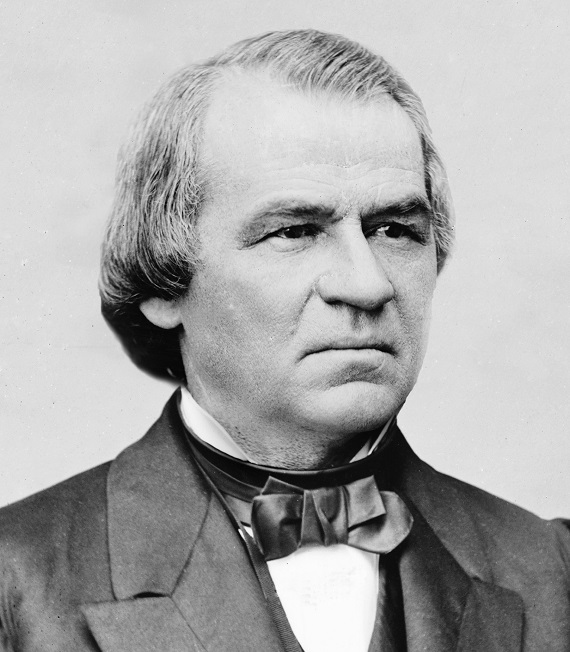

If one bothered to turn back the pages of history it should become quite evident that the 1868 impeachment of President Andrew Johnson bears a most eerie resemblance to the current two-count indictment that has been drawn up against President Trump by the Judiciary Committee of the present House of Representatives. A century and a half ago it was the Radical Republicans led by Congressmen Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and Charles Sumner of Massachusetts who controlled the House with an over eighty-six per cent majority, while today the House is in the hands of radical Democrats who hold a more than fifty-four per cent majority. Even though the agendas and targets of the Republicans of 1868 and those of the Democrats of today may differ, each of the parties were and are more than willing to trample on not only the Constitution, but also the accepted rule of law and even the basic canons of ethics, justice and morality. Officially, the lower legislative body has the power to act in such a partisan and unfair manner, as Article One of the Constitution gives the “sole power of impeachment” to the House of Representatives, with only a simple majority needed there to carry out the indictment, no matter how fallacious their case might be. However, Article Two of the Constitution which outlines the basis for the impeachment of any officer of the United States government, including the president, is a bit more ambiguous. While the Article clearly states that the specific crimes of treason and bribery are to be considered as definite causes for impeachment, the Constitution also added the indefinite phrase “or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors” and it this highly elastic latter phrasing upon which all the Articles of Impeachment have been prepared in the cases brought against both Presidents Johnson and Trump.

At the end of the War Between the States in 1865 and the assassination of President Lincoln the same year, the radicals who controlled the ruling Republican Party sought to wreak their vengeance against all those who had dared to exercise their Constitutional right of secession by basically denying them their legal status as American citizens, as well as imposing a draconian system of martial law on the eleven States of the defeated and prostrate Confederacy. It is certainly a moot question as to whether or not Lincoln, had he lived, would have put into practice the line from his Second Inaugural Address “with malice toward none and charity for all” and had either the desire or the power to restrain the radical elements that controlled his party. Clearly Lincoln’s successor, Vice-President Johnson, a Southern Democrat, had such a desire and proposed a more even-handed policy of Reconstruction for the defeated South, one which called for amnesty for former Confederates, the rapid restoration of the eleven seceded States back into the Union and allowing new local governments to be quickly created. The Republican Congress, however, ignored the new president’s wishes and not only passed their own far more harsh Radical Reconstruction program, but were able to override all the presidential vetoes of such legislation.

As a means of blocking the removal of any official charged with carrying out the Radical Republican mandates, Congress enacted the “Tenure in Office Act” in 1867 that effectively barred the president from taking such legitimate action and thus deprived him of his presidential right to remove any political appointee who served at what was rightly termed the “pleasure of the president,” even members of his own Cabinet. The Act was actually designed to protect one such individual, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, the Lincoln appointee who was a key figure in the vindictive and ruinous Reconstruction of the South and whom Johnson wanted to replace with the far more suitable and less radical General U. S. Grant. The president had vetoed the new Act on Constitutional grounds, but his veto was easily overridden by the radical majority in Congress and thus became law. Using Johnson’s violation of the Act in dismissing Stanton as its basic charge, the House drew up eleven Articles of Impeachment the following February, nine of which were based solely on the Act. A tenth Article spuriously charged Johnson with opposing the Army Appropriations Act of 1867 which, as commander-in-chief of the Army, he had every right to do. The final and most blatantly partisan Article charged that in some of the speeches made by President Johnson, he had heaped what was termed “disgrace, ridicule, hatred, contempt and reproach” on Congress. Even though Article Eleven amounted to little more than a charge of libel and/or slander, it was the initial Article to be sent to the Senate the next month for a vote.

The Radical Republicans thought it would be a foregone conclusion that when this single charge was presented to the Senate, their party’s forty-two to twelve majority in that house, as well as having one of their radical cohorts presiding over the trial, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Salmon Chase, Lincoln’s former secretary of the Treasury, would insure the needed two-thirds vote to gain a conviction. That was not to be the case though and after three months of heated testimony, the polling of the fifty-four voting senators produced only thirty-five votes for conviction . . . one vote less than the needed two-thirds. What tipped the balance in Johnson’s favor was the fact that seven of the more moderate Republican senators, including Senator Edmund Ross of Kansas who cast the final vote and on whom the Radicals had counted to vote guilty, had rejected the House’s machinations and joined the twelve Democrats in voting Johnson not guilty. Unwilling to accept the verdict, the Radicals called for a ten-day adjournment and on May 26th a second vote was called for on two of the remaining Articles which produced the exact same thirty-five to nineteen vote that finally gained Johnson’s acquittal. Shortly after the trial, the “Tenure in Office Act” was severely amended and finally repealed entirely in 1887. In the 1920s, an attempt was made to enact a similar type of legislation, but this time it was taken before the Supreme Court in the case of Myers v United States. In 1926, by a six to three decision, the high court ruled that the president, without the approval of Congress, has the sole power to remove any executive branch appointee, including Cabinet members. This ruling finally vindicated Johnson’s veto of the 1867 Act, as well as proving that his impeachment was nothing more than a political sham.

Just as in Johnson’s case, where the primary charges against him were based on a tenuous and extremely partisan law that was later judged to be unconstitutional, the current abuse of power and obstruction of Congress charges in the current two Articles of Impeachment against President Trump run a close parallel to the eleven against President Johnson in that they are also based on equally tenuous and partisan charges. In Trump’s case, the primary charge revolves around the majority party’s interpretation of a private telephone conversation between two heads of state. There is, however, an added element in both of the current Articles of Impeachment that goes even further and is even more devious than in those brought against President Johnson . . . one which also dates back to the 1860s that involves disqualification for any future Federal office . . . and one, so to speak, that could give President Trump a life sentence without a chance of parole.

This matter concerns the disqualification phase as set forth in Article One, Section Three, Clause Seven of the Constitution which states that a judgement in a case of impeachment can also consider the “disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States.” The problem is, however, that the Constitution provides no specific guidelines as to how such punishment should be administered, such as whether the removal and disqualification should be considered as separate matters and if so, should they be voted on separately. The first time this clause was ever used in an impeachment case was in the 1862 trial of West Humphreys, a Federal judge from Tennessee. The judge had supported Tennessee’s secession in 1861 and was appointed the district judge for the State of Tennessee by the Confederate government. For this “high crime,” Humphreys was not only impeached in absentia by the Republican House of Representative the following year and then convicted by the Republican Senate by a more than two-thirds vote, but also barred from ever holding any office in the United States by a simple majority vote in the Senate . . . thus setting a precedent for such actions in the future. For some reason, however, the disqualification clause was not considered in President Johnson’s impeachment trial six years later. The clause did not appear again until 1913 when Robert Archibald, an associate judge of the U. S. Commerce Court, was also impeached, convicted and barred from ever holding any federal office. Like Judge Humphreys, the second judge’s additional punishment was decided by a majority vote, with the 1862 case against Humphrys being cited as the precedent. The third and last time the disqualification clause was ever injected into a Federal impeachment trial was in 1936 during the case against Federal District Judge Halsted Ritter of Florida. After the Democratic-controlled Congress impeached and removed Ritter from office, the constitutionality of the vote on Ritter’s disqualification was debated and the simple majority-vote precedent was once again invoked.

Moving the calendar ahead eighty-three years, we come to the present case against President Trump in which the two Articles of Impeachment include the wording that Trump should not only be impeached, tried and removed from office, but that he also warrants “disqualification to hold and enjoy any office of honor, trust, or profit under the United States.” As the precedent set in the three previous trials of Federal judges has never been reversed by the Senate or adjudicated in any Federal court, the disqualification of President Trump would probably be decided by a separate majority vote, rather than the two-thirds vote on the two Articles of Impeachment. Therefore, even though there is little doubt that a two-thirds vote for conviction and removal from office could not be obtained in the Republican-controlled Senate, if disqualification is brought to a separate majority vote the picture would be far less clear in a Senate where the GOP has only a fifty-three to forty-seven vote majority and just four Republican defections could tip the scales of justice against the president. In the case of a tie vote, unlike a regular Senate session or trial, a presidential impeachment trial is presided over by Chief Justice Roberts of the Supreme Court and he would cast the tie-breaking vote rather than the vice-president.

Rebecca Ballhouse, the White House reporter for the Wall Street Journal, has pointed out the anomaly that had the disqualification clause not been included, even if the president were to be convicted and removed from office, he could still run for reelection next year. A second possible and more nefarious scenario, however, would be the case of President Trump being acquitted on the Articles themselves by a two-thirds vote, and then by a simple majority vote, being disqualified from taking office even if he is reelected. The Senate as a Court of Impeachment will be sailing in highly unchartered waters, as the clause citing disqualification has never been used in a presidential impeachment trial and the compass for the Senate guidelines as to the procedures to be followed for such a vote seem to point in two different directions. While the Senate rules state in one section that if, after a vote on the Articles, the respondent is found not guilty on all charges, the Court of Impeachment would then adjourn. The following section, however, says that adjournment would take place after a verdict of guilty or not guilty has been rendered “and the disposition of the disqualification, if presented” has taken place. Since the procedure for the taking of such votes is not clearly delineated, new guidelines may have to be established for a trial that could result in a truly catch 22 situation.

As in 1868, the overriding desire to rid the country of what is somehow considered to be an illegitimate presidency has led to a hastily devised impeachment based on extremely questionable evidence. In the case of Andrew Johnson, when Lincoln ran for reelection in 1864 against General George McClellan, he feared that it would be a close contest. In seeking to balance the ticket for a stronger showing at the polls, Lincoln cast aside Vice-President Hannibal Hamlin of Maine and selected Johnson as his new running mate, an experienced Democratic politician from Tennessee who had remained a strong Unionist and an outspoken critic of secession. Johnson was not, however, looked upon with any degree of favor by the ruling Radical Republican and when he attempted to moderate their efforts in punishing the South, the radicals sought to remove him from office and since there was no vice-president, replace him with one of the leading Radical Republicans, Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio, the president pro temporare of the Senate. Today, many Democrats, as well as some Republicans, likewise cannot accept a Trump presidency even though it was gained in a legitimate election, and have been attempting for almost three years to find some means to impeach and remove him from office, first with an investigation of the mythical Russian collusion which was ultimately blown out of the water, and then with the equally unfounded Ukrainian “quid pro quo” charge. While the House Democrats realize that any impeachment would certainly fail to win a conviction in the Republican-controlled Senate, even if a handful of anti-Trump Republicans should jump ship, they had hoped that the black mark of impeachment alone, no matter how much of it was constructed on a foundation of political mud, might be just enough to seriously damage Trump’s reelection bid next November. Now, however, an additional joker has been slipped into the already stacked impeachment deck, namely the remote possibility of not allowing Trump to take office even if he is reelected next year. It is indeed a partisan maneuver to which the Radical Republicans of 1868 would heartily give their vote of approval, as well as one that would cause the Founding Fathers to spin in their graves.