History is remembered as a narrative, not facts and figures. If the story is told from the viewpoint of past sins, the rendering condemns our ancestors and makes us ashamed of our legacy. If it is told from the viewpoint of ancestral virtues, it leaves us proud of our tradition and inspired to build upon the accomplishments of those who came before us.

Thus, if Civil War history is told from the perspective of slavery, white Southerners are portrayed as America’s evil twin and Confederate statues are torn down. But when the virtues of the Confederate soldier were considered, the narrative inspired—and can continue to inspire—future generations of all Americans.

Consider, for example, General Robert E. Lee. He took responsibility for his army’s failures at Gettysburg. In contrast, then and now many leaders seek to blame others for their failures as Hillary Clinton repeatedly demonstrates. Moreover, Lee took responsibility immediately. He went forth to meet the Confederate infantry retreating from Pickett’s failed charge telling them “. . . all this is my fault; it is I who has lost this fight and you must help me out as best you can. . .This will all come out right in the end, but you all must rally and we will talk it over afterward. We want every good man now.” Although modern historians like to disparage Lee, they cannot deny that he was probably more beloved and respected by the men who served under him than any other general in Gray or Blue.

Retired Army Officer, best-selling Civil War author, TV news commentator, and Northerner Ralph Peters, had this to say about the typical Confederate soldier:

The myth of Johnny Reb, the greatest of infantrymen, happens to be true. Not only the courage and combat skill, but the sheer endurance of the Confederate foot soldier may have been equalled in a few other armies over the millennia, but none could claim the least superiority. Especially (but not only) in the Army of Northern Virginia, the physical toughness, fighting ability and raw determination of those men remains astonishing.

Billy Yank showed plenty of courage, too, and yes, the Southern armies had their share of shirkers and deserters, but the fact that most Johnnies fought on against crushing odds, hungry, louse-infested and flea-bitten, clothed in rags and exposed to the elements, often sick and usually emaciated . . . the more I study those men, the more I admire them.

As noted in an earlier post the legacy of the Confederate soldier inspired warriors in every American war since the 1898 fight to free Cuba. Three of the most decorated soldiers of World Wars One and Two and the Vietnam War were white Southerners born into grinding poverty. As boys they hunted game for food, not sport. During World War Two, the first American flag to fly over the captured Japanese fortress at Okinawa was a Confederate Battle Flag. It was put there by a group of marines to honor their company commander—a South Carolinian physically disabled by a wound in the victorious assault. Some of the tank crews that freed prisoners from German concentration camps also flew the Confederate Battle Flag.

Such veterans vouchsafed for us the country we have today. It is the World’s wealthiest and our culture has more worldwide influence than any other. It is a country for which aliens will flagrantly violate our immigration laws in exchange for a chance to live here. It is a multicultural society, but one so fair that it elected Obama as President even though he identifies with the black race that represents merely thirteen percent of our population. It is one where women represent the majority of college graduates and have more opportunities than in any other country in the World.

Yet America is also a country in which most academics and their acolytes primarily see flaws. Consequently, they espouse a false victimhood ideology that despises white males—especially Southerners—while portraying all minorities and women (a majority) as victims. These critics imagine only the worst of those who disagree with them and increasingly demand that contrary voices be censored. Instead of meeting conflicting opinions with arguments, they respond with ad hominem code word accusations intended to end all discussion in the manner of a trump card. Examples include “racist,” “homophobe,” “misogynist,” and “Lost Causer.” Predictably, the white Southern male is hated most because his critics consider him to be all four.

To be sure, racism lasted a long time in the South. But it was not as the typical academic imagines it to have been. Southern men like Mockingbird’s fictional Atticus Finch really existed. While such men lived in a time and place where most blacks were presumed to be destined to become members of a perpetual servant class, they did not hate blacks. Some brave ones even felt that blacks merited protection against other whites who were even more racist. And they acted upon those feelings.

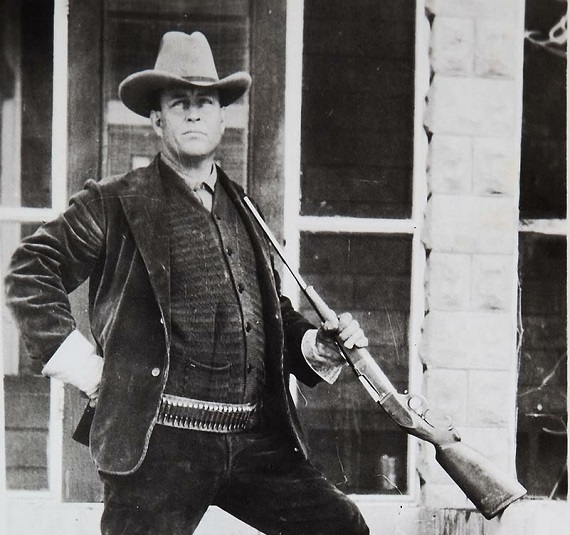

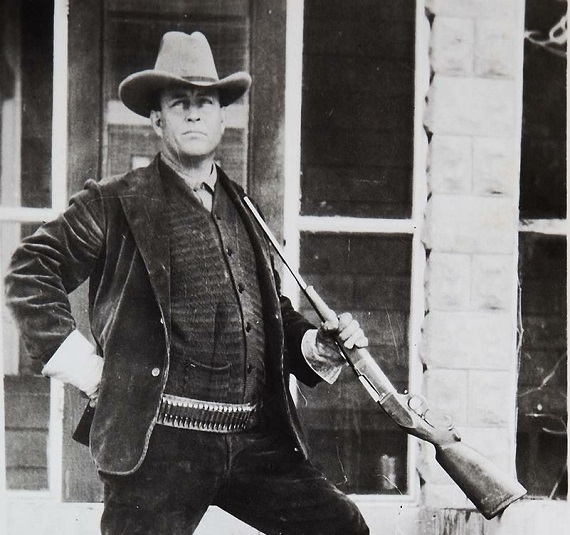

One example was Frank Hamer. He was the Texas Ranger who led the group of lawmen that put an end to Bonnie & Clyde. Hamer began his career in 1905 on horseback and fought most every kind of outlaw until about 1940. Although his racial attitudes were like most Texans of the era, he faced down lynch mobs when they wanted to string-up blacks without a trial. Even though the rescued men were most likely guilty he risked his own life to insure that they got due legal process. Such is the ambiguity of the Southerner from that era. When pondered honestly, it mystifies the typical modern historian. Unfortunately, they seldom ponder it at all and are blind to the nuance of Southern race relations in the years before the historians were educated indoctrinated.

Thus results today’s dominant narrative of the South. It is fabricated upon a foundation of legendary sins instead of genuine historical virtues.