In November 1970, Lt. William Calley (a Florida native born in 1943) went on trial for his life. He was being court-martialed by the U.S. military for his participation in the My Lai Massacre and was accused of killing twenty-two civilians. Even though twenty-six officers participated and an estimated five hundred South Vietnamese were killed, Calley was the only man tried and convicted.

The debate surrounding Calley’s actions intensified after politicians became involved. Georgia governor and future President Jimmy Carter instituted “American Fighting Man’s Day,” and asked Georgians to drive for a week with their headlights on in support of Calley. Alabama governor George Wallace visited Calley in the stockade and personally requested that President Nixon issue a pardon. Edgar Whitcomb, the governor of Indiana at the time, asked that all state flags be flown at half-staff for Calley.

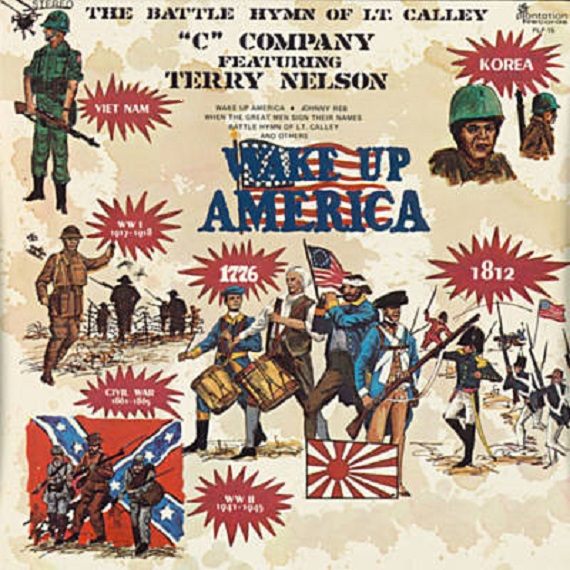

Musicians around the country also came to Calley’s aid and wrote songs in his defense. “Big Bill” Johnson wrote a song called Set Lt. Calley Free, which stated “We’re a sick, sick society, we’ve nailed Lt. Calley to a tree…We Americans are tired of a war that can’t be won, where a soldier is charged with murder if he uses his gun.” Another song by C Company, featuring Terry Nelson, titled The Battle Hymn of Lt. Calley features lyrics like “I’ve seen my buddies ambushed…all the rules are broken…it’s hard to judge the enemy”. The artist also criticised the anti-war movement, claiming that those “marching in the street…were helping our defeat”. Nelson Truehart wrote a song called Morning in My Lai, which asked Americans not to judge Calley because “after all, he’s just fighting for you and me.”

While most of the songs were country and performed by southerners, many songs of multiple genres went beyond defending Calley and portrayed him as a scapegoat. Even anti-war songs like Hang Lt. Calley and The Cry of My Lai were more critical of the government than they were Calley.

The bigger question is why so many Americans, particularly southerners, supported Calley? If southerners had once been victims of total war, how could the region defend Calley’s actions? In the book Lt. Calley: His Own Story, Calley stated the following regarding the parallels between Vietnam and The “Civil” War:

I say this: If this were a hundred years ago, if I were a Union lieutenant and if Sherman told me, ‘Kill everyone in Atlanta,’ I guarantee I would have to. I once got a letter on My Lai saying, ‘My God! Why are the Yankees upset?’ It is said in the Civil War, the Yankees were up against guerillas too. All the South’s men, women, and children were out to defeat them…The same as Vietnam: the people became guerillas then. And used unconventional warfare: but the North wasn’t about to sit in its trenches worrying…[Sherman] ordered his men to burn, to kill, and as soldiers say: to rape, pillage, and plunder the South. And there was no stopping him. The tactic worked…If you’re a Yankee, you’ll tell me, ‘Sherman’s great,’ and you’ll put a statue of Sherman in Central Park. As for me, I’d hate to see a monument to Calley’s March to the Sea.

The fact is that Calley had just been following orders. There had been increasing pressure from commanders for higher kill counts, and his exact orders when entering My Lai were to search and destroy. No American volunteered or was drafted for the purpose of killing civilians. In fact, when Calley and his men first arrived, they tried very hard to win over the South Vietnamese. As time went on, they noticed the locals were purposefully not helping them fight the Vietcong. Soldiers faced violence from men, women, and children of all ages during combat. The Vietcong were also heinously murdering captured soldiers. On one occasion, Calley recalled a soldier who had been captured, skinned alive, and bathed in a salt solution. The next day, they found the man’s skin ripped from his body and strung on a pole, with his penis having also been cut off.

Calley realized that he was not fighting a tangible enemy, but an ideology. Before being called back to the U.S. for his court-martial, Calley volunteered to become an S-5. This was a special unit that helped South Vietnamese harvest crops, construct housing, repair infrastructure, teach sanitation, and give education. Calley was beginning to see that it would not be so easy to win over the South Vietnamese, even as a non-combatant. He stated “a farmer in Asia doesn’t want to be any nuclear scientist. Or a lawyer, or to use light switches or air conditioners, or to own some commercial crap. And worry about the Sears bill: no, a utopia to a Vietnamese farmer is a little land and a healthy pig.”

Soldiers and Americans at home were beginning to realize the Vietnam War might be unwinnable. By 1969, a Senate committee found that three hundred thousand civilians were killed, five hundred thousand more had been wounded, and four million people were made into refugees. It seems absurd that with all the carnage, only Lt. Calley was held responsible for war crimes. The question remains: why were southerners such staunch defenders of Calley? Had Calley and the south become so reconstructed, that they refused to question the government?

The answer is that the south is and always has been the spirit of America. Southerners, in general, are intensely patriotic people. In Calley, they saw not a scapegoat, but a reflection of themselves: a good old boy torn apart by the ravages of war. In addition, most people (not just southerners) sympathized with Calley. Many of the soldiers involved testified in his favor, and Calley was eventually transferred to house arrest by President Nixon. The Journal of American History shows that after Calley’s conviction, the White House received over five thousand telegrams, with a ratio of 100 to 1 in favor of leniency. A telephone survey of the American public also showed that 79 percent disagreed with the verdict, with 81 percent believing that the life sentence Calley had received was too harsh, and 69 percent believing Calley was a designated scapegoat.

The Vietnam Veteran has been constantly reinterpreted. At the height of the war, soldiers were returning home only to be spat on and called “baby killers,” and with the rise of PTSD during Vietnam, many of the soldiers were being portrayed as suicidal and unstable. By the 1980s, perceptions of the Vietnam vet had changed again; while awarding a Congressional Medal of Honor to Roy Benavidez, Ronald Reagan stated: “Several years [ago], we brought home a group of American fighting men who obeyed their country’s call and fought as bravely and as well as any Americans in our history. They came home without a victory not because they had been defeated but because they had been denied permission to win.” Since then, we have seen the image of the Vietnam vet transform into gritty American heroes like those portrayed by Sylvester Stallone and Chuck Norris in movies like Missing in Action, Uncommon Valor, and Rambo–all of which were intended to make war fashionable again.

The time has come to reconsider Lt. William Calley. He may not have been a saint, but he was following orders and certainly was not the only man who killed civilians. While he does not deserve a monument, his actions are important because they raise questions about our military and government. Does the United States only involve itself in just wars? What are the real, long term consequences of Sherman’s march and the total war tactics of The “Civil” War? Will the United States ever stop fighting wars and rebuilding foreign countries? These are just a few major points that make Calley’s story important from a historic perspective.

Listen to “Big Bill” Johnson’s Set Lt. Calley Free: