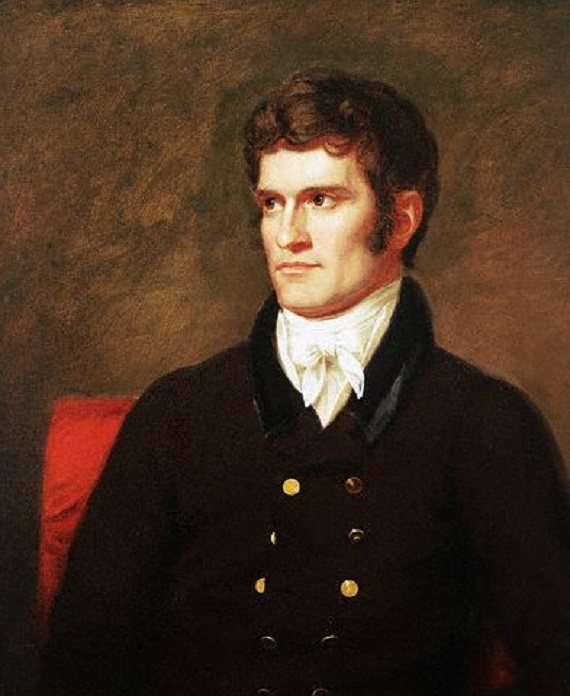

John C. Culhoon. Culhoon is the right pronunciation by the way. John C. Culhoon was an upcountryman. We upcountry people tend to suspect Charlestonians, like Dr. Fleming, of being somewhat haughty and dissipated. Calhoun studied law briefly in Charleston and found a bride here, and he stopped off when he couldn’t avoid it on his way to and from Washington, but he lived in the far western hills as far from Charleston as you could be and still be in South Carolina.

He is buried here, as you may have noted, in the yard of St. Phillips Church. There is a story in that. Having been fortunate in spending nearly every day with this very great man for over 35 years, I have no doubt that he would have preferred to be laid to rest on his own land like Washington, Jefferson, and Jackson.

When his remains were on their way back from Washington City, his family was persuaded to allow him to rest in Charleston temporarily while a suitable monument and final resting place was erected at the Capitol in Columbia. Then the war came and the plans for the monument were never forwarded. In late 1864, when it appeared that Sherman might be headed toward Charleston, the rector and sexton of St. Phillips disinterred the remains and hid them until the war was over. And then there was Reconstruction.

There are, of course, many memorials to Calhoun in Charleston, including the Hiram Powers sculpture in City Hall, which was rescued from the bottom of the sea after a shipwreck, and the monument which you may have seen. The monument was erected in the 1880s, during a time of great poverty in the South, by South Carolina ladies who collected small donations from across the South for over 20 years to make it possible. There is a place not too far away called the “Calhoun Mansion.” It was at one time the residence of one of Calhoun’s grandsons, but has no connection with the statesman.

Having had my fun at the expense of the Lowcountry, it is, of course, fitting that we talk about Calhoun’s Carolina, our history between the Revolution and the War you have already heard about. Out of diverse origins, the South Carolinians of Calhoun’s day created a remarkable unity. In American political history there is nothing like the unity of mind and action that was shown by our gallant little state, as Calhoun called it. During the antebellum era South Carolinians never allowed themselves to be divided by the meaningless contests of national political parties. We were the only state that was able to decide upon and take action on principle without being forced into it by circumstances. We stood alone and unafraid against the powers-that-be in 1832 and won a reduction of the tariff.

In that period, Calhoun was a popular Vice President of the United States. He had been a major American leader since his first speech in the House of Representatives at the age of 29, when he had been recognized, in the words of a leading editor, as “one of those master spirits who leave their stamp on the age in which they live.” He did not hesitate to resign the second highest office in the land to represent and defend South Carolina. Demagogues at the time attributed his act, implausibly, to ambition. They said that when Calhoun took snuff, South Carolina sneezed. Such silliness is still retailed by celebrated historians. In reality, the allegiance was mutual. South Carolina supported the great man that it had produced and he defended the society that had produced him.

Hard as it is to believe today, in the late 1830s the South Carolina legislature refused to accept its share of the so-called “surplus revenue” that was being distributed from the federal treasury to the States on principle—that the money being distributed had been raised by unjust and unconstitutional taxes. That kind of principle no longer exists anywhere in the Union.

But we were, and to some extent still are, at least more than any other state, our own country. We have harbors, rivers, rich soil, forests, factories, hills, plains, great customs and traditions, and fine people—everything we need for a perfectly satisfactory country of our own. Unfortunately, acting in good faith, we made the mistake of joining the Union in 1788, and we have been exploited by stronger outside powers ever since. In our last effort to get out from under them, we mobilized 90 per cent of our male citizens and lost a fourth of them.

Antebellum Charleston had a rich intellectual and artistic culture, much more worthy than Boston/New York centered official opinion has allowed. And South Carolina, in its unity, had genuine diversity. The Catholic Bishop of Charleston, John England, was a leading American prelate and was invited to address the legislature at a time when convents were being destroyed by mobs in Boston and Philadelphia.

When I think of the solidarity of free allegiance within diversity that marked Calhoun’s South Carolina, I think of the clergy of Charleston who met and mingled on free and friendly terms and were at one where the interest of their state was concerned. Bishop England, the Baptist leader Furman, the Methodist bishop Capers, several noted Presbyterian clergymen, the Lutheran pastor John Bachman who was also a world-famous naturalist, noted Episcopalians including the theologian James Warley Miles whose works were read in Europe and who was the master of thirty languages, Rabbi Myers. And perhaps most telling: The Rev. Samuel and Mrs. Caroline Gilman, Unitarians from Massachusetts. His career in Charleston was a steady progress toward orthodoxy, and Caroline, a talented writer, published a defense of the South reply to “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

In the years before the war, any of them could have been seen in Russell’s Bookstore— along with William Gilmore Simms, the poets Henry Timrod and Paul Hamilton Hayne, the first historian of American diplomacy William Henry Trescot, and any of a number of artists and scientific gentlemen who were widely known at the time.

I could talk about Calhoun for the rest of the year, but I am allowed only a few minutes. I could talk about his “Disquisition on Government,” which is as profound an examination of human nature, society, government, and constitutions as ever written by an American and which rests, in part, on the experience of South Carolina in achieving consensus in freedom. I could talk about his understanding of Constitution and Union and efforts to preserve them in their original nature.

But I will instead point to Calhoun’s profound and prophetic statesmanship in less familiar matters—a prime exhibit of republican virtue in which this country was founded and which has long disappeared. Calhoun saw it disappearing long before Lincoln killed it for good. What Calhoun’s words tell us about many aspects of political economy, about questions of war and peace, about the nature and destiny of the American experiment, might persuade that he is the ideal republican statesman produced and upheld by the ideal republic that was South Carolina. And what he has to say is as relevant at this moment as it was when he spoke.

© Clyde N. Wilson. May not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission.

SOURCE: Remarks at the John Randolph Club Annual Meeting December 9 & 10, 2005 in Charleston, South Carolina.