Over the years I have known a few—very few—politicians whom I have admired greatly. It seems that the age of those remarkable statesmen and political leaders who once gave substance and guidance to this nation and to our states has passed for good.

Think of it: during the first half century of the existence of the old American Republic we were graced with the likes of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and John Tyler as presidents. In Congress there were such unique worthies as Nathaniel Macon, John Randolph of Roanoke, and John C. Calhoun—Southerners all. And during four years of bitter and destructive war, former Mississippi Senator Jefferson Davis led the destiny of the Confederate States of America.

But since the end of that conflict, I can think of only one American president that I nearly unequivocally admire: Grover Cleveland. Of course, there was Ronald Reagan who is generally venerated by conservatives, although, as in the case of President Trump, his agenda was mostly upended almost from the beginning by Republican Party establishment types who made certain that it did not infringe on their positions or dominance.

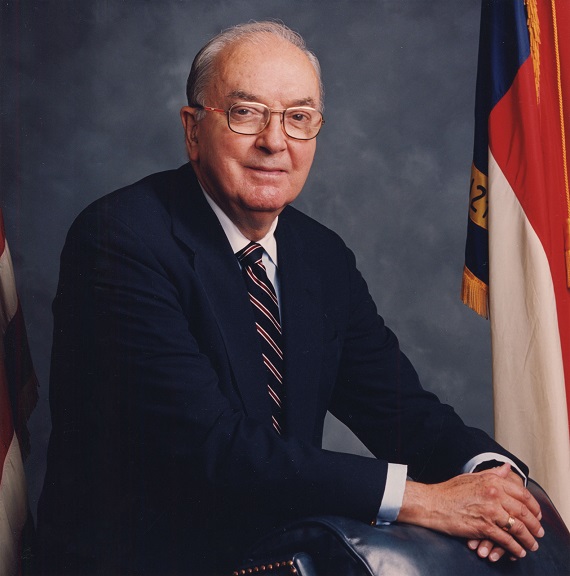

Closer home, here in North Carolina on the state level, the one major political leader that in many ways I “grew up with”—that I have known personally—was the late Senator Jesse Helms. I first got to know him when I was a senior in high school (1965), and he, as vice-president of the Raleigh Rotary Club, helped sponsor me as an overseas exchange student in England. He also featured on one of his televised “Viewpoint” editorials over then conservative WRAL-TV something I also did while in high school: I founded the first “Friends of Rhodesia” student chapter in the world (I was presented a medal by former president of that no-longer existent county, Ian Smith).

Of course, I recognize that even mentioning this will get me labeled in some quarters a “racist” and “white supremacist.” That would be nothing new…and it was not my intent fifty-five years ago; rather it was the realistic understanding I had even as a high schooler that the native population of that former British colony was not ready for self-government and that anarchy and barbarism would occur if majority rule was granted immediately (as it had in so many other former colonial territories, e.g., the Belgian Congo)—and anarchy and barbarism most certainly did eventually occur, with the resultant brutal dictatorship of Robert Mugabe.

Helms stood mostly above the other politicians of his era; he was not afraid to put forward a controversial proposal, even if it meant he would be attacked, even from other Republicans (who consistently caved on essential questions of the day).

Among other political leaders in the Tar Heel State, there was the inimitable State Senator Hamilton Horton who represented for a number of years North Carolina’s Forsyth County (Winston-Salem) in the state General Assembly. Senator Horton was an eloquent, greatly-respected traditional conservative. I actually first got to know him in 1969 when he was a member of the State House of Representatives, and our friendship was renewed when he entered the Senate. I was privileged to work with him closely on the first attempt to enact a Monuments Protection Act. His death in 2006 was a major loss to the Tar Heel State.

I can recount one delightful event in his life in which I was honored to participate. In the mid-1990s I was working at the North Carolina State Archives, and “Ham” (as he was called by friends) telephoned me and asked me to accompany him up to the Buck Spring Plantation in Warren County. Buck Spring had been the seat of the great North Carolina solon, Senator Nathaniel Macon, perhaps the most significant, influential and respected Tar Heel legislator of the nineteenth century whose views on states’ rights and the Constitution profoundly affected such later figures as John C. Calhoun.

Earlier I had completed a massive research project on Macon and Buck Spring; there was talk that it might become a state historic site. After all, Macon had been a national figure of critical importance in American—and Southern—history, the “Father of States Rights.”

But, as they say, “the times, they were a-changing.” By the mid-1990s the idea of state historic site status for Buck Spring had pretty much faded; the rather simple plantation house, itself, was maintained (rather poorly) by the North Carolina Department of Transportation. I had shared a copy of my 500 page report with Ham, and he had taken an interest in Macon (as did Jesse Helms, who entered biographical portions of it into the Congressional Record). And Horton had also heard that the site was not well-maintained.

So, after informing my supervisor that my company was requested, off we went to Warren County along the border with Virginia, which before the War Between the States, as part of the great Roanoke River Valley, had been arguably the most prominent county in the state. From that area of southern Virginia and northern North Carolina men such as Patrick Henry, John Randolph, Macon, and Weldon Edwards had helped shape the destiny of the early American republic.

The “Squire of Buck Spring,” as he was called, had requested that upon his death he be buried on his plantation, and that a pile of small, rounded stones be placed over the grave. When we arrived, we viewed the site in a shambles: most egregiously, Macon’s gravesite was overgrown with poison ivy and poison oak, and an assortment of weeds and new-growth hickory and loblolly pine trees. Ham Horton was appalled, and I recall his words to me: “The DOT is responsible for this site, and I will fix their little red wagon!”

Returning to Raleigh and the General Assembly, Senator Horton almost immediately introduced legislation that would have banned all specialized and vanity license plates for DOT higher ups and would have limited portions of their budgets, pending the cleanup and proper maintenance of Buck Spring. Within a couple of fortnights he telephoned me at home to tell me that the site was now spotlessly cleaned up, and all the weeds on Macon’s grave had been killed and removed! Funny how threatened vanity can work minor miracles!

Hamilton Horton is gone, and there are not many with similar courage and ability like him these days, certainly not in the halls of the General Assembly…or in Washington D.C.