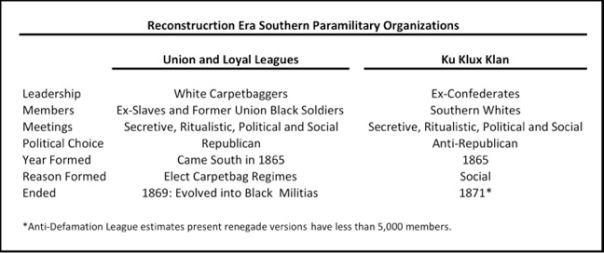

The Union League is one of the most cryptic of Civil War and Reconstruction era topics even though it was a wellspring of tyranny. Together with the Loyal League identical twin, Southern chapters prompted the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) to evolve from an obscure social club into a violent anti-Republican, and therefore anti-black, vigilante group.

The first Union Leagues lodges were formed in the North to support Republicans after Democratic gains in the 1862 wartime elections. According to historian Christopher Phillips the Leagues “demanded undiluted loyalty to the wartime polices of Abraham Lincoln.” They believed there was no such thing as a loyal opposition. Voters either supported Lincoln, or they were traitors. “Western Loyal Leaguers fought dissent with more than words. In central Illinois, one woman claimed that Republicans ‘were forming Vigilance committees to…[identify] every man and woman…not loyal to Lincoln.’” Even non-voters were not exempt from violence. In 1863 Leaguers tarred and feathered seven Ohio women, including one who was a widow of a recently deceased Union soldier.

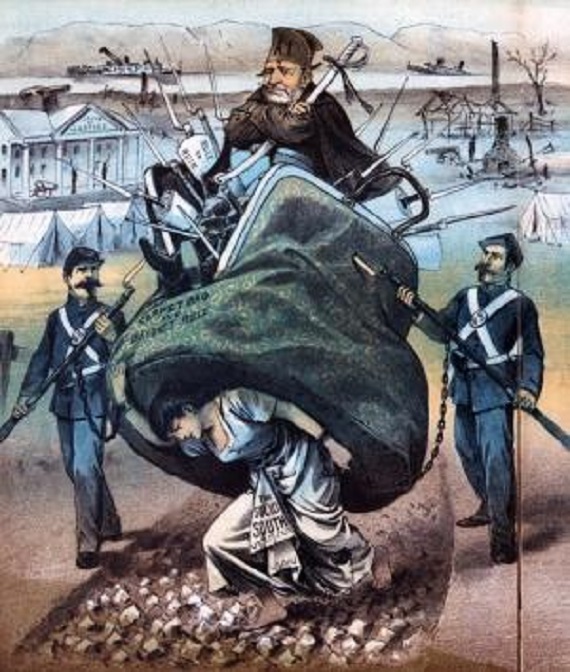

At the end of the war, League chapters opened in the South to serve as rallying points for whites that had opposed the Confederacy. After Southern blacks were permitted to vote for state constitutional conventions by the dubious authority of the 1867 Reconstruction Acts, most Southern whites dropped out as blacks flooded into the Leagues. The remaining whites became Scalawags and were soon joined by Northern Carpetbaggers.

The new goal for the Southern leagues, which was shared with the Freedmen’s Bureau, was to make sure that blacks registered to vote and voted Republican. By terms of the Fourteenth Amendment, blacks composed a majority of voters in five of the eight former Confederate states permitted to vote in the 1868 presidential election. They composed a sizeable minority in the other three.

The Union League recruited members with a cult of secrecy and exaggerated promises. Members were indoctrinated to believe that their interests were perpetually at war with Southern whites that were falsely accused of wanting to put blacks back into slavery. Ex-slaves were told their continued freedom depended upon the supremacy of the Republican Party. Accordingly, they voted Republican like “hordes of senseless cattle.”

One member explained that the Union League was the “place where we learn the law.” Another member said that he always voted Republican because “I can’t read and I can’t write…We go by instructions. We don’t know nothing much.” One North Carolina chapter was told that if Republican Ulysses Grant won the 1868 Presidential election, lodge members would be given public offices, farms, and mules. The state voted for Grant.

Black female supporters vowed that they would not consort with, or marry, men who were not League members. Ex-slaves who were reluctant to join because of friendship with their former masters were beaten and some were murdered. A number of lodges organized military units that trained regularly and inevitably clashed with armed whites.

Often lodge organizers were employees of the federally funded Freedmen’s Bureau, which held the loyalty of most Southern blacks by spring 1866. Consequently, the Bureau failed at what should have been its primary objective: to promote understanding and tolerance between Southern blacks and whites. Unfortunately, its political tactics and racial agitation redounded to the detriment of blacks as the KKK evolved into an even more violent and stronger counter-force, especially after Union Leaguers became the backbone of the Carpetbag state militias.

Two years after the end of the Civil War, the one million-man Union Army dwindled to about 50,000. Although 20,000 federal troops remained deployed in the South to enforce martial law and prevent a restart of the rebellion—a much feared in the North—Congress wanted an even stronger force in place after the region once again held elections. The parsimonious Republican-controlled Congress settled on a two-step approach.

First, in 1867 it effectively abolished the white militias of the unreconstructed Southern states. Second, after the 1868 elections put Carpetbag regimes in place a number of Southern states created new militias composed almost entirely of former black Union League members. As with all militias, they were funded by revenues from the respective states thereby obviating the need for a federal subsidy.

Author John Chodes writes, “[These] militia [were] to be used as the private armies of the carpetbag governors…In addition to insuring that voting by terror kept them in power, these militia forces defended against other ambitious carpetbaggers who attempted to usurp illegal power with illegal force.” Such Republican Party splits led to the demise Carpetbag governments in Arkansas, Tennessee, and Louisiana. Two opposing militia even fought one another during the Arkansas division, know as the Brooks-Baxter War.

The militias, however, may have done more to alienate Southern whites from the Carpetbag regimes than did the Union Leagues, per se. First, they had the authority of state government behind them, even when exercised in an irresponsible or racially discriminatory manner. Second, impoverished whites had to pay most of the taxes required to fund them.

Although less potent—and far less notorious—than the KKK, the Union Leagues and Carpetbag militias warrant more scrutiny by present-day historians. Always a good measure of political correctness, the Wikipedia article for example provides nothing about the Union League’s darker side

My Civil War Books

The Confederacy at Flood Tide

Lee’s Lost Dispatch and Other Civil War Controversies

Trading With the Enemy

Co. Aytch: Illustrated and Annotated

One Comment