It was pure brag on young Henry Thoreau’s part to say that he had gone to Walden Pond in order “to front only the essential facts of life,” to take a Spartanlike stance against its demands on us, to cut a broad swath and shave close. In point of fact, Thoreau went to Walden to write the book later published as A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, and to gather raw materials for the volume which became his masterpiece. Writing was what most concerned him, as the Journals amply testify, and so it is enough for us to pay homage to that and not remain obsequiously bound to him as a type of pastoral philosopher in the New Eden. A somewhat simplistic social critic, Thoreau’s own quirky presence as an individualist and his forceful grace and clarity as a writer have held us in thrall these many years. To be sure, he was one of a kind. But not the only kind of writer-on-nature we need today.

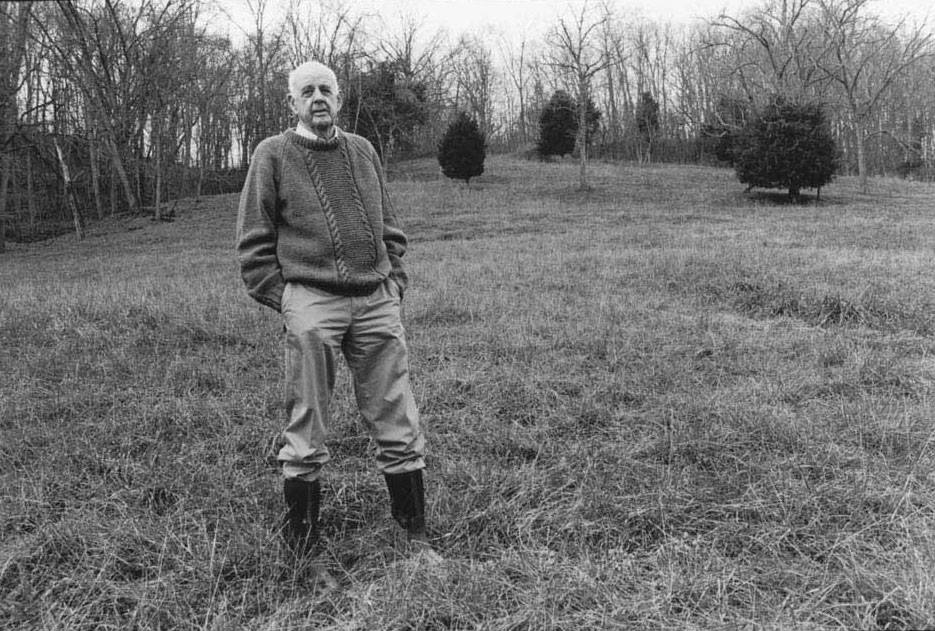

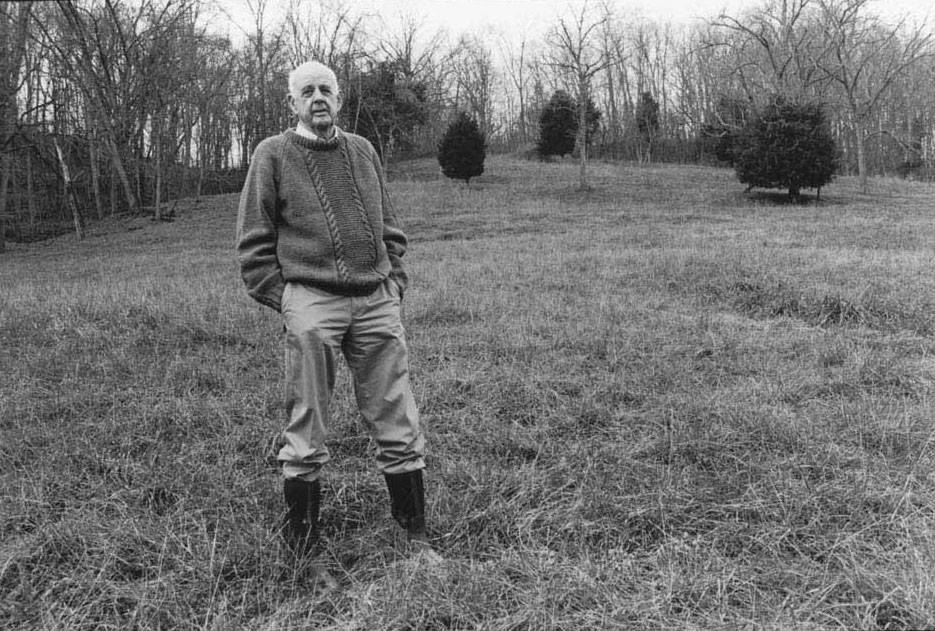

It may seem not only daring but foolhardy to suggest that the contemporary essayist, ecologist, and poet-farmer of Kentucky, Wendell Berry, in at least two important respects may be a far more significant writer than Henry Thoreau of Concord. As writers, Thoreau and Berry have each considered in a major way the question of man’s relationship to nature, and they have written not merely as observers but as participants in the deadly but beautiful life-struggle, a fight for survival which Thoreau saw almost exclusively in microcosm, but which Berry now sees as the compulsion for mankind to endure on this planet.

Something we should question, by the way, is the popular notion that Walden is one of the simplest and most salubrious outdoor books in the English language. In fact, it is full of mythology, specialized natural history, and all kinds of esoteric information on almost every page. It is the sort of book which, if packed away in one’s knapsack for reading material on a walking-tour, would still carry with it the dusty aroma of the library shelf. It is not required that you boast a classical education when reading the books of Wendell Berry. What’s more, having acknowledged Thoreau’s position as a master of American prose, we ought to say just as clearly that Wendell Berry himself is a prose stylist of the first rank. He is also a poet far more skilled in his craft than was Thoreau, one possessed of a quietly lasting power that is sure to survive the noisier reputations of many of his contemporaries.

It is ultimately Thoreau’s obsessive devotion to nature-at once tough, sinewy, and lyrical-that has earned him his reputation as the epitome of the modern ecological movement. The honor more accurately belongs to John Muir, the great western naturalist and mountaineer who founded the Sierra Club in 1892, but who is not read as widely as Thoreau continues to be in this country and abroad. Thoreau climbed only Mount Katahdin, and was deeply shaken by the experience, whereas Muir would have taken Katahdin before breakfast. Thoreau had a way of sometimes missing the point. He had his doubts about the Fitchburg Railroad, for instance, but failed utterly to perceive the seriousness of the irrepressible conflict that was developing, almost precipitously, between unspoiled nature and the industrial revolution. In an embarrassment he hardly lived down for the rest of his life, Thoreau’s most infamous contribution to the ecology of his day was the accidental burning down of large tracts of woodland on the Sadbury River.

More to the point, however, is the further irony that Thoreau’s most notable contribution to anything resembling ecological literature was the late essay “The Succession of Forest Trees” (1860), which remains practically unread by the public at large. Oddly enough, it was at one time presumed by the editors of a supplement to the Oxford English Dictionary (1972) that Thoreau had all but coined the term “ecology” itself, and Thoreauvians everywhere were studiously excited by the new disclosure; but later scholarship revealed that the word he had used instead was “geology.” Such was the extent of Thoreau’s brush with what we know as the ecological movement today. It could not have been otherwise.

However, it is very much otherwise with Wendell Berry. He has produced perhaps the most sensitive and cogently pragmatic body of ecological writing in the United States today. Ecological writing, in Wendell Berry’s hands, has reached the state of art. His books may in time become for everyone the classics which, for many of us, they already are today. Even such specialized volumes as The Unsettling of America (Sierra Club Books, San Francisco, 1977) and The Gift of Good Land (North Point Press, San Francisco, 1981) contain selections that would grace any anthology representing the essay as a literary form. Chapter Seven of The Unsettling of America, “The Body and the Earth,” as well as the title essay itself, is a superb example of analysis and exposition which also serves to encourage our love of nature through a persuasive use of language. The best of Berry’s essays are now available in Recollected Essays: 1965-1980 (North Point Press), a tactile delight in bookmaking itself, and a commendable introduction to the writings in general.

But in order to understand something of the philosophical disposition that makes Wendell Berry a different kind of nature writer from Thoreau, it is necessary to go back to The Long-Legged House (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York, 1969), that unified collection of essays which established Berry’s claim, once and for all, on the attention of Americans in the twentieth century. Compared with Thoreau’s irreducible statements of principle, Berry’s title essay is a declaration of interdependence, renewed and enhanced by the presence of human love itself, and here relocated in the midst of nature. Thoreau’s gregariously inclined solitude, in a jerry-built shack on a parcel of land owned by Ralph Waldo Emerson, would have been for most of us a form of merely eccentric behavior. But nothing, on the other hand, so accentuates the basic relationship between man and woman as the experience of love and companionship in natural surroundings. It is as if one were to become re-attuned to the rhythms of the first creation.

The narrative of Wendell Berry and his wife, Tanya, in a cabin his great-uncle had built on the Kentucky River, is Walden with love. Sexual love. It is what Henry Thoreau might have written if he had eloped with Ellen Sewell of Scituate, and had gone to Walden Pond for a prolonged honeymoon. The very heart of the matter is that Berry has now restored to our concept of nature – and, certainly, to our place in it -that sense of nurturing which is everywhere implicit, when at its best, in the tenderness and concerns of the feminine presence. In both his poetry and prose, Berry sees marriage — or human nature whole – as something irreversibly linked to nature itself:

And there at the Camp, we had around us the elemental world of water and light and earth and air. We felt the presences of the wild creatures, the river, the trees, the stars. Though we had our troubles, we had them in a true perspective. The universe, as we could see any night, is unimaginably large, and mostly empty, and mostly dark. We knew we needed to be together more than we needed to be apart.

The heresy of sexual division is something like the separation of body and soul, and has a direct connection with the current ecological crisis. Nurturing should not be made the exclusive concern of women, Berry says, nor exploitation the exclusive concern of men. “A sexual difference is not a wound,” he adds, “or it need not be; a sexual division is.” Berry regards as a profound error that aspect of the feminist movement which spends its energy arguing the right to be exploiters: “The exploiter is clearly the prototype of the ‘masculine’ man, the wheeler-dealer whose ‘practical’ goals require the sacrifice of flesh, feeling, and principle. The nurturer, on the other hand, has always passed with ease across the boundaries of the so-called sexual roles” (The Unsettling of America). According to Berry, the exploiter rapes the forests, pollutes the streams, and strip-mines the land.

The nearest that Thoreau ever came to witnessing the rape of natural resources was when the ice-cutters descended on frozen Walden Pond to harvest the great blocks of ice, the chippings from which would later cool the summer drinks of the villagers and landlords. Thoreau’s role as self-appointed inspector of snowstorms remains at best a pleasant fraud — like Robert Frost, in our own time, pretending to be a farmer. Meanwhile, it is Berry and the other conservationists who occupy the trenches and who are fighting the good fight on the front lines.

Wendell Berry is the kind of man, moreover, who cannot live without some re-creation in art of the natural beauty he loves so deeply. That is why he is a poet. It is also why he writes a type of poetry which not only pays tribute to nature itself but which, again, restores love to the origins of our most natural condition. No other American poet has written so many good poems about love in the country. A supplementary reading on the subject may be found in the essay “A Secular Pilgrimage” from A Continuous Harmony (1972), and the two books of poetry, The Country of Marriage (1973) and Clearing (1977), all published by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. One cannot know Wendell Berry unless one knows these books as well as the ecological writings, for he is a man whose sources are primarily contemplative.

It is a fitting conjunction of circumstances that out of the region which produced the Southern Agrarians there should now emerge our finest spokesman for an authentic renewal of American culture sourced in love of the land. Is it therefore so shocking to ask whether Wendell Berry may mean more to us than does Henry Thoreau? The case for Berry on ecological grounds is obvious. Just as clearly, Berry is by far Thoreau’s superior in defining that nurturing and complementary love of the feminine principle which he brings at all times to the world of nature and without which the earth itself cannot long endure.