What does the South have to offer that is valuable to humanity, to civilization?

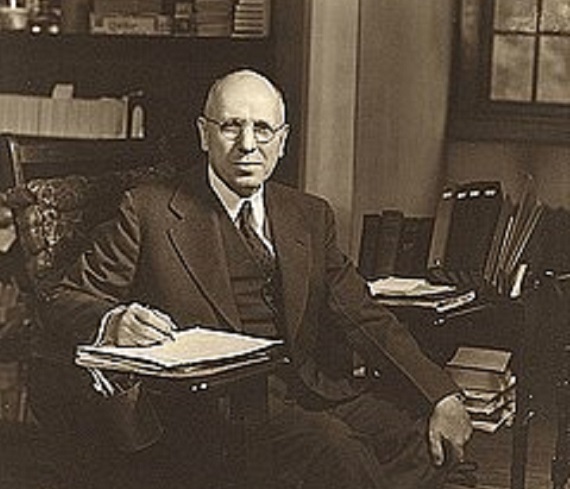

In 1939, the Pulitzer prize-winning historian Douglas Southall Freeman proposed an answer to this question in his book The South to Posterity. He subtitled it An Introduction to the Writing of Confederate History, but it was something more than that. In presenting the works of Confederate literature that had the most sincerity, human appeal, and enduring interest, Freeman was also making “a petition to the court of time.”

He maintained that these works of historical literature would always stand as solid evidence that the South had “fought its fight gallantly, and, so far as war ever permits, with fairness and decency; that it endured its hardships with fortitude; that it wrought its hard recovery through uncomplaining toil, and that it gave to the nation the inspiration of personalities, humble and exalted, who met a supreme test and did not falter.”

Freeman made his case for the South to the “final tribunal” of history and proclaimed that these words should be written across its record: “Character is Confirmed.”

Earlier in the 1930s, the celebrated English writer and critic G. K. Chesterton gave his thoughts on what the “Old South” had to offer the world in his essay “On America,” in which he asserted that, although the twentieth century was the “Age of America,” there was “a virtue lacking in the age, for want of which it will certainly suffer and possibly fail.”

That missing virtue, according to Chesterton, was honor.

“America,” he wrote, “is crying out for the spirit of the Old South … And we need the Southern gentleman more than the English or French or Spanish gentleman. For the aristocrat of Old Dixie, with all his faults and inconsistencies, did understand what the gentle man of Old Europe generally did not. He did understand the Republican ideal, the notion of the Citizen as it was understood among the noblest of the pagans. That combination of ideal democracy with real chivalry was a particular blend for which the world was immeasurably better; and for the loss of which it is immeasurably the worse.”

More recently, in his book Why America Failed (2012), cultural historian Morris Berman expressed similar sentiments, characterizing the antebellum South as a culture focused on “honor and community,” and further stating, “In its flawed and tragic way, the Old South stood for values that we finally cannot live without if we are to remain human.”

In The South to Posterity, one man whose story Douglas Southall Freeman offered as testimony to the “court of time” was a young Confederate cavalry officer from South Carolina, Alexander Cheves Haskell. Freeman had recently read a biography of Haskell which drew heavily on his memoir and correspondence, and he singled out a letter Haskell penned in 1863 as among the finest examples of “the war-time correspondence of high souls” and “one of the most beautiful born of war.” Freeman included only a portion of this letter in his book, but all of Haskell’s wartime letters have finally been collected and published as part of his family’s correspondence in my new book An Everlasting Circle: Letters of the Haskell Family of Abbeville, South Carolina, 1861-1865.

An Everlasting Circle includes many outstanding letters written by a remarkable and prominent family that sent seven sons to war. Dr. James E. Kibler has contributed an excellent afterword to the book that comments on the literary value of the letters and the kind of civilization that could produce a family like the Haskells. It was a civilization shaped by classical learning and orthodox Christianity.

The classical education of the Haskells, Kibler wrote, was “not window dressing, but instead allowed comprehension of the Western world’s definition of the civilized man. Southerners of their class understood that they were the upholders of that tradition, so that a Southern Agrarian writer like Allen Tate could declare of Southern traditionalists, ‘We must be the last Europeans—there being no Europeans in Europe at present.’ The Haskells lived their own particular version of the agrarian ideal with the historical and religious scheme of Europe as their example, source, and prototype. Their letters provide a valuable window into that world … [and] make it possible to put a face on these abstractions. They display chivalry in action to the extent that the term may be defined thereby. Honour and chivalry are brought down to the personal level. Here the concepts entail far more than duty and a sense of obligation understood in the gentlemanly code as noblesse oblige.”

At the time The South to Posterity was published, recent popular books such as Gone with the Wind had sparked a strong public interest in reading more about the Confederate era, and Freeman’s book was written partly in response to that interest. In 1939, while America was still enduring the Great Depression, and the world was about to be plunged into another great war, Freeman speculated that the reading public’s interest might be explained by the terrible troubles that many people were facing at that time in the twentieth century.

In his introduction he mused, “Do the woes of the individual in this time of economic revolution and spiritual doubt seem less in the overwhelming calamity of the South? It may be so. To spirits perplexed or in panic there may be offered, in the story of the Confederacy, the strange companionship of misery.”

More importantly, Freeman hoped that his book would provide readers inspiration, and even courage, through the stories of “men and women unafraid.”

Alexander C. Haskell saw the war as a great tragedy, and because of it, like most Southerners, the Haskells suffered many severe losses and tribulations. Yet, as James E. Kibler observed, their letters also offer an inspiring story of “devotion to home, family solidarity, faith, virtue, fidelity, sacrifice, bravery, and a strength of character that makes it possible to survive terrible loss and trauma.”

The wartime story of the Haskells is one marked by its share of ruin and tragedy, but it is also a chronicle of honor and faith—some of the South’s priceless gifts to posterity.