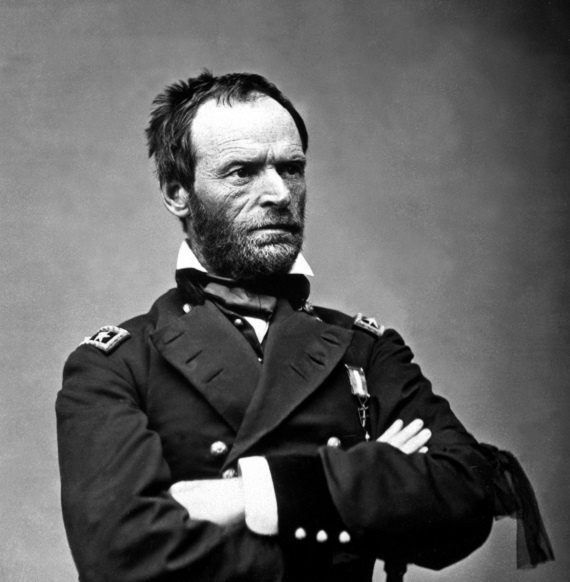

In 1864, General William T. Sherman wrote to a fellow Union officer that the “false political doctrine that any and every people have a right to self-government” was the cause of the war that had been raging in America since 1861. The general was forgetting, or ignoring, that this very “doctrine” had led the American colonists to declare their independence from Great Britain in the previous century. In the same letter, Sherman referred to state’s rights, freedom of conscience, and freedom of the press as “nonsense” and “trash.”

Devoted to the union and a powerful central government, he was willing to wage total war against fellow Americans who were fighting for independence and self-determination, and in the winter of 1865, many of the men who followed General Sherman cooperated with him in his intention to “smash South Carolina all to pieces” with malevolent glee. One South Carolina gentleman, a resident of Fairfield District, when asked if he had been visited by “rough men” (meaning Sherman’s soldiers), answered that he had been visited by “a legion of devils, not by men.”

After the city of Columbia, South Carolina, was sacked and burned by Sherman’s troops on February 17, 1865, one of its citizens, J. J. McCarter, recorded the following observation in his journal:

Both officers and men seem to vie with each other in punishing this town for the prominent part she bore in the rebellion (revolution). They were all deeply imbued with the sentiment of “Union.” “This glorious Union” was constantly on their lips, like the crusaders under Peter the Hermit they wanted to reestablish the Union even if by doing so they annihilated the present population … This strange fanaticism pervaded the whole army from Sherman down to the meanest private in the ranks …

“The Union must & shall be preserved” says the robber who presents his carbine at your head & demands your watch, fine jewelry. “This Union shall be preserved” says the ruffian who breaks your furniture, rips open your bedding, & then fires your house. The widespread desolation which Sherman caused in his march from Atlanta to Savannah & from thence to Columbia, was all done to preserve the Union—this glorious Union. The people who inhabited the desolate region were no more considered than the chaff before the whirlwind. ‘The life of the nation must be preserved’ says Seward no matter at what cost—even of the lives of this whole generation. To one who looks upon government as a means of ensuring life & property such language sounds like the ravings of insanity. But this insanity had evidently taken possession of the Northern & Western mind, as was fearfully developed in the campaign of Sherman.

The unpublished journal of James Jefferson McCarter (1800-1872) is one of the eyewitness accounts now available in a new book from Shotwell Publishing, A Legion of Devils: Sherman in South Carolina. A partner in the business of Bryan & McCarter, booksellers, Mr. McCarter recorded many horrific details about the night of the city’s destruction and its aftermath, noting for instance, that “The bodies of several females were found in the morning of Saturday stripped naked & with only such marks of violence upon them as would indicate the most detestable of crimes … the town seemed abandoned to the unrestrained license of the half drunken soldiery to gratify their base passions on the unprotected females of both colors.”

One of the chapters in A Legion of Devils is a gripping narrative written by August Conrad, a native of Germany who immigrated to South Carolina in 1859. In January 1865, as Sherman’s army was threatening South Carolina, Conrad traveled to Columbia, thinking that it was a safer place than Charleston, but like so many others, he miscalculated, and soon found himself directly in the path of the enemy. After the war Conrad returned to Germany, where, in 1879, he published a book about the years he spent in South Carolina. The following excerpt from his memoir describes his attempt to rescue a neighbor from a burning house which had been set on fire by Federal soldiers:

“Already the flames were pouring out of the windows. It was a matter of great difficulty to save the old grandmother, who escaped death by fire by a hair’s breadth, and was carried out by two negroes who were kind enough to lend a helping hand. I caught one of the noble heroes by the throat at the moment when he was about to set fire to the bed on which the old lady lay, because I had run thither at her shriek of horror and stopped, just at the right time, this fearful murder. In the struggle, which in view of this incredible crime I did not fear, in the exchange of words which was inevitable, I found out, to my horror, that the beast was a German who could not even speak English. Such a son then has our good Fatherland sent for the extirpation of slavery, but in reality for robbery and murder. And alas, he was not the only one of his race among them who practiced such shameful deeds.”

This new book also includes excerpts from the unpublished diaries of Union officers who participated in another incendiary expedition which has been largely ignored by historians. While Sherman’s army was advancing through South Carolina, moving up toward Columbia, other Federal troops came up out of the Beaufort area, moving north along the coast toward Charleston in a similarly destructive march. One of the units in this force was the 56th New York Infantry Regiment, and the diary of one of its officers, Captain Norris Crossman, recorded the extensive destruction of civilian property in their path. Crossman’s entry for February 22, 1865, for example, reported that “nearly every house on our line of march has been destroyed.” The next day, he noted that Major Smith and a party of 100 men had marched as far as the Ashley River and “destroyed all the buildings along their route.” Almost all the many plantations along the Ashley River, including the beautiful estates of Magnolia and Middleton Place, were looted and burned by the U.S. forces in February 1865. At the same time, Union forces under the command of General E. E. Potter and General Alfred S. Hartwell were raiding the rich plantation country in other parishes outside of Charleston.

Clyde Wilson has commented on the cover of A Legion of Devils: “The war crimes committed by General William T. Sherman and his men against Southern civilians and their means of sustaining life are a huge stain on the American national character. Sherman’s crimes are routinely denied or minimized (by those who don’t actually celebrate them), although they are as heavily documented, from Northern as well as Southern sources, as any event in history. Sherman’s campaign through Georgia and South Carolina is even cited as a brilliant military feat. In fact, it was not a military feat at all. There was very little fighting. It was a massive campaign of terrorism against civilians. It violated international law and hypocritically deviated widely from officially-declared U.S. policy.”

A Legion of Devils adds more very interesting original sources to the published record of a brutal campaign, and includes a timeline documenting most of the significant incidents of January through March 1865, when South Carolina’s home front became a war front for thousands of civilians.