The present feverish campaign to remove Confederate monuments and other symbols which offend certain loud groups in our society began in earnest back in 2015, after the murder of several black parishioners in a church in Charleston, South Carolina. But that movement dates back much longer. Its real origins go back to the 1960s and early 1970s, and the triumph of a form of what has been called “cultural Marxism” in our universities and colleges, and a resultant and progressive transformation of views of American history in our popular culture.

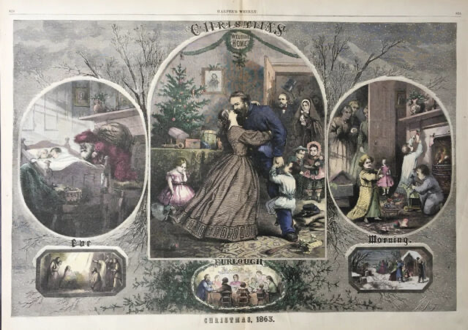

Recall that even into the late 1950s and certainly up until the “Civil War Centennial” (1960-1965) not only in our popular culture, but in most of the history taught in our schools and colleges, the South, and in particular, the Confederacy, were viewed with some respect, if not sympathy. If slavery was condemned—and not just in the Northern states, but also by the South—still, in particular, the veterans of the tragic Confederate military odyssey, were portrayed by Hollywood in such films as “The Raid” (Van Heflin), “Rocky Mountain” (Errol Flynn) or “Jesse James” (Henry Fonda, Randolph Scott), as noble and heroic figures doing their duty. And who can forget such popular television programs as “The Rebel” (1959-1961, with Nick Adams) or “The Gray Ghost (1957-1958, with Tod Andrews) with their romantic portrayals of those soldiers fighting for the “lost cause”?

And Southern culture and society, itself, was seen with considerably more nuance and appreciation than today’s rigid and universal damnation. Again, Hollywood produced such superb cinematic visions as John Ford’s “The Sun Shines Bright” and Disney’s “Song of the South,” and countless others.

In the academy, classic histories by Avery Craven, William Dunning, Charles W. Ramsdell, Charles Sydnor, Francis Butler Simkins, and others were prominently used and taught in colleges. And the monumental ten-volume, “A History of the South” (published by the LSU Press) seemed to offer the final word on discussions of the Southern past. Yet, by the mid-1960s newer historians—Kenneth Stampp, Stanley Elkins, and others, influenced by a more Leftist ideology and more concentrated on the role of race—soon dominated the writing of Southern and American history. It was their students and succeeding generations of historians who made no excuse for their blatant Marxism, and whose views eventually permeated not only the academia, but also our popular and political culture.

The dominant narrative for these ideological academics was that “race” and “racism” had been and continued to be the central issues that affected, influenced, and determined the rest of American history. And, thus, the logic went, since the Old South, most prominently the Confederacy, defended slavery and was then, by definition, “racist,” the symbols and monuments that memorialized it in any positive way represented that “racism” and a “racist” past that needed not only to be re-interpreted, but “cleansed.”

But the assault on the Confederate past and on its visible artifacts and reminders, its flags, its monuments, it symbols, is, as we clearly now see, only the tip of the iceberg. For those who wish to remove our monuments honoring General Lee or Jefferson Davis, have made it manifest that Lee, Jackson, and Beauregard are only the first step in a much larger and all-consuming campaign to thoroughly “purify” and radically transform American society.

A few weeks ago one small frenzied group in Durham, North Carolina, the Workers’ World Party, organized a violent demonstration and the destruction of the Confederate veterans’ monument in that university city. Like other such groups—the “antifa” organizations, Black Lives Matter, and similar organizations—Workers’ World supporters call for: the abolition of capitalism, disarming of the police and ICE agents, the fight for Marxist revolution, and the defense of “Black Lives Matter.” All symbols and reminders of “white supremacy” and of “racism” must be eradicated and destroyed. And those symbols are not limited to the Southern Confederacy, but encompass nearly all of this country’s Founders, most of its 19th century presidents and political leaders, its earliest discoverers and colonizers, and, in fact, its basic historic culture.

What is remarkable is the extent to which such avowedly extremist and Communist organizations now seem to dictate and shape the larger discussion and debate over monuments and symbols. It is as if the Democratic Party, the near entirety of the media, and vast swathes of the GOP frantically accept the narrative of “racism” as the central and dominant issue in American history, from which all else, all events, all history, flow. And, as such, this domination represents the general triumph of cultural Marxism in establishing both the standard terms of acceptable debate and the required outlook, against which no dissent is permitted.

Given this situation, it is extremely difficult for me to have any sympathy whatsoever for WRAL-TV’s main newscaster, David Crabtree, in Raleigh, North Carolina, who continues ad nauseum to blubber about the “hurt” and the “hatred” that monuments to Lee or to the “Women of the Confederacy” (on the North Carolina State Capitol grounds) inflict on poor black youth living in the Tar Heel State’s capital city in 2017. Like other “religiously-oriented” personages who have accepted the cultural Marxist narrative, Crabtree clothes his views in a language of supposed Christian love and charity, and a desire for “social justice.” But in fact, he has swallowed whole hog the Marxist vision of society and de facto turned his back on historic, traditional Christian belief and on our historical and cultural legacy. He has become, perhaps unwittingly, one of those “public dogs” wagged by the revolutionary Marxist “tail,” who uses his public persona and widely-heard voice to advance its longer range program of destruction, deformation, and complete transformation of what is left of the American nation.

Such pawns of the Revolution are useful idiots, but useful only to a certain point, after which they are usually discarded as having fulfilled their purposes, but not permitted to “cross over Jordan into the Promised Land.” Like the Mensheviks and Social Democrats in Russia in 1918, they will be eliminated or liquidated after the Revolution moves on to it next stage.

Crabtree and others like him may fret about the “pain” that a statue to Lee may give, but his logic leads ineluctably to much more than just the purging of Confederate images: it leads to the denuding of American history and the end of anything resembling the America created 241 years ago—it leads to the fearsome silencing of those who oppose that transformation—and it may well lead to the scaffold, as all such fanatical revolutions usually end in pools of blood.

Frankly, those facilitators of revolution always seem to get finally what they deserve—a bullet to the back of the head, as they wonder, simple-mindedly and incredulously, why their “social justice” concerns weren’t implemented by their one-time allies amongst the hard core extremists.

For the rest of us it is to do our best to defend our patrimony, to demonstrate—like the articles of the Nicene Creed where denying one precept undermines and implicitly denies the others—that to destroy Confederate symbols opens the door wide to the destruction of all our symbols and the radical Marxist redefinition of the American nation, itself.

It appears an almost insuperable task, but it is our duty before the shadow of our ancestors and before the verdict of history.