ibid., pgs. 58-9).

Because of these distortions in her life, the Southern plantation system had to be held together by unnatural means, which ended eventually in catastrophe. Mr Lytle uses the following images to illustrate. Ms McCowan is speaking:

“Old Mrs. Penter Matchem had two daughters with just such waists, but ’twarnt natural. She would tie their corset strings to the bed posts and whip’m out with a buggy whip. The poor girls never drew a hearty breath. Just to please that old woman’s vanity. She got paid in kind. It did something to Eliza’s bowels and she died before she was twenty. The other one never had any children. She used to whip’m out until they cried. I never liked that woman. She thought a whip could do anything” (‘Jericho’, p. 10).

As with Mrs. Matchem, so with the Old South: She used the whip and other constraints to keep the plantation system afloat, but as was said above, it did not bring about a good end. Indeed, like Ms McCowan, the time for repentance and the time for rightly teaching and forming the next generations ran out:

She had plenty to say, but her tongue had somehow got glued to her lips. Truly it was now too late. Her will left her. Life withdrawing gathered like a frosty dew on her skin. The last breath blew gently past her nose. The dusty nostrils tingled. She felt a great sneeze coming. There was a roaring; the wind blew through her head once, and a great cotton field bent before it, growing and spreading, the bolls swelling as big as cotton sacks and bursting white as thunder-heads. From a distance, out of the far end of the field, under a sky so blue that it was painful-bright, voices came singing, Joshua fit the battle of Jericho, Jericho, Jericho—Joshua fit the battle of Jericho, and the walls come a-tumbling down (p. 18).

Truly the South did fight in the War, but she fell just as Jericho did. And now the young generations want to abandon the settled, orderly agrarian ethos of their forefathers for city-life, for its fads and trends. Ms McCowan says at one point before her death to her grandson Dick about his fiancée:

“She’ll wrinkle up on you, Son; and the only wrinkles land gets can be smoothed out by the harrow. And she looks sort of puny to me, Son. She’s powerful small in the waist and walks about like she had worms.”

“Gee, Mammy, you’re not jealous are you? That waist is in style” (p. 10).

Just a little later, when discussing a sick cousin who stays at the plantation house, Dick says to his grandmother,

“I was wondering about Cousin George… If I could get somebody to keep him. You see, it will be difficult in the winters. Eva will want to spend the winters in town…” (p. 11)

The New South has become a wretched a place, unrecognizable in many ways to the generations who came before it. As with Dick and his cousin, there is little in the way of self-sacrificing love anymore, and as Miss Elizabeth Madox Roberts shows in her short story ‘The Haunted Palace’, even the Adamic vocation of naming and caring for creatures has been replaced with cruelty towards those living beings:

“Fannie Burt asked me what was the name of the sow or to name what kind or breed she was. ‘Name?’ I says. As if folks would name the food they eat!”

Hubert laughed at the thought of naming the food. Names for the swine, either mother or species, gave him laughter. To write with one’s hand the name of a sow in a book seemed useless labor. Instead of giving her a name he fastened her into a closed pen and gave her all the food he could find. When she was sufficiently fat he stuck her throat with a knife and prepared her body for his own eating (Not by Strange Gods, New York, Viking Press, 1941, pgs. 7-8).

The inhabitants of the New South do not understand and do not value the virtues of their ancestors. This fills them with fear and anger when confronted by them, and they lash out in agony to destroy that which torments them. Miss Roberts again illustrates with Jess, wife of Hubert, who is exploring the fine old plantation house they have come into possession of:

Tall white doors were opened into other great rooms and far back before her a stairway began. She could not comprehend the stair. It lifted, depending from the rail that spread upward like a great ribbon in the air….

When she had thus, in mind, ascended, her eyes closed and a faint sickness went over her, delight mingled with fear and hate. She was afraid of being called upon to know this strange ribbon of ascent that began as a stair with rail and tread and went up into unbelievable heights, step after step. She opened her eyes to look again, ready to reject the wonder as being past all belief and, therefore, having no reality.

“What place is this?” she asked, speaking in anger. Her voice rang through the empty hall, angry words, her own, crying, “What place is this?”

…What she could not bring to her use she wanted to destroy….Before her a long mirror was set into a wall. In it were reflected the boughs of the trees outside against a crisscross of the window opposite.

She was confused after she had looked into the mirror, and she looked about hastily to find the door through which she had come. It was a curious, beautiful, fearful place. She wanted to destroy it….Turning her back on the place, she went quickly out of the doorway.

…A sadness lay heavily upon her because she could not know what people might live in the house, what shapes of women and men might fit into the doorway. She hated her sadness and she turned it into anger (pgs. 26-9).

Such are New South Southrons today, confused and angry as it regards their heritage. And because of this, their longing, like that of Jess and Hubert, has become to defile this heritage:

On a cold day in January when his ewes were about to lamb, Hubert brought them into the large house, driving them up the stone steps at the west front, and he prepared to stable them in the rooms there….

“It was a good place to come to lamb the sheep,” she called to Hubert. “I say, a good place.” She had a delight in seeing that the necessities of lambing polluted the wide halls. “A good place to lamb….” (pgs. 29-30)

But all of these thoughts and actions merely serve to show how monstrous the New South has become:

All at once, looking up suddenly as she walked forward, she saw that an apparition was certainly moving there and that it was coming toward her. It carried something in its upraised hand. There was a dark covering over the head and shoulders that were sunk into the upper darkening gloom. The whole body came forward as a dark thing illuminated by a light the creature carried low at the left side….It came forward slowly and became a threatening figure, a being holding a club and a light in its hands….

As she hurled forward with uplifted stick the other came forward toward her, lunging and threatening. She herself moved faster. The creature’s mouth was open to cry words but no sound came from it.

She dropped the lantern and flung herself upon the approaching figure, and she beat at the creature with her club while it beat at her with identical blows. Herself and the creature were then one. Anger continued, shared, and hurled against a crash of falling glass and plaster. She and the creature had beaten at the mirror from opposite sides.

…Jess stood back from the wreckage to try to understand it. Then slowly she knew that she had broken the great mirror that hung on the rear wall of the room. She took the lamp again into her hand and peered at the breakage on the floor and at the fragments that hung, cracked and crazed, at the sides of the frame.

“God’s own curse on you!” She breathed her oath heavily, backing away from the dust that floated in the air (pgs. 32-3).

Decades beforehand, Miss Roberts has captured the spirit of the ‘woke’ social justice warriors roaming the college campuses and government buildings of today’s Southland who can think of nothing better to do with the physical cultural monuments of their past than wreck them. But like the mirror does for Jess, such actions reveal the truth of their inner nature: It is deformed and ugly, summoning with it the curse of God upon themselves.

II. Rebuilding

But now that Dixie has come to her lowest point, it is possible for her to begin to think about renewal and restoration. We turn again to the short stories of Miss Roberts for this. She points out several features of the Southern inheritance that must be maintained if Dixie’s culture is to remain alive.

The first of these we see in her short stories is singing. Those who can sing the old songs of their fathers are whole people. Patty in ‘I Love My Bonny Bride’ exemplifies this. She is full of life; her nieces and nephews adore her; and her singing is filled with a strange power:

Then Allie asked Patty if she still knew a song about an old gray goose, and she sang one about an Aunt Rodey whose old gray goose was dead. While she sang she looked first like Aunt Rodey who was full of grief and loss over the death of her favorite goose, and later looked like the good old gander who was weeping for the death of his favorite wife. The gander came up into her face and looked out through beady eyes and a long, querulous, stiff bill. Patty laughed and the gander went out of her face, and then she was Patty again, whose eyes were dark gray and bright and whose lips were pink (p. 65).

On the other hand, those who let radios and other gadgets sing songs for them are inhuman, like Jess and Hubert:

She did not sing about the house or the dooryard. Singing came to her from the wooden box that was charged by a small battery. She adjusted the needle of this to a near sending station and let the sound pour over the cabin. Out of the abundant jargon that flowed from the box she did not learn, and before it she did not remember….(‘The Haunted Palace’, p. 9)

Singing, as Miss Roberts makes clear here, is a key to passing on traditions from one generation to the next. Participation in other family rituals is important also, however. In ‘The Betrothed’ we find Rhody and her grandmother taking part in the annual hog butchering in December:

But the work of preparing the food went forward, hurried now, for the cold might any day give way to a warm rain. Rhody and the grandmother were asked to perform together a light part of the labor. They were to search out the dainty bits, sweetbreads and other glands. Two large tubs holding the entrails of the hogs stood outside, near the kitchen door. They worked apart from the others, sitting together beside the tubs. The grandmother would bring the small dainties out of the mass and hold them up so that Rhody might cut them free (p. 199).

Out of these traditions come insights difficult for others to perceive:

…She tore the inner portions about in the tub and passed kinds to Rhody, who took away the dainty with her sharp knife. She seemed to be hovering on the brink of some revelation….

…She seemed to be approaching some matter, to be willing to devise relations between themselves and the hog….

…She would try Rhody’s fortune with the entrails of the hog, she said….(pgs. 199-200)

…“I’ll show you a fortune, your fortune.” The old hands were slow in the offal, but they were quick to find. “I’ll find Kirk for you, here in the tub. See, here. You’ll hear ’im sing and talk sweet right outen this tub. I had my hand on ’im just a little while ago. ‘I’ll show ’im to Rhody,’ I said to myself” (p. 202).

We find the same thing described in ‘I Love My Bonny Bride’:

“An ancient custom,” the uncle Tenny was saying. “A home marriage. Dishes of rice. Sacred wheat. Fecundity rites. Use of fruits or grains, sprinkled over the newly wedded pair or around the nuptial bed. Dangers apprehended. The subjective forebodings often conceived in the form of evil agencies. Demons, ghosts, black magic. All of which gives rise to lucky and unlucky days. Taboo” (p. 79).

Such rites may look silly to the overly rational mind of the Modern Age, but there is a good bit of wisdom to be gained if we look beyond the superstitious outer husks. It is that wisdom that we lose by rejecting the old traditions of our forefathers.

But by throwing away their ancient customs and wisdom, we are also breaking our bond with a larger community that transcends our own little sliver of time. This is the result of a lack of trust in them. Trust, Miss Roberts says, is essential for community. She illustrates this in ‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot’. A maturing boy named Amos ‘Moss’ Beavers has alienated himself from his church and family by associating with some unsavory characters in the town. Afraid that he is going to be punished for some of his misdeeds, he runs away. But when the chance for repentance and trust comes again, he takes it:

Questions of Moss went overhead. Had he been seen? He had been missing all day….Spring weather. How can you expect a boy not to be a boy? “Is it against the law for a boy to buy cigarettes? To have cigarettes in hand?” Mrs. Blount asked.

“Not for the boy, no. There’s no crime fixed on him. The law punishes the man that sells, not the little man that buys.”

The old man began to turn his carriage about….

Moss swiftly assumed his habitual self that had no need for caution. He thought of Viney as watching for him at the gate. His own bed would warm him. He rushed out from hiding and held up his hands toward the slowly moving carriage, asking something. The old man moved swiftly aside in the seat to offer room.

“Well, well, Mossie,” the old man said. The beard blew slightly apart and a kindly mouth was bending about words of tender concern. The vehicle was high and the horse moving slowly away. Moss jumped upward to catch at the handle by which one mounted to the seat. Then a large hand was thrust out and the man was leaning forward. The hand came down to catch at the boy’s hand, and thus he was lifted from the road to the seat in the moving conveyance (pgs. 136-7).

If the New South is going to be welcomed back into the community of her forebears like Moss, however, she will have to show certain virtues that are lacking at the moment: humility, a respect for limits, love. Without them, life is brutish, as we see in ‘Holy Morning’. In this passage, Patty, Sabina, and their grandfather are speaking together about the ways of the world:

“It’s a strange world where such is the way things use. I can hear the dogs come nearer.”

“The foxes kill the rabbits and the birds and the geese, and the hounds kill the foxes.”

“Then people, they kill all kinds, and even the fruit and the kinds that grow in the garden. I once, not a long piece of a while ago, had a sudden sight of a thing while I stuck a knife into a turnip.”

“It was the same as if you killed the turnip with your hand. Or when you shell peas out of a pod they look at you and grin sometimes. Or say, ‘These are my insides that are on the way to make more little pea vines, and you eat all down inside your big gizzard.’ ”

“But mankind is the only one that wars on his own kind. That’s a thing to think about surely.”

“Drives his own sort away and hunts his own down off the face of the earth. Does he, Sabina?”

“Mankind does. The mankind is the only sort that so uses his own. I used to read the papers in the eat-place. Day after day it told about such” (pgs. 167-8).

What is also of primary importance for the healing of the South is the embrace of beauty. This is Miss Roberts’s parting message in her short story collection Not by Strange Gods, so it may also be reckoned as that which she considers most needful for her readers to see. The story ‘Love by the Highway’ opens this way:

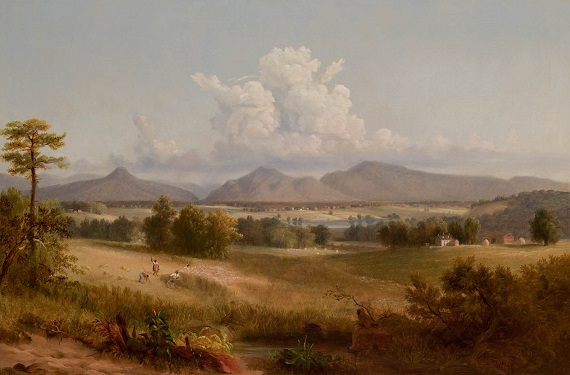

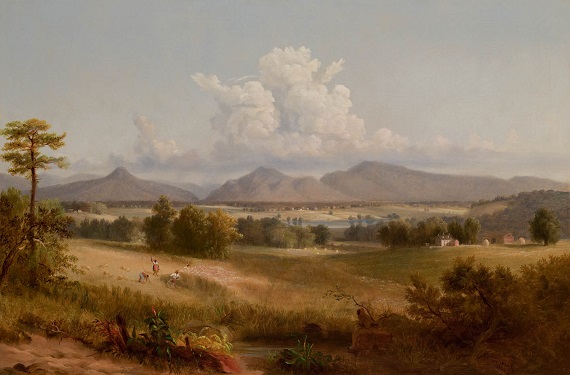

A young woman, Perry Lancer, was digging potatoes in a small field in a mid-morning. Beside the field a highway lifted gently and rounded for the beginning of a slight curve that took it toward the left and out of view. Beyond the potato field were rugged hills, but between these lay an opening through which could be seen a distant valley that was as beauty itself made visible….

Those who walked on the highway often stopped to look at the beauty of the distant vale. But the cars went swiftly about the curve and seldom stopped.

Perry paused in her work once and leaned on her hoe to look at the far beauty that now had the morning light softly shed over it. She always thought that some time she might go there, to walk with the gentle curve of the stream (pgs. 225-6).

Noteworthy right away is who is able to see and appreciate beauty: those who take life slowly – the farmer, the foot-walker, and such like. Those who are in a hurry, those who are much enthralled by technology like motorcars, are unable to see it, much less appreciate it.

Likewise barred from communion with the beautiful are those who are soaked in political ideologies, who believe that their rational minds can solve all of mankind’s problems. These two are represented in the story by Alma Poore and by the schoolhouse, respectively:

Some people were walking on the highway. They went slowly to take the gentle rise, and they looked away toward the lovely vale beyond the rough hills. One of them said:

“I wish I could wait to hear Alma Poore lecture in the schoolhouse. I have to hurry on home and plant the turnip seeds, now the ground is ready, before it might rain.”

“She is a prime hand to talk. And today she, it is said, will tell what’s wrong with the world, and will explain the wars.”

“She’s a power on a platform. The schoolhouse will be filled….”

The voices fell away to broken syllables and they were gone beyond hearing, taking the low hill slowly (p. 228).

Even though these people looked directly at the beautiful vale, they do not seem to see it because they are so caught up in the vanity of their political/ideological pursuits. Perry shows us the better mindset:

Perry dug at another potato hill and left the upturned potatoes on the ground in the sun to dry. She spoke between the irregular rhythms of the hoe:

“And tomorrow I won’t be asking can I give the hens another cup of corn, or can I go to the schoolhouse to hear a learned woman explain the world. I might even, some day, climb on old Zed’s back and ride down through the hills as a crow might fly, and come somehow to the fine out-stretched valley where I have never been except by sight, and where the Woodmans and the Irvines have their fine farms and raise such a good abundance. But it would be more pleasant to go there with some other and not by my lone self” (p. 229).

But in order to gain hold of this greater gift of beauty, some things must be accomplished beforehand. First is gaining the ability to love: We cannot approach the beautiful land if all we honor is the ‘I’ and not the ‘we’: ‘It would be more pleasant to go there with some other and not by my lone self.’

And once again Miss Roberts shows us the power of song – in this case, to make present that which is lacking, as though it were a prayer sung to God:

She sang again, chopping evenly now to lay the tangled weeds away from the potato hills:

The land was made for the living. The sea was made for the dead. My love will come from the highway When the sun is high and red.

None has sent me a letter, And none has given a ring; But love will come by the highway When my heart begins to sing.

Suddenly a swift step was coming near and a shadow was falling over her shoulders. Arms were flung around her, and Perry looked up in one sudden glance before she was gathered into a deep embrace. The new-comer, a man, was kissing her face and laughing over her flying hair and her falling hat (pgs. 229-30).

The newcomer is actually the free-roaming husband of Alma Poore, and in his person Miss Roberts shows us what else we need in order to prepare to receive rightly the gift of beauty: penance. When Perry finds out who he is, when his wife comes to Perry’s house looking for him, she hides him inside where her own dying husband is having prayers read for him and makes him join the men in their prayers:

She took him swiftly over the low floor of the porch and into the dim room beyond. Here an old man, shriveled and gray, was stretched out on a bed, and two other men knelt near the lower bedrail. The kneeling men were reading responsively the Prayer for the Departing Soul. The house was solemn and still. The air inside the room was cool. . . .

The chief reader arose swiftly and thrust his book into Peter’s hands, showing the place. The man making the response droned slowly his “Amen” again, and the first man went hurriedly out at the door, whispering that he had been there since early morning. Peter drew back with a frown of protest, but Perry designated where he was to kneel, and she showed him the place again in the book. He became one of the voices, making the prayer.

…Inside the house were the two voices, one of them Peter Prunt, whose mouth could drip a honey of deceit and lie into a sad woman’s ear. Let him have his due. Let him witness the passing of the old man who had stolen her childhood away. Let him assist with prayer and duty. Let him stay in the dim room through the noon and pray the words out of the book. Justice was to be satisfied (pgs. 241-3).

In this passage Perry shows that one other thing is necessary in our journey toward beauty: a preparation by trials that cleanses us of all befoulment so we will not be burned by the holiness of beauty when we take it into our bosom. Her preparation was this: She had for a long time been the wife of an older man who treated her harshly –

“I waited a long time,” she said, “to be young. First I was a child, and the old man called me his wife in front of people, and smacked me behind the kitchen if the dinner was not enough. Then I was an old woman, tied up in rags, and I counted the eggs and made one off the old man if I could” (p. 227).

III. Beauty, an Indispensable Support

As we have said, beauty was Miss Roberts’s ultimate word to us in parting. It was likewise with another prominent Southerner, Mr William Gilmore Simms, who shortly before his death gave an oration on beauty to the Charleston County Agricultural and Horticultural Society.

Why this strong draw toward the beautiful in the South? Certainly, part of it has to do with the agrarianism at the heart of Southern life. Few folks hewing to Dixie’s old ways would disagree with Prof Vigen Guroian’s comments:

…when Professor Scarry opines that her observation applies to flower gardening but not vegetable gardening, I dissent. I see the point she is making about the practical value of the vegetable garden. “In the flower garden,” she writes, “the plants are grown for their beauty,” whereas in “a vegetable garden the plants are grown for the gardener’s table” (p. 128). Nonetheless, I do not think that this distinction is the heart of the matter. Isn’t the ruby-red Swiss chard as beautiful as any flower? And what is one to make of nurseries that grow annual flowers for commercial purposes?

Not what we garden, but our disposition toward the garden makes gardening just so. For gardening is fundamentally about beauty, whereas farming is about producing. Beauty can exist in the vegetable garden and be appreciated every bit as much as beauty in the perennial bed (The Fragrance of God, Grand Rapids, Mich., Eerdmans, 2006 p. 80).

For just one example of this in traditional Southern life, consider the poem ‘The Cotton Boll’ by Henry Timrod. In the opening section alone, one finds the exact sentiment expressed by Prof Guroian, that beauty is found in every part of the creation. Where today’s Southron farmer might see in cotton only a utilitarian money-making plant, yesterday’s saw something that utterly transcended the mundane:

While I recline

At ease beneath

This immemorial pine,

Small sphere!

(By dusky fingers brought this morning here

And shown with boastful smiles),

I turn thy cloven sheath,

Through which the soft white fibres peer,

That, with their gossamer bands,

Unite, like love, the sea-divided lands,

And slowly, thread by thread,

Draw forth the folded strands,

Than which the trembling line,

By whose frail help yon startled spider fled

Down the tall spear-grass from his swinging bed,

Is scarce more fine;

And as the tangled skein

Unravels in my hands,

Betwixt me and the noonday light,

A veil seems lifted, and for miles and miles

The landscape broadens on my sight,

As, in the little boll, there lurked a spell

Like that which, in the ocean shell,

With mystic sound,

Breaks down the narrow walls that hem us round,

And turns some city lane

Into the restless main,

With all his capes and isles!

But something more is at work. Yes, there was the appreciation of beauty in nature, but it also was manifested in the Old South’s appreciation of order, harmony, and proportion in her architecture, her rhetoric, in the economic system of the plantation that was organized around love and cooperation rather than mistrust and competition.

In other words, there is more to Southern thinking about the subject of beauty than simply enjoyment of and preferment for the outdoors. Deep in his soul, in what the ancients and the Church Fathers call the nous, the ‘ontological receptor’ within man (Mary Naumenko, Restoring the Inner Heart: The Nous in Dostoevsky’s Ridiculous Man, Holy Trinity Publications, Jordanville, New York, 2019, p. vii), the traditional Southerner has been able to perceive the beauty that flows from God Himself (Who is Beauty Itself) more clearly than fellows in other sections of the [u]nited States. This is how one early Church Father, St Dionysius the Areopagite, one of the Apostle Paul’s converts at the Areopagus in Athens (Acts 17:34), describes this Divine Beauty to which Dixie has been so sensitive:

…the superessential Beautiful is called Beauty, on account of the beauty communicated from Itself to all beautiful things, in a manner appropriate to each, and as Cause of the good harmony and brightness of all things which flashes like light to all the beautifying distributions of its fontal ray, and as calling (καλοῦν) all things to Itself (whence also it is called Beauty) (κάλλος), and as collecting all in all to Itself. (And it is called) Beautiful, as (being) at once beautiful and super-beautiful . . . . as Itself, in Itself, with Itself, uniform, always being beautiful, and as having beforehand in Itself pre-eminently the fontal beauty of everything beautiful. For, by the simplex and supernatural nature of all beautiful things, all beauty, and everything p. 41 beautiful, pre-existed uniquely as to Cause. From this Beautiful (comes) being to all existing things,–that each is beautiful in its own proper order; and by reason of the Beautiful are the adaptations of all things, and friendships, and inter-communions, and by the Beautiful all things are made one, and the Beautiful is origin of all things, as a creating Cause, both by moving the whole and holding it together by the love of its own peculiar Beauty; and end of all things, and beloved, as final Cause (for all things exist for the sake of the Beautiful) and exemplary (Cause), because all things are determined according to It (The Divine Names, ch. IV, sec. VII).

Fyodor Dostoevsky has famously said that ‘Beauty will save the world.’ But this salvation is not automatic. For the South or any other people to partake of it, there must be – as Miss Roberts has shown in ‘Love by the Highway’, and as Paul Hamilton Hayne, William Gilmore Simms, many Church Fathers, and some of the ancient Greeks have said – a preparation to receive it through trials and acts of repentance that purify the body and soul, that make it a vessel fit to receive the precious gift of beauty.

If she will do this, then, having received that gift more fully than before, the South will be able to build a better and more enduring society, having in Divine Beauty that which can properly order all her varied and numerous people and institutions, every living thing within her bounds, the works of her hands, all the tragically broken images of her past, and everything in the present and the future, into a harmonious, virtuous, and Grace-filled whole.