Abraham Lincoln and George Washington stare silently at one another across the reflecting pool on the National Mall in Washington D.C., their paths inextricably linked by the historians who consider both to be the greatest presidents in American history.

One is a monument, a testament to the man and his influence on American history, the other a memorial to the Lincoln legacy, a persistent reminder of the new United States.

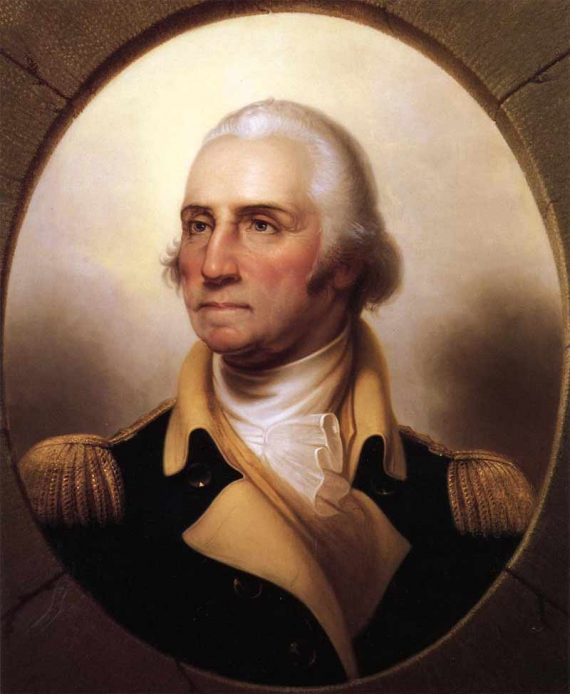

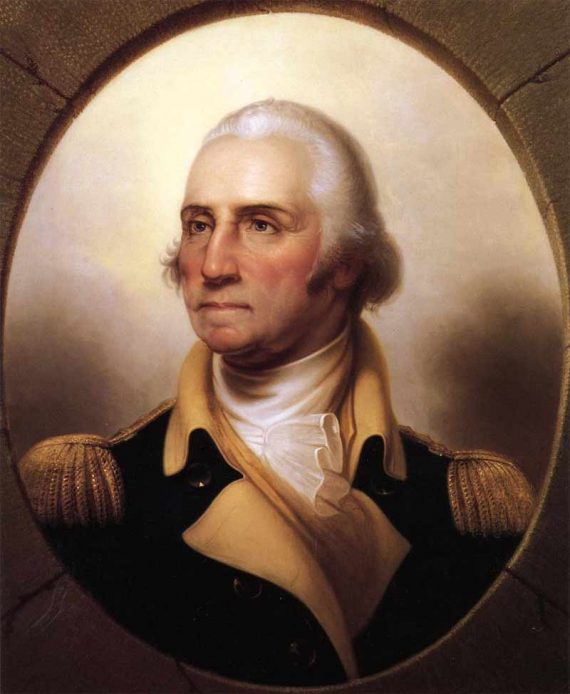

Washington was at one time the symbol of America. Even twenty years after his death, Americans painted their mantles black in mourning for the indispensable man, and many American families hung portraits of both George and Martha Washington in their homes.

Lincoln became a messianic figure, the martyr in a cause to forge a new nation based on the proposition that all men are created equal in an indissoluble union.

“Honest” Abe supplanted Honest George as the quintessential American, and thus two American symbols had been born. One represented the original American order, the other a new America; one conservative and rational, the other revolutionary; one built on the refined ancient constitutions and customs of Western Civilization, the other in a rough-hewn world of log cabins, dirty jokes, foul language, and shifting political sands.

While the monuments of each man may serve as pseudo sentinels guarding the United States Capitol building, America and its legacy cannot be both Washington’s and Lincoln’s. It may seem that both men had much in common, but they, and the symbolic America they represent, are in fact incompatible.

Washington represented the cavalier elite of early American society. He was reared as a gentleman. He was refined, an excellent conversationalist who knew how to dance and flirt properly with women. His father and grandfathers had acquired large Virginia estates, and though they were considered to be middling plantation owners, Washington eventually befriended members of the Fairfax family, the wealthiest landowners in Virginia.

Lincoln was born to a shiftless farmer who lost most of his landholdings due to poor claims, and who preferred to pull up stakes rather than plant roots in one area. Lincoln grew up in the wilderness around rough men and women. He never had any social graces and clumsily interacted with the opposite sex. Lincoln was never reputed to be a fine dancer.

Both men were physically imposing and stood near 6’4”. Reportedly, Lincoln wrestled and split logs, but he never learned how to defend himself in individual combat. Albert Taylor Bledsoe had to teach him how to use a broadsword when Lincoln was challenged to a duel, and his career as a soldier lasted only a few months during the Black Hawk War. Lincoln did not see any action.

Washington hunted and soldiered. He was the best athlete in Virginia, a master horseman, and a real war hero who saved his men from annihilation in 1755 at the Battle of Monongahela, led the American States to their independence in 1783, and was called out of retirement in 1798 to lead American forces against the French in a war that never materialized.

Washington avoided political life by resigning from every political post after the American War for Independence. He could have been president for life, an elected king, but instead chose to retire to Mount Vernon to be a planter and spend time with his family. Washington never campaigned for an office. He was important because of who he was as a man, because of his character. Washington was the greatest man in America before he became president.

Lincoln became a lawyer, represented big business against the little man, consistently sought office, and molded his public statements to gain maximum political effect. Lincoln was important because he was elected to office. He would be forgotten to history if not for the general government in Washington D.C.

Washington faced a “rebellion” on the frontier, and while he eventually agreed to send troops into Western Pennsylvania (at the insistence of Alexander Hamilton), he spent nearly two years exhausting all other means to reach a settlement on the issue. Washington tolerated dissent. He looked the other way when John Jay was burned in effigy and the press excoriated him for supporting the awful Jay’s Treaty with Great Britain in 1794. Even the Whiskey Rebels were treated with kid gloves. The press and elections both remained free.

Lincoln faced an open crisis as president and marched hundreds of thousands of troops into the Southern States to put down a “rebellion” when other options were available. He could have chosen peace but chose war and never negotiated or sought compromise with those who opposed his administration. He rounded up dissenters, shut down newspapers, and barred free elections.

Washington’s Union tolerated differences between the Northern and Southern States, and even Washington himself appealed to their common interests in maintaining a common bond.

Lincoln’s Union forced the will of one section on the other, and his Republican Party openly admitted theirs was a crusade to “forge a new Union” and remake America.

Washington held the Union together through his statesmanship. Lincoln held it together by the bayonet. Washington accepted self-determination. Lincoln waged a war against it.

Lincoln was described as a “gorilla,” “a first rate second rate man,” “an ordinary Western man,” a “fool,” “weak,” and a man of inferior character.

Washington was “First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen,” the “Father of His Country.”

Lincoln inherited a federal republic and created a myth of national supremacy. Washington never pretended to be anything but the president of a federal republic.

The chasm between Washington and Lincoln is larger than the reflecting pool or one spot in a historical presidential ranking.

Lincoln has become America and America is worse for it.