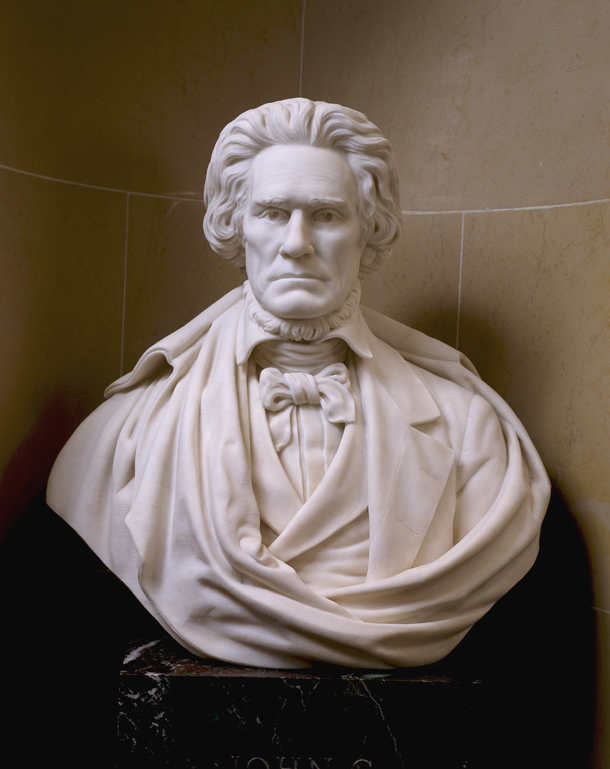

John C. Calhoun was a brilliant political theorist and distinguished politician, and a noted champion of rights for minorities. The importance of his thoughts is reflected both in the doctrine of states’ rights, as well as in relation to the federal system which serves as a textbook example of effective state management. Calhoun was also one of the first to observe that constitutional provisions which set limits on government powers, if open to interpretation, will almost always be in favor of expanding said powers. However, he understood that every society must develop some form of government in order to function. He writes: “Constitution is the contrivance of man, while government is of Divine ordination. Man is left to perfect what the wisdom of the Infinite ordained, as necessary to preserve the race.”[1] Calhoun drew attention to theories and concepts which are essential to American federalism, and justified his political ideology on the basis of its practicality. One of the most interesting issues Calhoun discussed is the concept of concurrent majority and the historical examples he cited to confirm its practicality. In A Disquisition on Government, he gives four examples of such historical applications. Examples of veto institutions, for instance, are the Roman Republic, the Confederation of the Six Nations (Iroquois Confederacy), Poland (Rzeczpospolita Obojga Narodów) and Great Britain. In this text we will examine one of these institutions in particular—that of 17th century Poland. Calhoun does not shy away from the fact that this example seems to be the most extreme application of his theory. Nevertheless, it still possesses convincing argumentative power.

Calhoun writes: “I refer to that of Poland. In this it was carried to such an extreme that, in the election of her kings, the concurrence or acquiescence of every individual of the nobles and gentry present, in an assembly numbering usually from one hundred and fifty to two hundred thousand, was required to make a choice; thus giving to each individual a veto on his election.”[2]

The historical period of Poland that Calhoun refers to concerns the widely used concept of parliamentarism, known at the time as liberum veto (Latin: free I do not allow! or I stop the activity!). Before we discuss the principle itself, it is necessary to outline the historical background. From the years 1569-1795, as a consequence of the Union of Lublin, Poland (in combination with Lithuania) functioned as a federal state called the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The transition of the monarchical system into an increasingly parliamentary nobility democracy took place on the basis of gradual changes and evolution of decision-making powers. At that time, one of the most notable political features of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was that of civil rights, including personal inviolability, freedom of religion, rebellion, i.e. the right of the nobility to rebel against the king, and pacta conventa, i.e. the obligations of the king chosen by free election.

It was in the principle of liberum veto, that Calhoun saw a radical confirmation of his theory. According to this principle, each Member of Parliament taking part in the Diet proceedings had the right to interrupt the proceedings and oppose the proposals for specific resolutions. The purpose of this principle was therefore to achieve unanimity in a federal system. Administratively, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth consisted of a federation of lands represented by deputies, one in a given district.

This principle allowed for the protection of minorities against the dictates of the majority, and therefore expressed Calhoun’s astute idea that votes should not only be counted, but also weighed. The liberum veto made it possible to protect matters of public good from corrupt MPs. In the case of corruption of a large number of MPs, there always remained the possibility that an upstanding, honest member could block any nefarious proposals. Andrzej M. Fredro, then Speaker of the Diet in 1652, considered liberum veto a weapon of the virtuous against the corrupt. Even if the principle of liberum veto was treated as a “protest of an individual” (who could be an agent of foreign influence), this principle still defended political practice against harmful political changes.

If, as Russell Kirk tells us in The Conservative Mind, constitutions are the fruit of national struggles that grow out of community and values, then this proposal of liberum veto, i.e. obtaining a simultaneous majority, will allow us to secure democratic institutions in the state. In this way, apparent contradictions resulting from divergences of interests can be peacefully eliminated. Ultimately, the “section struggle” will be overcome by the so-called “community of benefits”.

Unfortunately, there is a general misunderstanding of liberum veto. There is still debate among Polish historians as to whether the principle of liberum veto was actually an effective form of parliamentary initiative. Calhoun himself was also not without skepticism, as he knew the ultimate fate of the federated states of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. This period ended not with the Commonwealth serving as a beacon of inspiration for the rest of Europe, but rather with the partition of Poland and its disappearance from the map for over a century. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was ultimately dismantled by Russia, Austria and Prussia, and its territory distributed amongst them. Historians have therefore suggested that the fall of the commonwealth must have been related to the chaos allegedly created by this specific form of Polish parliamentarism. It’s worth noting, however, that opposition to this principle was a feature of the “old government” circles. For supporters of a strong monarchy, especially those who demanded the restoration of an absolute monarchy, the principle of liberum veto was a process that only deepened the anarchy of the entire country and weakened the efficiency of the state’s defense structures. A comparison can be drawn between the manner in which Abraham Lincoln, the American father of centralism in practice, would later argue against states’ rights. Lincoln considered the secession of the southern states to be the very essence of anarchy.

In reality, the liberum veto was just a reaction to the overwhelming corruption of the central system, and did not paralyze the state. The real cause lay in the degenerate procedures and institutions left over from monarchical erosion, in which the King distributed property titles at will. Calhoun’s argument concerning liberum veto defends itself. He rightly notes that the Polish state in this political form survived for over 200 years and was – as he writes – “embracing the period of Poland’s greatest power and renown.”[3] He also asserts the Polish state under this form of governance “twice (…) protected Christendom, when in great danger, by defeating the Turks under the walls of Vienna, and permanently arresting thereby the tide of their conquests westward.”[4]

Therefore, it seems reasonable to investigate whether this political principle truthfully contributed to the weakening and eventual collapse of the Polish state. It is worth remembering that this principle was subject to an evolutionary process from a radical to an increasingly limited form. The French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau advised Poles to reduce the principle of liberum veto and limit its use to strictly necessary issues. As a result, the liberum veto was transformed into materiae status, and was taken into account only in matters such as the army or the tax system. Liberum veto was eventually abolished in 1791. Polish historian Mariusz Markiewicz astutely observed that magnates at that time never managed to monopolize power in the state. The Diet dealt with matters of noble privileges, and interrupting its sessions had no major impact on the integrity and functionality of the state. In times of crisis, politicians were able to reach agreements and compromises even among conflicting factions.

Calhoun seems correct when considering the issue of common benefits. Instead of fighting amongst each other, individual interest groups would instead reach a rational compromise. The agreement therefore ensures that each region/section will have the opportunity to shape local structures and institutions according to its own needs. Therefore, this principle was not, if we were to put it into the framework of economic calculation, a zero-sum game. This situation did not go beyond that already visible throughout Europe, in which the dichotomy between the monarchy and the “noble estates” or “interest groups” gradually disappeared.

Although Liberum veto was abolished by the Constitution of May 3 in favor of majority rule, it was instrumental in creating the foundation for direct democracy and the decentralization of power in Poland. While many historians today criticize this principle because of alleged anarchization, there are those that recognize its importance. British historian Norman Davies, author of the monumental work on the history of Poland titled “God’s Playground”, notes that the principle of liberum veto had a civilizational character and was something unique.

The fall of Poland was, perhaps, initiated by completely different factors which had nothing to do with the process of democratization. Instead, the blame could instead be placed on imperial processes emerging in continental Europe, with which the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was no longer able to compete. As Polish political scientist Adam Wielomski notes, the lack of its own aspirations to become one of these emerging empires certainly didn’t do the Commonwealth any favors[5]. The emergence of new military alliances of individual key players in Europe also became increasingly important. It was a time when, according to the European continental tradition, empires began to revive and each sought to be the successor of the fallen Roman Empire. Empires, in accordance with German political scientist Herfried Münkler’s principle of missionality, almost always have asymmetric relationships with their weaker neighbors-states[6]. An additional reason can be attributed to the illegal takeover of power in Poland by a foreign dynasty (at that time, an elective monarchy was in force in Poland) which attacked the local councils. Calhoun understood all these processes perfectly, however he believed that on the basis of political practice, the American Republic would be able to avoid the pitfalls that befell “old Europe”[7]. Unfortunately this was later proven not to be the case. Lincoln’s decisions destroyed this concept, and did not allow a peaceful compromise to be reached in time to prevent the outbreak of civil war. In conclusion, it seems, the partition of Poland and the American Civil War were caused by similar processes. We can broadly describe them as a struggle for power, and creation of an imperial Leviathan.

******************************

[1] Union and Liberty: The Political Philosophy of John C. Calhoun, (ed. R.M. Lance), Fiberty Fund Indianapolis 1992, p. 10.

[2] Ibidem, p.53.

[3] Union and Liberty… op.cit., p. 54.

[4] Ibidem, p. 54.

[5] A. Wielomski, Imperialna Europa. Niemieckie plany podboju i reorganizacji Europy 1871-1945, Fundacja Pro Vita Bona, Warszawa 2024, p. 25.

[6] Per; Ibidem, p. 24.

[7] As a curiosity it should be mentioned that currently the unamity rule and the right of veto of a member state are in force in the modern European Union and it is perhaps the only factor conditioning the internal peace of this confederal structure. Unfortunately, here too the proces is heading towards deepening federalization by abolishing the veto, which may result in a shock to the EU or even its disintegration.

This is important and astute. Thank you for an article of this quality.