With roots in urban America, the libertarian New Class, which staffs so many of today’s influential think tanks, is disinclined to view the troubles in rural America as a real crisis. This group tends to view a farm as simply another unit of production that, if inefficient, should wither away without public concern—indeed no more deserving of concern than the closing of an unprofitable convenience store or a failing fast-food outlet.

Traditional conservatives, especially Southern conservatives who have their personal and intellectual roots in America’s agrarian past, find the scope and severity of change in rural America to be profoundly alarming and very deserving of public concern. They fear that the winds of economic change that are blowing across rural America will alter the national character. Change has been taking place for some years, of course, and adjustments have been made to it. However, the collapse of world markets for American agricultural products—and the dim likelihood of these being regained any time soon—has accelerated change alarmingly. The visionary planners who promoted the “Green Revolution” succeeded to an extent they and others never imagined. American agricultural assistance to Third World countries has caused their food production to soar. As a result, America has lost major foreign markets, and the country’s domestic agricultural economy has been devastated.

The extent of impending change in rural America has been forecast by the Congressional Office of Technology Assessment which, this past spring, predicted that by the year 2000 some 50,000 large farms will produce 75 percent of America’s food and asserted that half of the nation’s 2.2 million farmers will be gone from the land. This is nothing less than a prediction of an implosion in the heartland of America—a violent collapse inward. If this prediction is correct, it means a massive, new flight from the land and the drying up of an untold number of small towns and cities that serve the needs of rural America. It calls into question the future economic viability of the states characterized as farm states, with unknown consequences for political stability in the farming regions of the country.

It’s hard to argue with the Office of Technology Assessment as regards the shakeout taking place in the farm states. One can’t travel through these states without reading of foreclosures, auctions of farm equipment, the abandonment of farming by longtime farmers, and the failure of banks and other farm-related businesses in towns and cities which traditionally have served farming areas. But one wonders where dispossessed farm people will go in a time when manufacturing areas are wrestling with the problem of displaced industrial workers and the energy states—Louisiana, Oklahoma, Texas and others—face not only massive losses of jobs but crushing deficits running into the billions of dollars. The Congressional Office of Technology Assessment prediction also is one of concentration in agriculture unprecedented in American history. Conservatives, who have developed their political appeal on the basis of urging enlargement of the class of independent businessmen, will find it hard to come to terms with this concentration, especially as it coincides with a new internationalization of American big business that moves offshore a very substantial part of U.S. industrial production. Taking note of this internationalization, Stanley J. Modic, editor of Industry Week, has pointed out that U.S. automakers are planning more joint production ventures with Asian and European manufacturers and that “components are increasingly being made offshore.” American production facilities, which moved out of the old industrial belt in the 1940s, 50s and 60s and which gave a new measure of prosperity and economic balance to rural areas and small towns and small cities, are now being lost as America exports jobs to foreign countries.

In this connection, one of the most unfortunate developments is the enthusiasm with which many state governors, notably governors of Southern states, have sought to persuade Japanese companies to build so-called “transplants” in their states, as though these plants offered economic salvation for their people who have lost work in textile plants and other labor-intensive factories—many of them located in small towns. The “transplants” represent a new form of economic imperialism. The supposed “American content” of these plants usually consists of labor and transportation. Japanese suppliers accompany the major “transplants,” thereby causing additional loss to the economy. The danger in the South is especially acute. The Southern states stand to lose most in the way of American-owned, American-directed plants as their state officials beg for the construction of foreign-owned plants. These officials have learned nothing from the history of the South. The “transplants” provide new pressure to force Americans to accept a global wage.

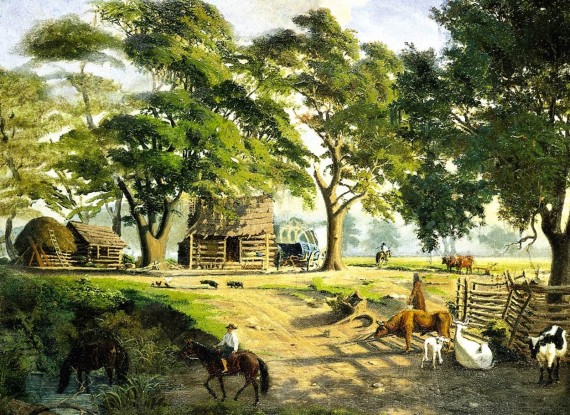

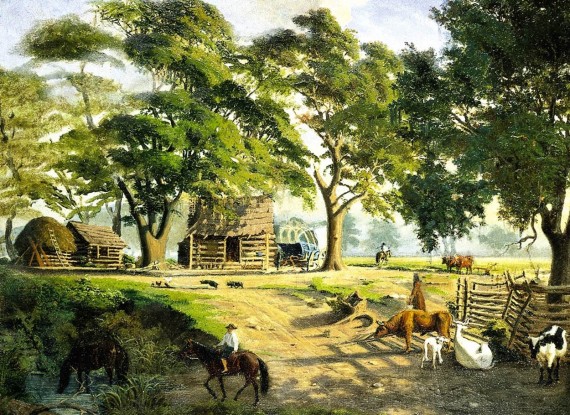

As we ponder these industrial changes and their impact on rural communities and small towns it should be borne in mind that the conservative revival of the past decade placed heavy emphasis upon the importance of the independent small businessman and on the lifestyle associated with rural America—both of which are threatened. In his reelection campaign, President Reagan made use of advertisements that featured a small town-rural American setting. This was the social ideal projected to the American people. “Reagan Country” was supposed to be classic rural America with its belief in hard work, moral virtue and respect for national values. The truth is that rural life and rural themes have an attraction for millions of Americans who live in urban environments. They equate rural life with conservative views of life.

America’s love affair with the rural world was explored in sensitive fashion by William Adams, writing in the Winter 1986 issue of The Georgia Review. Dr. Adams rightly pointed out that rural institutions are “rich with meaning in our collective life and history’.’’ Thus a change in American agriculture is much more than an economic change; it is a change in America’s cultural values. One wonders whether traditional American conservatism will survive if hundreds, perhaps thousands, of small communities are turned into ghost towns between now and the year 2000, as the Office of Technology Assessment suggests.

Rural America always has figured large in the shaping of social idealism in the United States. From the beginning, America was seen in Jeffersonian terms as a nation of small farmers. Though the number of farmers, as a percentage of the population, has steadily declined, the ideal hasn’t been discarded. Millions of urbanized Americans continue to admire the values associated with living on the land. Conservative intellectuals such as Russell Kirk and M.E. Bradford have stressed the fundamental importance of the value of community, which is derived from a settled way of living. These scholars have repeatedly stressed that the American way of life is threatened not only by the collectivist schemes of the Left but by the impersonality of large bureaucratic organizations in the private sector. American values could not endure under a system of Left collectivism; they also could not endure if the little “platoons” of life were eliminated, if small business were extinguished, and large, corporate bureaucracies came to dominate economic life and social organization. This is a Jeffersonian conviction that endures among Americans who share conservative convictions.

Dr. Bradford, in summing up the views of those who cherish the values of rural America, has written that for agrarians “the measure of any economic or political system was its human product. Goods, services and income are, to this way of thinking, subsidiary to the basic cultural consideration, the overall form of life produced.”

What has all this to do with the farm crisis? The answer is that there is much more at stake in the struggle of rural America to survive than mere economics. Dr. Allan C. Carlson, president of the Rockford Institute, commented in 1985 that the “new conservative establishment” as well as the liberal social planners, “is unable to grasp the real situation.” He criticized the outlook of libertarians and praised the viewpoint of the social conservatives, saying the latter “see people, not food, as the principal product of agriculture.” Like the Southern agrarian writers of a half century ago Dr. Carlson said, “We should look at what farmers have meant as well as what they have produced.”

The American people have a cultural stake in rural America and its values. A strong case can be made that they can’t afford the concentration to take place or depopulation to empty our farm states. It should be recalled that the American political system is a geographical system, that is, political power is vested in fixed areas—states—on a permanent basis. The Dakotas and Wyoming—for example—despite their limited populations—have the same weight in the U.S. Senate as California or New York. The people of these thinly populated farm and ranching states have a great interest in making sure that public policy is such that their states don’t become mere shells. Certainly, the representatives of the farm and ranching states—from North Carolina to Montana—will have their say. Indeed, in his essay, Dr. Adams properly raised the question of “the ends of public policy.” Americans always have viewed economic change in terms of larger national goals and purposes, values and ideals. And Congress, as the voice of the people, undoubtedly will ponder whether it wants to let concentration and depopulation take place willy-nilly, without public policy direction.

Public policy with respect to farms and farmers must take into consideration a variety of factors. While much of the world is without sufficient food, and hunger is increasing in a number of Third World countries with socialist-type agricultural systems, the availability of food is taken for granted by urban Americans who aren’t mindful of the problems of the farm states but who expect cheap food in abundance. However, the United States must have intelligent farm policies if this abundance is to continue in the future.

The U.S. unquestionably has adopted mistaken and contradictory farm policies over a long period of years. No one seems to look ahead more than a few years. In World War I. for instance, farmers were urged to expand production to the limit. Demand for food and fiber contracted after the war and the farm depression occurred. The Roosevelt administration began the foolish and costly policy of paying farmers not to plant. The Eisenhower administration continued erroneous production controls with the Soil Bank, which became a laughingstock. In the 1970s, farmers again were urged to achieve maximum production for world markets. These markets have now virtually disappeared.

We don’t have a settled national policy with regard to farming. Moreover, we don’t have a settled national view of the place of farms in our economy and society. Certainly, it’s an error to think of farmers deserving of endless largesse; it also is an error to view a farm as an enterprise that’s exactly the same as other types of business. A farmer can’t get in and out of farming in the manner of a hardware store owner or a restaurant operator. Land has to be cared for over the years; farming requires long-term planning. Non-farmers can’t be trained overnight to become farmers.

Some of these matters are touched on by Dr. Clyde Wilson of the University of South Carolina, writing in the July issue of Chronicles of Culture. He says that there is a “coterie of sophisters and calculators, calling themselves conservatives, who have recently discovered that the production of the staff of life is just another form of corporate enterprise” and that “we must let the ‘marginal’ farmer go to the wall so that the market can wisely redistribute resources.”

As we weigh public policy choices regarding rural America, it is important to bear in mind that we can make those choices that sustain a particular lifestyle and the values associated with it. There isn’t any necessity for the Congress to write farm laws that make certain the concentration and depopulation predicted by the Congressional Office of Technology Assessment. The Legislative Branch need not guarantee a self-fulfilling prophecy. Economics need not have primacy over the wishes of the American people and their vision of the good life. Indeed economics ought not to have primacy in the shaping of the nation’s future as economics is, if not value free, then not the embodiment of the full range of American values.

This is a point that William R. Hawkins of the South Foundation made in Human Events, when he voiced opposition to “an obsession for ‘free market’ economics to the exclusion of all other considerations.” He warned against “heading down the same road as the libertarians…and thus wandering into the same fever swamps.” Indeed he warned that the 1982 congressional elections “should have been sufficient warning not to identify conservatism exclusively with the economy,” saying that conservatism must stress “values people will see as transcending the material conditions of the moment.”

It’s impossible to say precisely how these views and concerns would translate into public policies designed to arrest the concentration and depopulation inherent in the Congressional Office of Technology Assessment forecast. However, conservative legislators have been innovative in recent years in dealing with the problems of depressed inner cities, recommending such systems as “enterprise zones.” There’s no reason to believe that they can’t be equally innovative with respect to rural America, if there is a will to assist the threatened regions. Perhaps the most important and immediate assistance could be offered in the form of action to slow or halt the movement of U.S. industry offshore. The plants that are being located in Mexico, just south of the border, are plants that might well, under different circumstances, be located in Texas, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Virginia or Indiana. Certainly, some of the help must come in terms of research into new crops—agricultural innovation. And in several parts of the country, growers already are producing vegetables, fruits and cereals formerly grown only in such faraway places as Japan and New Zealand. New internal markets are being developed for these crops.

This is one of the happiest developments in the farm states. It offers the best hope of a happy transition to an improved economic situation for many farmers. Diversification is an old word in American agriculture but it is assuming new meaning. The Washington Post reports that state agriculture departments in Iowa. Texas, Michigan and North Dakota, among others, are emphasizing new farm diversification plans. The University of Kentucky is urging tobacco farmers to form vegetable grower cooperatives. In some cases, farmers are being urged to replace tobacco with squash or wheat with flowers (flowers are still being imported into U.S. cities). With the nation producing several billion bushels more com and wheat than it can consume or sell abroad, it’s imperative that diversification be attempted.

The farm states also have been slow to combine their efforts to obtain a significant share of the high tech research in defense fields, especially SDI (Strategic Defense Initiative) research, that will have an important spin-off for new industries in the future. Much more needs to be done by way of educational and research compacts among the farm states so that they share in the technological innovation taking place. All this is essential to a smooth transition into a more secure economic era.

These are a few of the practical possibilities insofar as revitalizing rural America is concerned. Many more opportunities should occur to citizens concerned about safeguarding the rural regions of the nation and maintaining their quality of life. If one thinks in historical terms, one appreciates the fact that the farm states represent important parts of the American spiritual frontier and citadels of American values. Among the notable human products of the rural environment is President Ronald Reagan, who grew up in a small town that serves the surrounding farms. If this world is to wither away and a substantial part of its population is forced into an internal migration, a portion of the American spirit will be lost. It will mean that large regions will cease to have a meaningful, independent life. And one will be compelled to agree with economist John M. Culbertson that “Ours is a land of shrinking expectations.”

For a century people in the farming areas of the South and the West have complained of the concentration of wealth and influence in the Northeast Corridor, which has placed them at a disadvantage.

If there is an economic implosion in the heartland, the worst fears of generations of Americans in these regions will be realized. Indeed we already are witnesses to anger and bitterness in the wake of farm foreclosures and agricultural bank failures, and this undoubtedly would spread and worsen if the farm crisis leads to the massive changes predicted by the Congresssional Office of Technology Assessment. Historically, changes on this scale always have produced severe political unrest. The nation, therefore, has a vital interest in preventing the depopulation from coming to pass in rural America. A measure of change is inevitable in the farming regions but not what amounts to the forced removal of a great part of America’s farm population and the undermining of the economic and social structures which serve them. Farming is one of the three fundamental bases of national wealth—the others being manufacturing and mining. For America’s rural world to go belly up would not only be an economic but a social, cultural, and political disaster. It must not be allowed to happen.

This piece was originally printed in the Fall 1986/Winter 1987 issue of Southern Partisan.