Antebellum California secession is a little known topic, but the Southern portion of the State nearly broke free from Northern California in the years just before the outbreak of war in 1861.

California gained statehood in 1850 with a Senate vote of 34 ayes and 18 nays and a House vote of 156 ayes to 56 nays with Jeremiah Clemens of Alabama recording: “The admission of California was first recommended by a Southern Democratic President…..When the bill was finally passed, eight of the fifteen Southern States furnished votes for it. Kentucky gave seven out of ten, and Tennessee seven out of eleven in the House of Representatives.”[1] Closing his argument with, “in the case of California…..the South passed that bill, and if it robs us of any right, we robbed ourselves. There was not an abolitionist or free soiler in either branch of Congress who voted for it. There were but two Southern Senators who voted against it.”[2]

However the years from the California Constitutional Convention of 1848/9 through the end of the war between the states, Southern California from the pueblo’s of Los Angeles attempted multiple times to split the State.[3] When the attempted filibuster to prevent statehood failed, they turned to secession. These secession attempts were led by Californio’s such as Pio Pico, Andres Pico, Jose Antonio Carrillo, Thomas Avila Sanchez and other war heroes of San Pasqual.[4] Southern California’s secession attempts were but another example in a long line of American secession movements.[5] Los Angeles showed the world at the tail end of a global period of revolution that not only was slavery a smoke screen for “the ignorant masses” as pointed out by Otto Von Bismark years later, [6] but that the Sons of the South and the Sons of Mexico shared a common goal: freedom from the New England imperialism taking place on the North American continent.

California and its beautiful untapped resources would be engulfed in epochs of changing power that would define its culture, tradition, and its people’s inability to be conquered by any rapidly centralizing government. The phrase ‘Abajo Los Americanos!’ would roll off the tongues of every real citizen of Southern California until the last confederate would lay his head in the fertile soil of Orange County during the first decade of the twentieth century. The attempted landing of Fredrick Jackson Turner’s proverbial fault line on the coastal shores, where the California Constitutional convention would meet, caused the radically different demographic of constituents just a few short hours down what is now known as Pacific Coast highway to fundamentally beat back the growing progression of nationalism that was brought with western conquest through sectional conflict and attempted secession. From the pueblo that became Los Angeles, the pages of the famed resolutions of Kentucky and Virginia of 1798/99 found a defense, “Reserving each state to itself, the residual mass of right to their own self government; and, that whensoever the General Government assumes un-delegated powers, its acts are un-authoritative, void, and of no force; that to this compact each state acceded as a state, and is an integral party…”[7]

Within two years of the admission of California into the Union, the Angelenos and the rest of Alta California were already working towards division. On October 28, 1851, the Semi-Weekly Camden Journal announced that a, “Southern Address, by a Southern Committee at San Jose, proposes that call of a convention, to take place at Santa Barbara, on the third Monday of October.”[8] The counties that advocated this proposed division “presented a line of territory that included, San Francisco, Contra Costa, Santa Clara, San Joaquin, Calaveras, Tuolumne, Mariposa, Santa Cruz, Monterey, Santa Barbara, San Louis Obispo, Los Angeles, and San Diego.”[9] The journey in protest of admission to the United States started February 10, 1850, in Los Angeles. A series of resolutions addressed to the Congress of the United States and drafted by a committee elected at Los Angeles had one goal in mind, to “sign a petition against the admission of California with its proposed boundaries, and, in effect, to leave the southern part of the state as a territory.”[10]

By August, 1851, the plans had taken form. According to Historian William Henry Ellison, “In Los Angeles County, all candidates for the legislature pledged themselves to use their efforts to obtain a division of the state. The same test was to be made in other counties.”[11] San Diego unanimously “determined to exert themselves to that utmost of their peaceable and honorable means to effect a proper division of the State.” The resolutions cited among other things taxes and transportation. Stating that:

“the difficulties and cost of transportation to the markets of the North being so great, that all profits are consumed, and the labor and capital of the people of the South rendered non productive beyond a bare subsistence; thus creating a great difference between the value of a dollar to the South and the Value of the same dollar in the North, consequently any revenue law which levels the same percent upon the dollars, must fall heavier upon the lower than upon the upper country. This being the case, while the latter may sustain themselves under the burden of heavy taxation, the former will be oppressed, and in the end, absolutely impoverished…..while this is humiliating, it no way releases him from the burden with which he is now, and must continue to be oppressed.”[12]

The Californios who once held prominence in the state now faced a heavy tax burden. By the time California Governor John McDougal gave his inaugural address in 1851, a section of the State with only twelve representatives to the legislature paid $246,247.71 in taxes, while the other section with forty-four representatives to the legislature paid only $21,253.66 to the treasury during the last fiscal year.[14] A California historian would eloquently claim, “with American statehood came newfangled American ideas like property taxes, which weighed heavily on the families who measure their land in thousands of acres.”[15]

The constitution of 1849 was drafted with little or no restrictions on the power to tax, and with uneven representation, Southern Californians paid more than their “fair share.”[16] Each year the legislature meet in the northern country of California, the southern section brought a proposal for a State convention to rectify the problem, but this did not materialize until 1879.

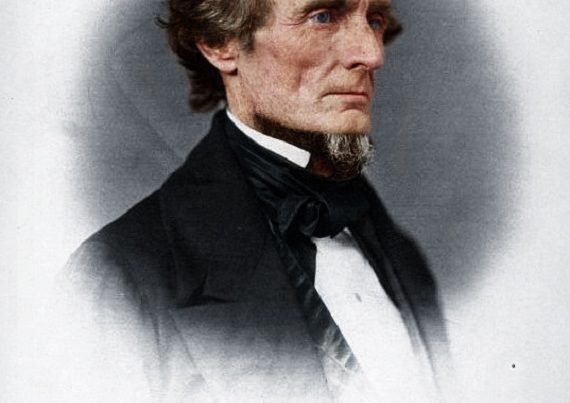

As a result, the people of Los Angeles presented another plan. When the Assembly meet the third day of January, 1859, Assemblyman William F. Watkins introduced Bill 174 entitled, ‘an act to authorized the citizens of the State of California, residing north of the fortieth degree of north latitude, to withdraw from the State of California, and organized a separate Government.’[17] California Brigadier General Andres Pico, [18] brother of former Governor Pio Pico, suggested that it be referred to the county delegates,[19] to which the counties carried a two-thirds vote. Pico claimed the differences between “Climate, Soil, and productions of the South and the North, the dissimilarity of the people in language, manners, customs, and interest, and the separateness of the two sections made by geographical conditions.”[20] The people of California voted to accept the proposal 2457 for and 828 against. Northern California had finally agreed to let the Old California residents of the Southern Section go. This was natural considering that the Northern country had already admitted that, “The southern section was the most sparsely represented, and, in proportion to their means, the most heavily taxed portion of the state, while in the disposition of the general officers, neither party deemed the South worth conciliating even by a nomination.”[21]

The following year, interim Governor and California State Senator Milton S. Latham submitted both the California secession bill and his thoughts on the proposal to President James Buchanan. Latham stated that, “As the people of the State are deeply interested in any action Congress may take in this matter, and as I may soon be required, as a Senator, to urge or oppose the formation of a new government for these counties.”[22] Latham, in his letter to Buchanan, would argue that,

“The origin of this act is to be found in the dissatisfaction of the mass of people, in the southern counties of this State, with the expense of State Government. They are an agricultural people, thinly scattered over a large extent of country. They complain that the taxes collected in the mining region; that the policy of the State, hitherto, having been to exempt mining claims from taxation, and the mining population being migratory in its character, and hence contributing but little to the State revenue in proportion to their population, they are unjustly burdened; and that there is no remedy, save in a separation from the other portion of the State. In short, that the Union of southern and northern California is unnatural. The people of Southern California preferred a territorial to a State form of government. But, yielding their preferences, they made common cause with their brethren of the North, in the adoption of our present constitution, though from that time forward they seem to have regretted the step.”[23]

Latham argued this was legal because it did not violate article four, section three of the Federal Constitution, and because the people of the State approved the move in a referendum. He also suggested, “If a state consents that a portion of its territory be severed, I see no reason why Congress may not permit that territory to be erected into a territorial government if its inhabitants so desire.”[24]

Unfortunately, Yankee transplants in California would urge the Senators and Representatives from California as well as the rest of Congress to oppose the separation. The bill eventually got caught up in the heat of secession and the question of slavery extension in the new territories and was effectively filibustered out of existence. Though it could be said that, “In the Senate…..the questions involved…reported favorably a bill providing for the segregation of the southern counties in accordance with their vote.”[25]

[1] Jeremiah Clemens. 1852. The Sumter Banner: Mr. Clemens of Alabama Speech. March 16, 1852. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn86053240/1852-03-16/ed-1/?st=gallery

[2] Jeremiah Clemens. 1852. The Sumter Banner: Mr. Clemens of Alabama Speech. March 16, 1852. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn86053240/1852-03-16/ed-1/?st=gallery

[3] John Ross Browne. 1850. Report of the Debates in Convention of California on the Formation of the State Constitution, In September and October, 1849. Pp. 1 – 60. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/reportdebatesin01browgoog/page/n4/mode/2up

[4] William Henry Ellison. 1913. The Movement for State Division in California, 1849 – 1860. The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. Vol. 17. No. 2. Pp. 117 – 118

[5] An Anglo-Californian. 1861. The National Crisis: A letter to the Honorable Milton S. Latham, Senator for California in Washington. February 4, 1861. Pp.1 – 21

[6] Major General Count Cherep-Spiridovich. 2000. The Secret World Government or “The Hidden Hand”: The Unrevealed in History. First Edition. Book Tree Publishing. Pp. 180

[7] Thomas Jefferson. 1798/99. The Kentucky Resolutions.

[8] The Semi-Weekly Camden Journal: Division of California. Camden, South Carolina. October 28, 1851. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn93067976/1851-10-28/ed-1/?sp=2&q=the+Los+Angeles+Star&r=0.677,0.069,0.421,0.279,0

[9] William Henry Ellison. 1913. The Movement for State Division in California, 1849 – 1860. The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. Vol. 17. No. 2. Pp. 105 – 106

[10] Ibid. 106

[11] Ibid. 111

[12] The Semi-Weekly Camden Journal: Division of California. Camden, South Carolina. October 28, 1851. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn93067976/1851-10-28/ed-1/? sp=2&q=the+Los+Angeles+Star&r=0.677,0.069,0.421,0.279,0

[13] William Henry Ellison. 1913. The Movement for State Division in California, 1849 – 1860. The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. Vol. 17. No. 2. Pp. 117 – 118

[14] Ibid. 118

[15] Phil Brigandi. 2017. Orange County Chronicles. Pp.

[16] Noel Sargent. 1917. The California Constitutional Convention of 1878-9. California Law Review. Vol. 6. No. 1. Pp. 1 – 5

[17] John O’Meara. 1859. Journal of the House of Assembly of California at the tenth session of the legislature, begun on The third day of January, 1859, and ended on the nineteenth day of April, 1859, at the City of Sacramento. John O’Meara, State Printer. Pp. 291. Retrieved from https://clerk.assembly.ca.gov/sites/clerk.assembly.ca.gov/files/archive/DailyJournal/1859/Volumes 1859_jnl.PDF

[18] Daniel Lynch. 2014. Southern California Chivalry: Southerners, Californios, and the Forging of an unlikely Alliance. California History. Vol. 91. No. 3. Pp. 61

[19] Ibid. 553

[20] William Henry Ellison. 1913. The Movement for State Division in California, 1849 – 1860. The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. Vol. 17. No. 2. Pp 130

[21] William Henry Ellison. 1913. The Movement for State Division in California, 1849 – 1860. The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. Vol. 17. No. 2. Pp. 112

[22] Milton S. Latham. 1860. Journal of the House of Assembly of California, at the Eleventh session of the Legislature, begun on The second day of January, 1860, and ended on the thirtieth day of April, 1860, at the city of Sacramento:Communication of Governor Latham. Pp. 125 – 126. C.T. Botts, State Printer. Retrieved from https://clerk.assembly.ca.gov/sites/clerk.assembly.ca.gov/files/archive/DailyJournal/1860/Volumes/1860_jnl.PDF

[23] Milton S. Latham. 1860. Journal of the House of Assembly of California, at the Eleventh session of the Legislature, begun on The second day of January, 1860, and ended on the thirtieth day of April, 1860, at the city of Sacramento:Communication of Governor Latham. Pp. 125 – 126. C.T. Botts, State Printer. Retrieved from https://clerk.assembly.ca.gov/sites/clerk.assembly.ca.gov/files/archive/DailyJournal/1860/Volumes/1860_jnl.PDF

[24] Ibid. 127

[25] Ibid. 136 – 137

One Comment