‘The Journalist & The General’

Thomas Morris Chester, the war correspondent in the Eastern Theater for the Philadelphia Press paid homage to General Robert E. Lee on his return from Appomattox and arrival in Richmond, Virginia in 1865. Chester was the only Black American figure to serve in this role for a major newspaper on either side. (1) Chester’s account of the South and Confederates as he moved with the Army of the James was scathing, but his column describing the arrival of Lee into conquered-Richmond in 1865 is notably different. Therein, without any trace of hagiography and/or Lost Cause prose, he wrote with a tone of respect that in the author’s opinion, captured better than any of his contemporaries the simple human heroism of the Gray Fox. The copy Chester wrote reads:

‘Arrival of Lee & Staff – His Reception

The excitement of yesterday was the arrival here of General Lee and his staff, about three o’clock P.M. The chieftain looked fatigued and rode along at a jaded gait. The general with affable dignity received the marks of respect which were manifested by those who happened along the pavement. Several efforts were made to cheer him, which failed, until within a short distance of his residence, previous to which his admirers satisfied themselves with quietly waving their hats and hands, when they were more successful. At his mansion, on Franklin street, where he alighted from his horse, he immediately uncovered his head, thinly covered with silver hairs, as he had done in acknowledgement of the veneration of the people along the streets. There was a general rush of the small crowd to shake hands with him.

During these manifestations not a word was spoken, and when the ceremony was through, the General bowed and ascended his steps. The silence was then broken by a few voices calling for a speech, to which he paid no attention. The General then passed into his house, and the crowd dispersed. The military authorities here will extend every consideration to Lee. Orders will be promulgated affording him and his staff such protection and accommodation as their circumstances may require.’ (2)

This was in itself a noble example of eschewing emotional nationalism to embrace reasoned patriotism, as per George Orwell’s distinction between the two. (3) However, examination of other press coverage reveals a possibility that a mark of respect was subtly paid to the Black Pioneer for this from another newspaper in the Deep South.

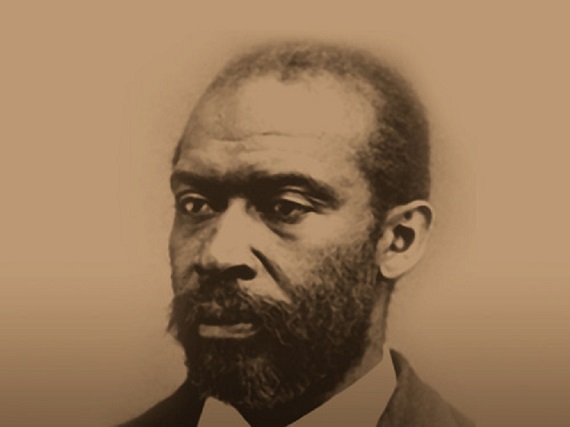

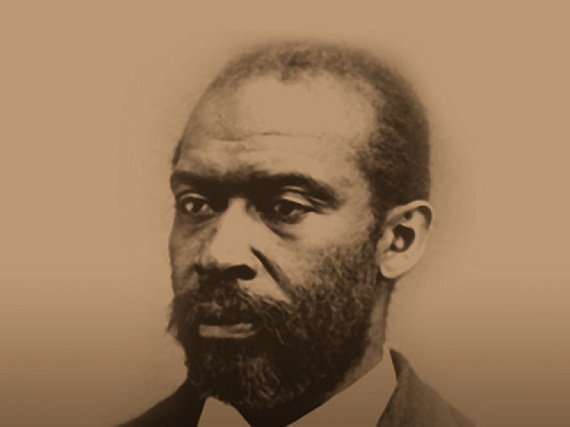

Generally lesser known than other Black American leaders of the era such as Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, Chester led what can only be described as a heroic life himself. A native Pennsylvanian and highly educated, Chester would be involved in such pursuits as travelling and living abroad, Abolitionism, aiding Black colonialisation to Liberia and an serving as an educator for Black Americans and Africans like his contemporary, Martin Delany. Through his life, Chester would also accomplish such things as being among the first Black Americans armed as militia by the state of Pennsylvania. In this capacity, he risked death or capture and being taken into slavery during Lee’s 1863 invasion. His achievements also include becoming the first Black lawyer in England’s and the state of Louisianna’s history, Commander of the Louisisanna state militia and being received and honoured by the Czar of Russia (4) In his landmark capacity as the war correspondent for the Philadelphia Press, it may not be exaggeration to describe his role in documenting the Civil War experience for the United States Coloured Troops’ as akin to that of Charles Bean, the Australian war correspondent of Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, (ANZACs), fame in the First World War. (5) But among these many accomplishments, his tribute to Lee, an adversary through the war, stands out. However, what is not known to date is that by performing this, Chester himself may have been saluted by a Mississippi newspaper, the Meridian Daily Clarion. This reads-

‘Gen. Lee arrived in this city [Richmond] about 3 o’clock Saturday afternoon, attended by five members of his staff. He rode in the city over the pontoon bridge at the foot of the Seventeenth street, and thence up Main street to his residence, on Franklin street, between Seventh and Eighth. Passing rapidly through the city, he was recognized by a few citizens, who raised their hats, a compliment which was in every case returned, but on nearing his residence, the fact of his presence having spread quickly, a great crowd rushed to see him, and set up a loud cheering, to which he replied by simply raising his hat. As he descended from his horse a large number of persons pressed forward and shook hands with him. This ceremony being gotten through with by the General as quickly as possible, he entered into his house and the crowd dispersed.’ (6)

The coverage Chester wrote of Lee’s Richmond-arrival in the copy of the Philadelphia Press is extremely similar to that written in the copy of the Meridian Daily Clarion of the same year. In some aspects, it is nearly identical. Is it possible that the latter copied from the former? Or were these simply different reporters with highly similar writing styles? Is there any connection between them at all? A random comparison of the Lee event to coverage in other newspapers do denote it in similar and synonymous language. (7) However, the language of the Press and Daily Clarion mirror each other more closely and contain information not found in the others. Tom Wheeler, an Abraham Lincoln historian, provides what may be key insight. With the advent of the telegraph, New York newspapers sought to reduce costs’ by forming the Associated Press, whereby, news information would be collected and pooled amongst a high number of press copies. This invariably led to further copying from the resulting publications once set to press. (8)

If Chester’s copy was indeed used to furnish the information of the Mississippi news story, this can not be definitively established, though it is quite possible. And while the argument can’t be made that this was in any way a deliberate or explicit tribute to him, it is nevertheless viable to hold that as an example for setting aside vitriol, and paying homage to General Lee, who by all counts many today would hold intransigently as Chester’s adversary, it is just and satisfying that a newspaper from the Deep South may well have returned a measure of respect to a Black American from the North.

A gratifying mark of reconciliation.

Notes:

(1) Blackett, R.J.M., (Ed.), Thomas Morris Chester: Black Civil War Correspondent, His Dispatches from the Virginia Front, Da Capo Press, 1989, 3.

(2) Philadelphia Press, 16 April 1865.

(3) Refer to the explanation given to distinguish between these two phenomena by Orwell, George, ‘Notes on Nationalism’, first published in the British magazine, Polemic: Magazine of Philosophy, Psychology & Aesthetics, October Ed., 1945.

(4) Blackett, Thomas Morris Chester, ix-xiii, 3-91; Simmons, William J., Turner, Henry McNeal, Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive & Rising, GM Rewell & Company, 1887, 113–117, 671-676. There are many primary and secondary works available upon Martin Delany, such as Frank A. Rollins’, Life & Public Service of Martin Delany, Boston: Lee & Shepard, 1868, which has gone through a number of revisions. However, I am particularly grateful to historian and re-enactor, Timmy Hodge, of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, for his in-depth knowledge of Delany.

(5) Charles Bean’s work documenting World War I by being attached to the ANZAC troops would not only result in his extensive coverage in the press of these ‘Down Under soldiers, but also in his 12-volume, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Bean’s personal papers are collected in the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, Australia, which he also helped to found. Interestingly, the ANZAC allusion boomerangs’ back to America when they are described in the papers of President Herbert Hoover as the “shock troops” of the First World War. See 22 July 1931, Harry Greville-President Hoover, Herbert Hoover Presidential Library, Foreign Affairs’ Correspondence, Australia file. For an overview of Bean, refer to, Ross Coulthart’s, Charles Bean: If People Really Knew; One Man’s Struggle to Report the Great War & Tell the Truth, HarperCollins, 2014.

(6) Meridian Daily Clarion, 7 May 1865.

(7) New York Herald, 18 April 1865; British Columbia Daily Colonist, 24 April 1865.

(8) Wheeler, Tom, Mr. Lincoln’s T-Mails: The Untold Story of how Abraham Lincoln used the Telegraph to Win the Civil War, Harper Collins, 2006, 94-102. I am also grateful to Mz. Teresa Roane, former-head Archivist at the Museum of the Confederacy and present-head Archivist/Historian of the United Daughters’ of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia, and Ranger Matt Atkinson of Gettysburg National Park Service for their critiques and insights into the matter.

* Author’s note: Vancouver Island, from where the British Columbia Daily Colonist was published in the capital city of Victoria, was a separate colony in the British Empire from British Columbia on the mainland until the two were joined in 1866. Nevertheless, the paper was widely distributed and read in both colonies, before and after union.