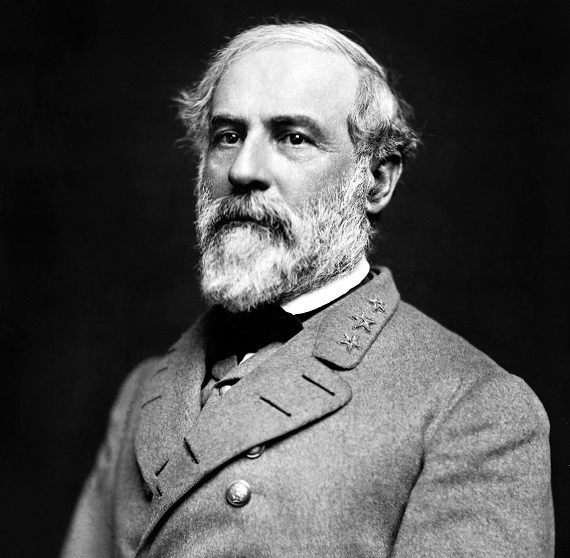

Several years ago, leftist blowhard Richard Cohen at the Washington Post wrote that Robert E. Lee “deserves no honor — no college, no highway, no high school. In the awful war (620,000 dead) that began 150 years ago this month, he fought on the wrong side for the wrong cause. It’s time for Virginia and the South to honor the ones who were right.” He echoed a piece in the New York Times by the equally abrasive “establishment” historian Elizabeth Brown Pryor that portrayed Lee as an abject traitor to his family, a man who was not torn by his decision to side with Virginia and who with equal vigor embraced secession and supported slavery.

A contemporary Internet search for “Robert E. Lee traitor” brings up several articles that lambaste Lee for turning his back on his “country” and violating his military oath. This would not have been the case less than fifty years ago, but Lee has been reduced to a non-American, an insignificant other of American history who had a foot fetish and propagated a “myth” of Southern righteousness. After all, as Cohen wrote, “he offered himself and his sword to the cause of slavery….Such a man cannot be admired.”

Would either say the same thing about Washington or Jefferson, men whom Virginia Royal Governor Dunmore believed were fighting for slavery in 1775? Dunmore “freed the slaves” through a carefully calculated “emancipation proclamation” in the early stages of the American War for Independence. The Continental Congress—replete with non-racist, morally sound and benevolent Yankees—urged Virginia to resist the move. After all, the new American Union was a slaveholding federal republic, and both Washington and Jefferson, along with thousands of other patriots North and South, were either slaveholders or profited from the institution. Did Washington then offer “his sword to the cause of slavery?” No sane historian would advance that position, but these are the bizarre charges leveled against Lee.

Lee represented the best of American society in 1861. He was, like Washington, the quintessential American.

Lee embodied the Jeffersonian model of the early federal republic. This may seem odd. Both his father and most of his kin were ardent Federalists who despised the Jeffersonian Republicans. “Light-Horse” Harry Lee was almost killed by a partisan mob during the War of 1812, and Washington, the model for the Lee household, believed in the necessity of a stronger central government after the States secured their independence from Great Britain in 1783.

But the degree of separation between Washington and Jefferson was slight. Both men considered the English tradition of armed opposition to tyranny born at Runnymede in 1215 to be the guiding principle of self-government. Both were reared in a masculine society dedicated to a rigorous physical, spiritual, and intellectual training of its sons but softened by refinement of manners. Both were agrarians with large estates that rivaled their European counterparts. Jefferson certainly favored a central government with less power than Washington wielded during his second term, but neither man would have raised a hand against Virginia in 1861. Both had descendants who fought for the Confederate cause.

That was still Lee’s Virginia on the eve of war in 1861. Lee was no traitor, and no one among the founding generation would have considered him so. Secession was the American tradition, secured and codified by the Treaty of Paris in 1783 and openly discussed and advanced by both Northern and Southern Founders as early as 1794, a mere five years after the general government under the Constitution was formed. Jefferson called Virginia his “country.” Lee believed the same. His vision of America clashed with Abraham Lincoln’s, particularly in regard to political power, but that does not make it any less American.

Lee’s America, in fact, dominated all levels of society for the first eighty years of American history. An irrefutable case could be made that Lee’s America was the embodiment of the American tradition, born with the first settlers in Jamestown in 1607 and advanced through several generations of independent people. They blazed trails, built farms and businesses, subdued the frontier, secured political liberty, and jealously defended the rights of Englishmen. Was Lee any different?

Not even the worst of the Lee detractors can impale his character. Pryor tried in her Reading the Man, but her accusations fell flat. The charge that he was fighting for slavery also creates the false dichotomy that the North was fighting against it. Even Lincoln did not make that case for most of the War, particularly when it began, but that myth, the “treasury of counterfeit virtue,” still exists. Lincoln’s America is more of a myth than the supposed “Lost Cause” which Cohen scribbled should “get lost.”

Americans who honor Lee as one of the truly great people America has produced recognize, perhaps unconsciously, that Jefferson’s America still has currency.

Perhaps it is fitting that Lee’s birthday falls on the day before another political revolution is set to take place. Donald Trump is certainly no Lee, Washington, or Jefferson, but the people that supported him, the same type of people who formed the backbone of Jefferson’s America, the rock-ribbed “forgotten men” of American society, wait in anticipation for the same type of message the South sent to the general government in 1861. They said no and exercised their right of self-determination.

Lee had the courage of his convictions and selflessly sacrificed his own peace and prosperity for the cause of independence, a government “of the people, by the people, and for the people.” Lee should not be remembered solely as a Southern icon, but like Washington and Jefferson, as an American hero.