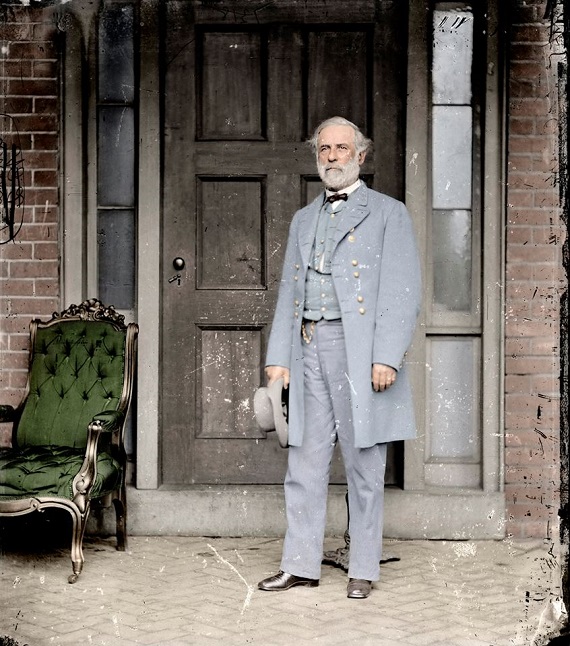

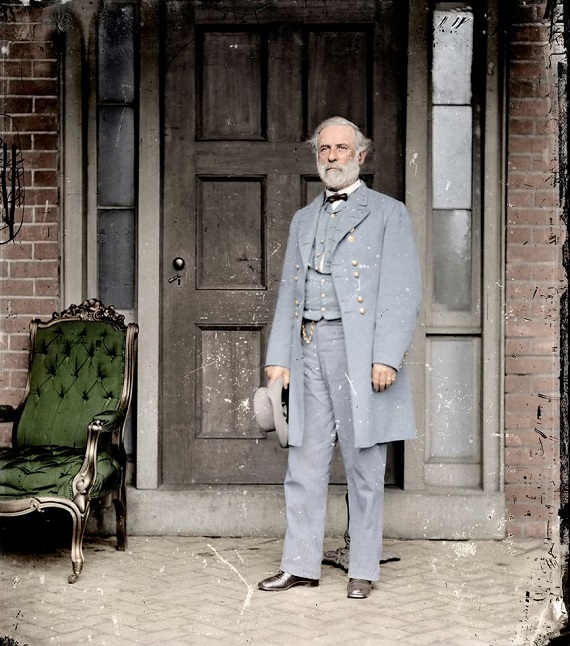

To those Americans who revere him—sadly, a dwindling number these days—Robert E. Lee is still much a “Marble Man”: the noble face of the antebellum South, the tragic embodiment of the Lost Cause, the “perfect” man, as a contemporary deemed him. Even his admirers are unaware of the some of the more interesting details of the life of this very human hero. Here are ten facts about Robert E. Lee that you may not know…

1. He did not grow his famous beard until late in life. As a young man, Lee wore long sideburns; later, he would sport only a mustache. A fellow cadet at West Point said that Lee’s “personal appearance surpassed in manly beauty that of any other cadet in the corps.” Until he grew a beard during the winter of 1861-1862, Lee had always appeared younger than his years. The white whiskers made him look older, as did the onset of heart disease and the stress of commanding an army during the war of brother against brother.

2. He was largely responsible for opening up the Mississippi River to navigation. As an Army engineer in the 1830s, Lee was stationed in St. Louis and, working with the forces of the river, directed the improvement of the channels of the Mississippi so as to improve greatly its navigability. And Lee, who always shared as much as possible in the hardships of those he commanded, was not reluctant to get his own hands dirty. “He went in person with the hands every morning about sunrise,” an observer recalled, and worked day by day in the hot, broiling sun…. He shared in the hard task and common fare and rations furnished to the common laborers—eating at the same table.”

3. He was extremely frugal with money. The father he had barely known, Light Horse Harry Lee, one of the heroes of the American Revolution, was a spendthrift and a poor businessman, who had whittled away the Lee estate. Lee had heard enough stories about his father, and had seen enough of the effects of his spending habits on his mother, that he adopted an attitude of extreme frugality and careful accounting with money. On one occasion, he wrote to his bank about a discrepancy of $1.20 in his account balance of $841.77. In marrying Mary Custis, a descendant of George Washington, he inherited another mismanaged estate, that of Arlington House, which was in disarray and disrepair. He worked diligently for several years to return Arlington to profitability. Lee was also careful to pay all his debts, once during the war even sending money across the lines to pay a blacksmith $2 that he owed him.

4. He corresponded with Whistler’s mother. While Lee was Superintendent of the Military Academy at West Point, young James McNeill Whistler was a cadet—and a very poor one at that. Though Lee was ultimately compelled to expel from the school the “moody and insolent” Whistler when he failed his chemistry class (“If silicon were a gas I would have been a major general some day,” Whistler cheekily said later), Lee took a sincere interest in the boy, as he always did with those under his care. He wrote several letters to Whistler’s mother, emphasizing the need for the boy to be diligent in his efforts, and updating her on her son’s health. After leaving the Academy, Whistler, of course, became a famous artist, painting in 1871 the portrait that became known as “Whistler’s Mother.”

5. He loved to flirt: Though by all accounts an unfailingly faithful husband, Lee delighted in the company of pretty, young women, even regaling his wife about encounters with other members of the fairer sex. “How I did strut along…. How you would have triumphed in my happiness,” he blithely wrote to his wife Mary after he had the opportunity to entertain the lovely Harriett Talcott, who was an object of Lee’s special attention. By all contemporary accounts and portraits, Lee’s wife was a plain, if not homely, woman, and perhaps this fact spurred Lee to conquer the hearts of more attractive women. Pretty girls, Lee told a friend, made his heart “open to them, like a flower to the sun.”

6. He slept in a modest soldier’s tent and ate the same rations as his men. Much to the chagrin of his staff, Lee almost always turned away delicacies offered by the wealthier civilians in the area where his army camped. When fresh fruits or vegetables, fine meat, good bread, or even quality spirits were sent to his headquarters, Lee would write a gracious letter of thanks to the benefactor and quietly send the food onto his men, usually the wounded in hospital. Lee always ate simple meals and took the typical army ration given to his men. Similarly, he routinely turned down offers to use the homes of Southerners as his headquarters, preferring to sleep outside in his modest tent, which, incidentally, was that of a New Jersey officer captured by the Confederates. He thus made it a point to share the daily hardships of his men as much as possible, and to know them as much as he could. Once, as Lee was returning to his tent, he noticed a soldier peeking inside. “Walk in, Captain,” Lee called out, “I am glad to see you.” The startled soldier turned and addressed Lee: “I ain’t no captain, General Lee. I’s just a private in the Ninth Virginia Cavalry.” “Well, come on in, sir,” Lee responded. “If you aren’t a captain, you ought to be.”

7. He rode other horses besides Traveller during the Civil War. Though the iron-gray Traveller may be the most famous horse in American history, Lee rode other horses during the conflict. According to the website of Stratford Hall:

“When Lee purchased Traveller, his stable already contained two horses, Richmond and Brown-Roan: Richmond, a bay stallion, was acquired by General Lee in early 1861. The General rode Richmond when he inspected the Richmond defenses. Richmond died in 1862 after the battle of Malvern Hill. Brown-Roan was purchased by Lee in West Virginia during the first summer of the war. Also referred to as ‘The Roan,’ the horse went blind in 1862 and had to be retired. He was left with a farmer.

Two other horses, Lucy Long and Ajax, joined Lee’s stable after he purchased Traveller: Lucy Long, a mare, served as the primary backup horse to Traveller. Lucy Long remained with the Lee family after the war. Outliving General Lee, she died when she was thirty-three years old. Ajax, a sorrel horse, was used infrequently because he was too large for Lee to ride comfortably. Ajax also remained with the Lees after the war. He killed himself in the mid-1860s by accidentally running into an iron gate-latch prong.”

8. He disliked slavery and abhorred secession. Though Lee never personally owned slaves, he was charged with managing for a five-year period the 200 slaves at Arlington Plantation who had belonged to his father-in-law after George Washington Parke Custis’ death; Lee was a stern taskmaster in regard to the Arlington slaves, who had been used to the lax standards of their late owner, and perhaps once Lee had three runaway slaves whipped. Lee certainly believed the white race to be superior to the black, once observing “that wherever you find the negro, everything is going down around him, and wherever you find a white man, you see everything around him improving.” And yet, in a letter of 1858, Lee deemed slavery to be “a moral and political evil in any country,” and once emancipation came, he accepted the new social realities and encouraged other Southerners to do so also, treating freed blacks with respect; on one occasion, he was the first to join a black man who had dared to kneel first, ahead of white worshippers, at the communion rail at Lee’s Episcopal parish in Richmond.

If Lee found slavery distasteful, he positively detested secession. In a letter of January 1861 to his son Custis, Lee wrote:

As an American citizen I take great pride in my country, her prosperity & institutions & would defend any State if her rights were invaded. But I can anticipate no greater calamity for the country than a dissolution of the Union. It would be an accumulation of all the evils we complain of, & I am willing to sacrifice every thing but honour for its preservation. I hope therefore that all Constitutional means will be exhausted, before there is a resort to force. Secession is nothing but revolution. The framers of our Constitution never exhausted so much labour, wisdom & forbearance in its formation & surrounded it with so many guards & securities, if it was intended to be broken by every member of the confederacy at will. It was intended for pepetual [sic] union, so expressed in the preamble, & for the establishment of a government, not a compact, which can only be dissolved by revolution or the consent of all the people in convention assembled.

Lee often railed against Southern “Fire-Eaters,” who fanned the winds of war in their eager desire for the South to form its own confederacy, ultimately blaming them and extremist Northern abolitionists for the bloody conflict. And yet, Lee, after much agonizing, determined that his duty lay in remaining loyal to his country—that is, his native State of Virginia. He told a cousin in the federal army:

“I have been unable to make up my mind to raise my hand against my native state, my relations, my children & my home . . . & never desire again to draw my sword save in defence of my State. I consider it useless to go into the reasons that influenced me. I can give no advice. I merely tell you what I have done that you may do better.”

9. He met Ulysses S. Grant a second time at Appomattox after the famous surrender. The day after the famous meeting at the McLean House, Lee and Grant, who had served together in the Mexican War before becoming adversaries in the War Between the States, met on a knoll between the two armies. Grant tried to convince Lee, who until the day before had been the commander of all Confederate armed forces, to use his stature to persuade the remaining Confederate forces to surrender. Lee demurred, saying that such a course would now be improper for him to take. “I knew,” Grant recalled, “there was no use to urge him to do anything against his ideas of what was right.” Later, when Lee was indicted for treason by a federal grand jury, with the threat of arrest and possible execution hanging over him, he appealed to Grant, noting that the terms of his army’s surrender included the stipulation—drafted by Grant himself—that “each officer and man will be allowed to return to his home, not to be disturbed by United States authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside.” Grant concurred with Lee’s interpretation and urged Lee to apply for a federal pardon, which Grant said he would endorse. Lee did so, sending the documents to Grant, who indeed forwarded them on to President Andrew Johnson with his endorsement. (The application would be “lost,” and Lee’s citizenship would not be restored until 1975—but that is another story.) What Lee did not know was that Grant quietly let it be known that he would resign from the army if Lee were to be arrested.

10. He turned down many lucrative business offers after the war ended. The Lees’ Arlington estate had been seized by Union forces before war’s end, and after Appomattox, he returned to a modest house in Richmond that he had rented for his wife and family. With his legal status an open question, and his financial resources much reduced, Lee looked for a way to make a living and to contribute to society. “Lee turned down every invitation to prosper by his name,” Ernest B. Furguson writes: “to be president of the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway; to command the Romanian army; to be governor of Virginia; to write his memoirs—or merely sign them written by someone else; to be president of insurance companies; to move into an English manor house with an annual stipend.” Lee at last found a position that suited him: the presidency of Washington College in Lexington, where he would earn $1,500 a year, plus a percentage of the total tuition payments the college received. Lee revitalized the dying institution, building it into a university by adding practical courses in modern languages (including one of the very few Spanish programs in the country), engineering, commerce, farming, and the law to the existing program of classical education. He also opened the first-ever journalism school in the country. His efforts at Washington College, author Charles Bracelen Flood asserts, entitle Lee “to a position in the first rank of American educators.”

This essay was originally published at The Imaginative Conservative.