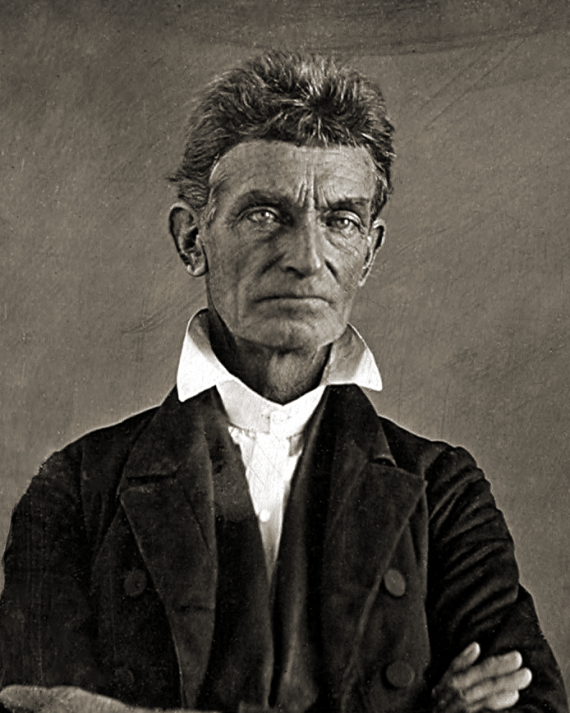

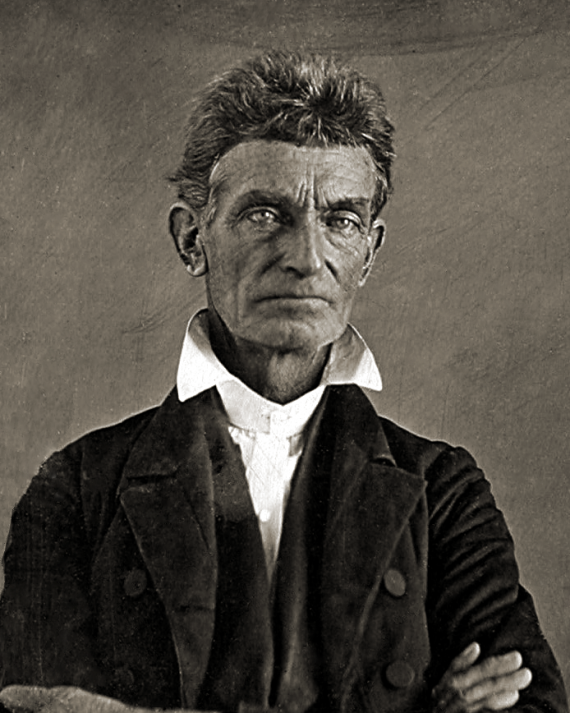

It is unsurprising that one of the antifa groups that have been making the news lately identifies itself with John Brown, the revolutionary abolitionist who was hanged shortly after leading an attack upon Harper’s Ferry in 1859. Brown’s career embodies the progressive fixation with being on the ostensibly “right” side of history, and as the attempted massacre of Republican senators by an unhinged Bernie Sanders activist suggests, Brown’s spirit is alive and well in 2017 America. Antifas and James Hodgkinson’s failed rampage are not the only signs of said spirit’s continuing presence, however. The ongoing purge from the South of Confederate symbols also reflects the triumph of Brown’s totalitarian utopianism over novelist-historian Shelby Foote’s “Great Compromise.”

For those unfamiliar with Foote’s expression, the term Great Compromise here refers to an unspoken understanding which supplemented the formal peace treaty signed by the opposing generals at Appomattox. The idea was that Southerners would accept the reality of their defeat and render dutiful service to the Union, especially in the military, even as Northerners agreed to honor Southern heroes and admitted that Southern culture and principles had made valuable contributions to America’s development. As a result, former Confederate general Joseph Wheeler served in the United States Army during the Spanish-American War, while the Kansas-born President Eisenhower generously praised Robert E. Lee as a man “selfless almost to a fault and unfailing in his faith in God.”

It is an understatement to say that the Great Compromise no longer holds. Thanks to Allan Bloom and neoconservatives hostile to the South, the consensus is now that the War Between the States was indeed a simple contest of Good Guys in blue versus Bad Guys in grey, and anyone who rejects such comic-book interpretations of history must be a relativist. Yet Northerners of goodwill might well ask themselves whether the wholesale repudiation of the South by American elites has not wrought considerable damage upon America as a whole. A case can be made that American society is becoming increasingly coarse, sordid, and perverse precisely because America’s leaders have in recent years decided to define the South as “the Other.” The result of defining America in opposition to the South has been the rejection of Southern values like honor, Biblical tradition, forms and courtesy, and deference toward the female sex and its unique role in sustaining civilization. Likewise, the large-scale rejection of Southern political ideals – states’ rights and decentralization, rurally-rooted republicanism, modest and constitutionally-restrained government – has played no small part in transforming American politics into what could be best described as a cold civil war.

In addition to being one of the last exemplars of the Great Compromise, Eugene Genovese of Brooklyn was also one of the most colorful intellectuals of our times. Though a Marxist for much of his career, Genovese seems to have been an unusually independent-minded one, for even in his Das Kapital phase he found himself defending against the attacks of liberation theology activists what seemed to him sensible and humane Catholic teachings. Over the years he grew more and more alienated from international socialism, until at last he left the Communist fold and came into the Church.

In The Southern Tradition Genovese evaluated Southern conservative thought from the perspective of an outsider. Among other things, he noted his leftist former colleagues’ tendency to self-righteously vilify and caricature the long-defeated, long-dead plantation owner. This inclination struck him as strange indeed, given that leftists themselves had promoted “a political movement that piled up tens of millions of corpses to sustain a futile cause and hideous political regimes.” Although he could still identify with many leftist ideals, he also believed that “the Left would have to learn some hard lessons from southern conservatives if it were ever to rescue itself from the overt totalitarianism of Stalinism and the disguised totalitarian tendencies that infect left-liberalism and social democracy.”

In contrast to most works by mainstream conservatives Genovese’s takes quite seriously the anxieties of Flyover Country, especially that portion of it found below the Mason-Dixon line. Indeed, were populist conservatism to turn truly ugly, America’s leading journalists, professors, and political operators would have only themselves to blame for having ignored Genovese’s analysis:

We are witnessing a cultural and political atrocity – an increasingly successful campaign by the media and an academic elite to strip young white southerners, and arguably black southerners as well, of their heritage and, therefore, their identity. They are being taught to forget their forebears or to remember them with shame […] It is one thing to silence people, another to convince them. And to silence them on matters central to their self-respect and dignity is to play a dangerous game – to build up in them harsh resentments that, sooner or later, are likely to explode and bring out their worst.

Genovese’s complex essay “The Chivalric Tradition In the Old South” does not ignore the worst of the South, but nonetheless focuses upon its best – namely, its aspiration toward nobility. This aspiration explains why so many antebellum Southerners made a point of employing anachronistic language, as when they would label a man knightly to signify approval of his conduct:

Exuberant southerners meant to draw attention to such presumed aristocratic virtues as gallantry, classical education, polished manners, a high sense of personal and family honor, and contempt for money-grubbing. These themes appeared frequently in publications and orations, most notably in college commencement addresses, for which the Middle Ages provided an especially favorite topic […] they cherished the courtly virtues as products of the Middle Ages and, specifically, of feudal and manorial life.

As a man of the left, Genovese had never held simpleminded, romantic illusions about medieval serfdom, much less life on the old plantation. At the same time he was also too common-sensical to mistake for an argument Mark Twain’s personal prejudice against Sir Walter Scott, the Southerner’s favored novelist. Men without chests might sneer at high-minded traditions like chivalry (particularly Southern chivalry) all they liked, yet the fact that a people did not always live up to its own principles “hardly rendered unworthy the ideal of the chivalric gentleman as a standard.” Even after allowing for much idyllic self-delusion on the part of the planter who styled himself a beneficent paterfamilias, any scholar studying the South is “still left with masters who knew what God and their consciences expected of them and what they assumed their neighbors expected or should have expected.” Genovese would not claim that the South is or ever has been a perfect society, nor would he claim that only Southerners have a sense of honor, nor would he deny the worth of characteristically Yankee traits like industriousness and a spirit of innovation. What he does insist upon is that America will never recover its collective sanity unless its leaders once again admit that, flaws or no, Dixie is a network of real, distinctive human cultures worth cherishing and fostering.

As for John Brown, no sharper contrast to the chivalric ideal could be found than the puritanical terrorist with whom Henry David Thoreau openly sympathized. Nor could a more chilling and ironic omen be found than the oft-neglected fact that Heyward Shepherd was the first civilian killed by Brown’s raiders. If we are at all prone to seeing symbols in history, reflecting upon this initial casualty of the irrepressible conflict must surely make us think twice about the ultimate effect of progressive zealotry upon actual, flesh-and-blood African-American communities. Shepherd was not only a baggage handler employed at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, but a free black man with a wife and children.