. .the South—alone among the civilized communities of the nineteenth century—had hardihood sufficient for an appeal to arms against the iron new order which, a vague instinct whispered to Southerners, was inimical to the sort of humanity they knew.” —Russell Kirk, The Conservative Mind

Certainly those south of the Mason-Dixon line expect little by way of understanding from non-natives, especially from someone born and raised just outside of Detroit, that most Northern of cities. But God loves irony, and He chose to place there one of the South’s strongest defenders. Indeed, perhaps no Northerner has been more sympathetic to the Southern cause this century than has the late Russell Kirk.

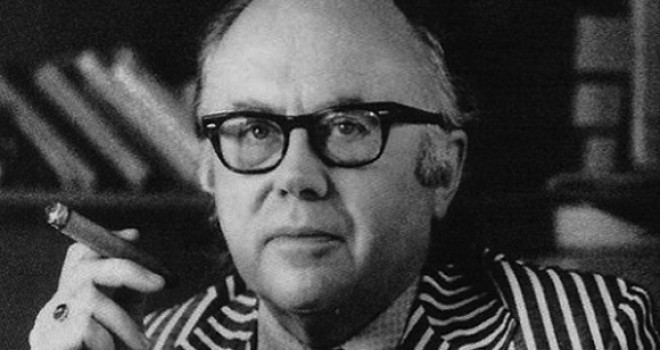

Author of nearly 30 books and hundreds of articles before his untimely death in May, Kirk more than anyone else provided the philosophical underpinnings of the postwar conservative renascence. An original contributor to National Review, Kirk also founded Modern Age and edited The University Bookman for over 30 years. Whittaker Chambers labeled his The Conservative Mind, released in 1953, the most important book of the twentieth century, and throughout Kirk’s writings ran a thread of Southern sympathy and sensibility that did much to shore up Southern conservatism over the past four decades.

Young conservative Russell Kirk, not yet 20 years of age, first encountered an intelligent defense of Southern conservatism when he found the then recently published The Attack on Leviathan by Fugitive and Agrarian Donald Davidson in the new books section of the Michigan State College library. Kirk would later write that “the book was so good that I assumed all intelligent Americans, or almost all, were reading it.” He observed that Davidson’s “regionalism, his social principles, and his literary understanding are equally applicable to every region of this country.” Kirk was sure that the readership of The Attack on Leviathan was in “the hundreds of thousands.” He would later find out the truth from Davidson himself: an unfriendly publicist at the University of North Carolina Press pulped it with only a few hundred copies sold.

To Davidson and his book Kirk would remain loyal. In 1956, the American Scholar asked the then well-known Kirk to choose the most unjustly neglected book of the past few decades. Kirk instantly chose The Attack on Leviathan and sang its praises loudly. Three times he would write about Davidson in his “From the Academy” column in National Review, much increasing awareness of that writer in conservative and national circles. In 1992, Kirk brought out a new edition of The Attack on Leviathan under the title Regionalism and Nationalism in the United States (the book’s original subtitle) under the auspices of his Library of Conservative Thought. M. E. Bradford and publisher J. S. Sanders, recognizing Kirk’s love for Davidson and the South, chose him to write the introduction to Davidson’s second volume of The Tennessee, re-issued in 1992.

In Davidson, Kirk found his Southern counterpart and a man he could revere in much the same way as he revered T.S. Eliot, another of his friends. In his essay “The Poet as Guardian: Donald Davidson,” Kirk wrote that Davidson was “the champion of humane studies against the vocationalism and specialization of our age.” All this about the man he hailed as “the most Southern of Southerners.” Kirk and Davidson, both Christian men of letters, represent a dying breed. Both wrote fine histories and stinging social criticism and though Kirk did not himself write poetry, it is to poetry that he often looked for guidance.

After finishing his undergraduate degree at Michigan State, Kirk attended Duke University which was still a Southern institution in more than name. While in North Carolina, Russell Kirk learned of the South and its ways first hand. Of his time there he wrote (in this third-person autobiographical style): “Kirk had found in the South a conservative society that had been struck a fearful blow 80 years before, and still sometimes seemed dazed by that stroke; but he liked its life far better than the life of Detroit. In the South, then and later, he learned that some of the more oppressive ‘problems’ in life never are solved, unless by time and Providence. He read deeply about the South ‘befo’ de wah,’ and poked into its ashes. In Richmond and Charleston he found communities that had not surrendered unconditionally to the new order of American life.”

Kirk decided to write his master’s thesis on John Randolph, the man he called “the most singular great man in American history.” That manuscript became his first book a decade later. Though Kirk is better known for his discipleship of 18th century English statesman Edmund Burke, it was Randolph, the “American Burke,” whom Kirk discovered first. And it was Randolph of whom Kirk wrote more lovingly and personally. John Randolph of Roanoke is canonical for anyone who would hope to understand the conservative heritage of the South.

Kirk first encountered Randolph while in high school and was “much taken, at the age of sixteen, by Randolph’s freedom from cant and pretence.” In Randolph, Kirk found the proper blend of John Adams’s skepticism of equality and Thomas Jefferson’s belief in a decentralized government. Those views are at the core of the Russell Kirk brand of conservatism, views held as tradition only in the South.

About Randolph, Kirk wrote “Though the course of his life was as fantastic as any romantic novel, the great merit of Randolph’s political utterance is his merciless realism. For cant and slogan he reserved his most overwhelming scorn. Never equivocating, he spoke with a corrosive power unequaled in the history of American politics. In this time when the United States no longer can avoid hard and irrevocable decisions, the imaginative candor of John Randolph or Roanoke deserves rescue from obscurity.”

As with his devotion to Davidson, Kirk was also devoted to John Randolph and sought to rescue him for obscurity. He saw John Randolph of Roanoke through three editions and three different publishers. Kirk also chose the Collected Letters of John Randolph to John Brockenbrough, 1812-1833 as the first book issued through his Library of Conservative Thought from Transaction Books.

Kirk’s best overall discussion of the conservative heritage of the South can be found in The Conservative Mind. In his chapter “Southern Conservatism: Randolph and Calhoun” Kirk both distills his previous writing on Randolph and expands it. Here he places Randolph more in the context of Southern conservatism as a whole and also provides one of the better discussions of John C. Calhoun’s political theories.

Kirk assessed the value of Calhoun’s contribution thus: “The concurrent majority itself; representation of citizens by section and interest, rather than by pure numbers; the realization that liberty is a product of civilization and a reward of virtue, not an abstract right; the acute distinction between moral equality and equality of condition; the linking of liberty and progress; the strong protest against domination by class or region, under the guise of numerical majority—these concepts, provocative of thought and capable of modern application, give Calhoun a place beside John Adams as one of the two most eminent American political writers. Calhoun demonstrated that conservatism can project as well as complain.”

Kirk concluded his discussion of Randolph and Calhoun with the following words: “. . .they deserve to be remembered, these devoted Southern leaders—Randolph for the quality of his imagination, Calhoun for the sternness of his logic. They illustrate the truth that conservatism is something deeper than mere defense of shares and dividends, something nobler than mere dread of what is new; their arguments, and even their failure, reveal how intricately linked are economic change, state policy and the fragile tissues of social tranquility.” Surely no one has explained more accurately for what Randolph and Calhoun and inevitably the South stand.

Calhoun also has found himself the object of Kirk’s loyalties. In 1989 he ably defended Calhoun from John Niven’s biography, and in 1992 he issued Clyde Wilson’s The Essential Calhoun as part of the Library of Conservative Thought. In that book’s foreword Kirk wrote: “In one aspect, Calhoun was the voice of what Henry Adams called ‘the sable genius of the South.’ In another aspect, Calhoun was the best exponent of the idea of political order that underlies both the written constitution and the unwritten constitution of the American Republic.” If Toryism indeed is loyalty to individuals, Russell Kirk easily qualified.

In 1958, Kirk devoted an entire issue of his journal Modern Age to the South and contributed an essay extolling the region’s virtues and value. In “Norms, Conventions, and the South,” his most aggressive defense of the South, Kirk sounded like a man from Macon, Charleston or Lexington. Here he defended the inherent conservatism of the region against the radical and liberal leveller. He praised the South’s adherence and defense to norms and conventions handed down by tradition and divine revelation. Wrote Kirk, “The South, then, has been the Permanence of America: the defender—sometimes consciously, sometimes blindly—of principles immensely ancient, of conventions that yet have meaning. . .The convictions and customs of the South perpetually irritate the radical reformer, who is impatient to sweep away every obstacle to the coming of his standardized, regulated, mechanized, unified world, purged of faith, variety and ancient longings. . .Without the South to act as its Permanence, the American Republic would be perilously out of joint. And the South need feel no shame for its defense of beliefs that were not concocted yesterday.”

It truly was the good fortune of the region to have such an able defender. A man, it seemed, who was born out of place. Until his death at the age of 75, Kirk lived in the Michigan backwoods in his ancestral village of Mecosta, far from the maddening crowd of Detroit. In “Dancing Man,” a review of Andrew Lytle’s From Eden to Babylon, Kirk quoted approvingly Lytle’s view that the American backwoods “is the one feature, along with pioneering, that is common to the different sections of this no longer commonly minded country.” For almost 40 years Kirk lived there, writing, entertaining, reading Sir Walter Scott and planting trees. Living a quiet life detesting the bustle of urban industrialization, he was styled a Northern Agrarian. Like the Twelve Southerners, Kirk believed in the land, the community and ethical labor. He knew that the good things in life are family, friends, conversation, good food and good work.

Kirk’s Southern temperament is well explained by Kirk himself. In writing about Davidson’s Leviathan, Kirk penned “I am a Northerner of Northerners. But what survives of the old life of Michigan and what remains of the old ways of Tennessee, stand allied against the grim gray uniform domination of the Utopian centraliz-ers—the dreary present and future which Mr. Davidson symbolizes as ‘the Long Street.'” In “The Dogma of the South,” Kirk wrote approvingly of John Donald Eade’s concept of a South that is neither geographic nor physical but that still stands against “the quick demons of disintegration and chaos, active throughout Western civilization.” It is of that South that Russell Kirk found himself an honored citizen.