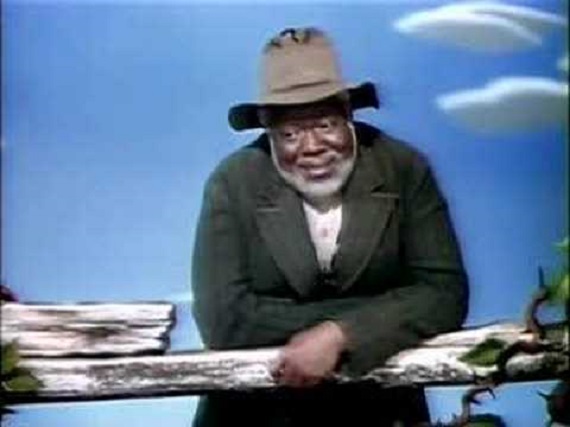

Most of us, even the youngest, have heard of the magnificent Disney film, “Song of the South,” originally released in 1946. And certainly we are familiar with its hit song, “Zip-a Dee Doo Dah.” Some of us have seen this partially animated classic, or recall seeing it years ago, even though it is officially unavailable at present. Disney refuses to release it to the American market.

Well, superbly reproduced video copies can now be purchased in the United States.

Here’s the rest of the story.

In our politically-correct times, various films—mostly dating from the 1940s and 1950s—that are genuine cultural treasures have been or are in danger of being banned or removed de facto from public view. In particular, it has been classic films about the South and the Confederacy which have become increasingly the most notable targets of fierce and unhinged attacks, objects of efforts not only to eradicate wonderful cinematic works of art, but extinguish their very memory and the memories they convey.

It’s a campaign that parallels the frenetic attempt to remove monuments honoring Confederate veterans, and now has expanded to censor and ban artwork and memorials to such national figures as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson or Christopher Columbus. And that movement only increases and broadens its targets as time passes.

It is, of course, part and parcel of the multifaceted and ongoing campaign in our society, in fact in all of the remnants of Western Christian society (including Europe) to efface any symbol of our historic cultural heritage.

It is all about the progressivist template which posits that “race” is the central motivating factor in history. All else pales in significance and importance: not religious belief, not shared cultural heritage, not a common history or language, but race is the determinant for practically everything in society. The historic “colonialized” peoples, black and brown (but curiously normally not Asians), according to this narrative, are a downtrodden underclass, oppressed historically by the European white patriarchy who have brutally amassed their fortunes and power at the expense of those black and brown peoples.

Thus, according to such Marxist ideologues as Frantz Fanon (in his influential volume, The Wretched of the Earth, 1961) and Saul Alinsky (in his handbook for modern revolutionaries, Rules for Radicals, 1971), those races must overthrow the white European hierarchy, by whatever means necessary.

It is not even a question of the overused totem word “equality.” For these newer revolutionaries, although they may use that term widely (and indiscriminately), actually desire a new form of inequality, with themselves at the top of the mound heap—witness the politically enhanced campaign for “reparations,” now adopted in some form by most Democratic candidates for president.

This template of race and liberation from racism is an explosive theorization that inevitably produces violence and social upheaval. And it fits into a Neo-Marxist revolutionary narrative which employs it as a means to power. Indeed, one may question whether these new fanatical revolutionaries’ professed concern for the underclass is really that, or rather, a classic Marxist use of the “proles” to advance their replacement of one oligarchy with another of their own making.

Interestingly, for those millions of radicalized “woke” white millennials (and craven politicians who cower in fear at their latest barbarity), this meme has become a kind of exercise in public expiation of their own sense of “white guilt,” pounded into them by poisonous academic and cultural elites who dominate our society and our educational system.

Like most revolutionary movements, in the arts and literature it initially appeared modest in its goals: “We just want to restrict the most offensive [for minorities] works of art,” it declared, “such books as Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn or Helen Bannerman’s The Story of Little Black Sambo, which are perceived to be racist.” Or, “we just want to ban such songs, like ‘Dixie,’ that produce discomfort or instill fear into minorities.”

But, of course, like any revolutionary movement, book burning takes on a life and logic of its own. And its list of targets has grown as the cowardice and corruption of the supposed opposition to it has collapsed.

This is perhaps most noticeable in the fate of classic films that portray the Old South or Confederacy in a favorable light. Such works fail to satisfy the correct propaganda purposes and, thus, do not further the revolution.

Back in 1956 as a young boy my family and I went to see a special, tenth anniversary screening of Disney’s masterful semi-animated film, “Song of the South.” I can still remember the wonderful sensation, the delightful songs, the humor and imagination, and the heartwarming story. This cinematic epic is a monumental film, a true American classic with appeal to viewers of all ages, with a message of loyalty and genuine love that transcend both the times and race.

It is about and takes place in the Old South, on a Southern plantation, one in which a familiar and peaceful–albeit unequal–relationship between white and black Southerners ensures a good story. But for our modern custodians of good taste and artistic virtue, this is a very big problem: “Song of the South” does not call for a race war, nor does it demonize Southerners or the Old South. Thus, today this cinematic masterpiece, comparable at the very least to anything else Disney produced (e.g., Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Fantasia, etc.) is not commercially—officially—available in the United States.

And you know the reason: our cultural elitists and politically-correct “woke” cultural masters inform us that it’s “racist.”

Walt Disney passed from the scene in 1966, and his company soon fell under the control of New York cosmopolitans (e.g., Michael Eisner and Bob Iger) whose appreciation of traditional American heritage and traditions was about as great as their appreciation of Eastern North Carolina barbecue.

In other words, given the changing cultural and political climate in the United States, releasing “Song of the South” for American distribution was not something they were going to do (even with the potential millions of shekels they might amass).

Here is what the Wikipedia tells us:

“The Walt Disney Company has yet to release a complete version of the film in the United States on home video given the film’s controversial reputation…. From 1984-2005, Disney CEO Michael Eisner stated that the film would never receive a home video release in the U.S.A., due to not wanting to have to hire a viewing disclaimer. However he favored its release in Europe and Asia where “slavery is a lesser controversial subject”.… In March 2010, new Disney CEO Bob Iger stated that there are currently no plans at this time to release the movie on DVD yet, calling the film “antiquated” and “fairly offensive”…. Film critic Roger Ebert, who normally disdained any attempt to keep films from any audience, supported the non-release position, claiming that most Disney films become a part of the consciousness of American children, who take films more literally than do adults…. The full-length film has been released in its entirety on VHS and LaserDisc in various European and Asian countries. In the UK, it was released on [the European, non-American video format] PAL VHS first in 1983, then in 1991, 1992, and 1996, and again in 2000. In Japan it appeared on NTSC [American format] VHS, and LaserDisc in 1990 with Japanese subtitles during the songs (additionally, under Japanese copyright law, the film is now in the public domain). An NTSC DVD was released in Taiwan for the rental market by “”Classic Reels”.”

Even in England it is now listed by Amazon.co.uk as “no longer available” and extremely difficult to find. My first copy came from Taiwan, replete with Taiwanese subtitles that I could not, unfortunately, shut off.

Even in England it is now listed by Amazon.co.uk as “no longer available” and extremely difficult to find. My first copy came from Taiwan, replete with Taiwanese subtitles that I could not, unfortunately, shut off.

There have been private copies circulating, and over the years I’ve purchased several of them, with varying degrees of success as to film reproduction quality, color, and sound.

But now, just recently I discovered an American source for an excellent video reproduction of the film, in glorious Technicolor and, even more attractive, at an excellent price. I recommend it without hesitation.

The quality of the video reproduction is superb in every way, color, sound, contrast, sharpness. And the price (INCLUDING FIRST CLASS POSTAGE AND HANDLING) is only $11.99. Additionally, this seller will include a second and largely forgotten Disney classic, “So Dear to My Heart” (1948), as a second DVD, for only $16.99 for both. I ordered my copies on a Saturday, and the order came priority mail the next Tuesday, that is, in record time, in a nice DVD package with cover art.

In short, this is a self-recommending purchase, and an opportunity to fully appreciate, enjoy, and participate in the richness of our cinematic cultural inheritance.

Given the unhinged and frenetic attempts to censor and eradicate our heritage, I don’t know for how long this fine copy of an American and Southern classic will be available before the PC police denounce the site and demand it cease offering copies to purchasers.

As for me, I plan to get several additional copies for my own archive and for possible Christmas gifts.

And my advice is for you to do the same.

Where can one order this copy of “Song of the South”? Thank you!

“The quality of the video reproduction is superb in every way, color, sound, contrast, sharpness. And the price (INCLUDING FIRST CLASS POSTAGE AND HANDLING) is only $11.99. Additionally, this seller will include a second and largely forgotten Disney classic, “So Dear to My Heart” (1948), as a second DVD, for only $16.99 for both. I ordered my copies on a Saturday, and the order came priority mail the next Tuesday, that is, in record time, in a nice DVD package with cover art.”

You can watch Song of the South here.

https://archive.org/details/SongoftheSouth1080pRestoration