It is generally thought that when the earliest Homo sapiens arrived on the scene in Africa and Asia less than a hundred-thousand years ago, all of North and South America was devoid of human habitation. Most in the scientific community also contend that it was no more than twenty to thirty-thousand years ago, as the glaciers from the last Ice Age slowly retreated from most of North America, that the Americas began to be populated by the initial travelers from Asia who made the long trek across the land mass called Beringia that is today the Bering Sea which stretches between Siberia and Alaska. This eastward Asian migration lasted for some two thousand years prior to the occurrence of one of the early periods of natural global warming that finally submerged the land route. However, more recent findings by Dr. Albert Gooding, an archaeologist at the University of South Carolina, might seem to indicate that at least some type of humanoids may have lived along the Savannah River about fifty-thousand years ago. Regardless of this later evidence, there is little doubt that the main body of the South’s initial settlers, those who are now termed Native-Americans, was a branch of those ancient migrants from East Asia.

During the many centuries following their initial crossing into North America, those East Asians began their southward movement along both sides of the Continental Divide. When the main body finally reached the base of the vast Wisconsin Glacier near present-day Colorado, various branches turned east, west and south . . . with many along each path ending their journey to form the numerous tribes that would ultimately inhabit all of North and South America. While those who headed toward the southeast would create more than sixty different tribes throughout the South, the five that made up the so-called “Civilized Tribes,” Cherokee, Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw and Seminole, figure most prominently in Southern history . . . with the Cherokee, who arrived in the South about ten-thousand years ago, being the most notable. Until the latter part of the Eighteenth Century, the Cherokee Nation represented an area of approximately 140,000 square miles that took in large sections of Alabama, Georgia, North and South Carolina, Kentucky and Tennessee.

After the arrival of the European settlers, however, conflicts between the new and older American immigrants arose, and a series of agreements, such as the 1819 Treaty of Washington negotiated by Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, saw a rapid ceding of tribal land to the United States government. It all came to a climax in 1830 during the administration of Andrew Jackson with the passage of the Indian Removal Act which culminated in the infamous 1838-1839 “Trail of Tears.” This tragic event saw most of the remaining 15,000 Cherokee, as well as the members of the other four “Civilized Tribes” in the Southeast, being forcibly removed to the Indian Territory that is now the state of Oklahoma. A small group of Cherokee, however, were granted citizenship by North Carolina and have remained in the western part of that state to this day . . . the only Native-American tribe in North Carolina to be recognized by the federal government.

The Cherokee had a highly advanced culture which, unlike other Native-American tribes, included a written, syllabic language that had been created in the early Nineteenth Century by Sequoyah, a native Cherokee teacher and silversmith from Tennessee. Due to his unique method of writing, which was widely used throughout the Cherokee Nation, the degree of literacy among the Cherokee was higher than that of many European settlers in the area. While a number of Cherokee had become Christians, as well as adopting some European modes of dress and living, they remained a warlike people who sought to retain their independence in the South. However, even though the Cherokee had bitterly fought the English settlers who were attempting to encroach upon their lands, they still sided with the British in their colonial conflicts with the Spanish and the French. This was also true during America’s Revolutionary War where the Cherokee, like their cousins to the north, the Iroquois, allied themselves with England.

After their relocation to the Oklahoman Indian Territory, many Cherokee adopted an even more pronounced European-American life style . . . living and dressing as any other Southerner, with many becoming plantation owners and slaveholders. In most respects, their culture became a mirror-image of that which still existed in the Southern states they had left behind. To a lesser degree, this was also true with members of the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole tribes with whom the Cherokee shared the Indian Territory. This affinity with the South became far stronger during the mid-Nineteenth Century due to the many broken promises being made to the tribes by the federal government, particularly that the territory would be completely free of white settlers. For that reason, while some of the Native-Americans remained loyal to the Union during the War Between the States, almost all the Chickasaw and Choctaw, as well as a majority of the Cherokee, Creek and Seminole sided with the South, and the Indian Territory virtually became the twelfth Confederate state. Furthermore, two Cherokee chiefs, one a true Native-American and the other a European-American who had been adopted by a Cherokee leader, became central figures in both the War Between the States and the Cherokee struggle for independence.

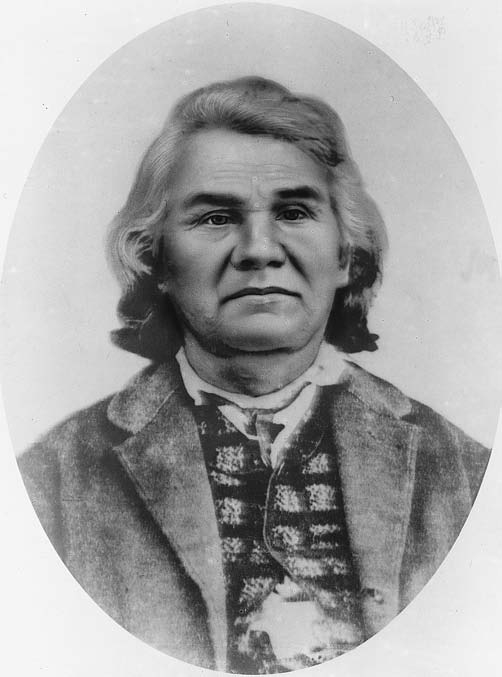

The first, Stand Watie, was born a Christian in what is now Calhoun, Georgia, in 1806, the son a full-blooded Cherokee father and a half-Cherokee mother. By the time he was twenty, his father had already become a wealthy plantation owner and slaveholder in the Oothcaloga region of the Cherokee Nation. Stand Watie and his brother Elias also published the first Native-American newspaper, the “Cherokee Phoenix,” which took a strong editorial stance against repressive federal anti-Indian laws, as well as the encroachment into Cherokee land by white settlers, particularly after gold was discovered in northern Georgia. After passage of the federal Indian Removal Act in 1830, Georgia rushed to confiscate most of the remaining Cherokee land, including the Watie plantation, as well as sending in the state militia to destroy the “Cherokee Phoenix.” Watie openly opposed the order to move to the Indian Territory, but finally became one of the leaders who negotiated the Treaty of New Echota with the federal government in 1835 which ceded the remaining Cherokee Nation to the United States in return for the granting of certain rights in the Indian Territory.

After the treaty, the Watie family and their slaves followed the others westward along the “Trail of Tears” but because the giving up of tribal land was deemed a capital crime under Cherokee law, Watie and his relatives were put on trial and all except Stand were sentenced to death. Watie later became a major plantation owner in the Indian Territory, and from 1845 to 1861 was a member of the Cherokee Council. He served as speaker of the Council for two years and in 1862 became the main Cherokee chief. When the War Between the States began, and a majority in the Cherokee Nation voted to join the Confederate cause, Watie organized a local cavalry regiment, the 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles, and was commissioned a colonel in the Confederate Army. He was promoted to brigadier general in 1864, the only Native-American on either side to hold that rank, and put in command of the First Indian Brigade in General Kirby Smith’s Army of the Trans-Mississippi. After the War, Watie led a failed effort to renegotiate a favorable Cherokee peace treaty with Washington, was stripped of his tribal leadership by the Union government, and returned to the territory to rebuild his plantation.

The second prominent figure in Southern Cherokee history was William Holland Thomas, a distant cousin of Presidents James Madison, Zachary Taylor and Jefferson Davis, as well as Confederate Generals Robert E. Lee and Richard Taylor. Thomas was born in Haywood County, North Carolina, in 1805, the son of aristocratic Welsh and English parents. His father, who had died several months before William was born, served in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War and had been given a land grant in North Carolina after the War, while his mother was the grandniece of Lord Baltimore, the founder of the Maryland Colony. As a young man, Thomas worked at a Cherokee trading post where he learned the Cherokee language and was eventually adopted by the local Cherokee chief, Drowning Bear (Yonaguska). Thomas later became a leading businessman and self-taught lawyer, as well as serving in the North Carolina Senate from 1848 to 1861. After the death of Chief Yonaguska, Thomas was selected as the tribal leader of the Cherokee who had been allowed to remain in North Carolina, the only white person to ever become a Cherokee chief.

When North Carolina seceded from the Union in 1861 and joined the Confederacy, Thomas had opposed the state’s actions. However, once the die had been cast, he raised a personal fighting force of over a thousand local volunteers made up of two battalions, one Cherokee and the other white. By 1863, Colonel Thomas’ unit, known as Thomas’ Legion of Indians and Highlanders, would more than double in size with the addition of another Cherokee battalion, two companies of engineers, two infantry companies from the 16th North Carolina Regiment and an artillery battery. The Legion served under General Henry Heth in major defensive actions throughout western North Carolina and east Tennessee which successfully kept Union troops out of the area, as well as later fighting in Virginia as a unit in General Jubal Early’s Shenandoah Valley campaign of 1864. After his Legion, which had never lost an engagement against Union forces, fired the symbolic “last shot of the War” east of the Mississippi on May 6th, 1865, in Waynesville, North Carolina, Colonel Thomas surrendered the unit and returned home. While he had hoped to resume his business, political and tribal activities, Thomas’ mental health rapidly declined, perhaps due to the then unknown Alzheimer’s disease, and within two years he was declared insane and sent to a mental hospital in Raleigh. Thomas remained hospitalized until his death in 1893 at the State Mental Hospital in Morganton, North Carolina, but he remained sufficiently lucid a few years earlier to assist the noted ethnologist, James Mooney of the Smithsonian Institution, in Mooney’s major studies of the Cherokee and other Southeastern tribes.

Today, those ancient Asians who populated the South so many millennia ago are generally regarded as a lesser chapter in the pages of Southern history, with only a mere handful of their descendants still remaining in the area. In each of the Southern states but one, Native-Americans make up less than one per cent of the population . . . the one exception being North Carolina, where the small Cherokee community that was once headed by William Thomas still represents over one per cent of that state’s total population. However, the general acceptance of Native-Americans, as well as Hispanics and free-Blacks throughout the ante-bellum South, and the active participation of those minorities in daily Southern life, including their service in the War Between the States, certainly demonstrates a sort of homogeneity of variance that existed between white and non-white in that bygone era. There is also little doubt in the minds of many in the South today that had the Southern states been allowed to depart in peace in 1860, and the ravages of Union aggression and reconstruction had never taken place, the hated bird “Jim Crow” would never have found a place to roost in Dixie.