Introduction to Chronicles of the South: In Justice to So Fine a Country

“The South” is a Problem. A Big Problem. This has been true at least since the 1790s when Mr. Jefferson and his friends rallied to put the kibosh—only temporarily, alas—on New England’s attempt to reinterpret the new Constitution and set up a central government powerful enough to enforce its economic and cultural domination. As Mr. Jefferson wrote at the time, “It is true we are completely under the saddle of Massachusetts and Connecticut, and that they ride us very hard, cruelly insulting our feelings, as well as exhausting our strength and substance.”

Actually, the sources of the Problem can be found even earlier. Richard M. Weaver’s last work, unfinished, was an American Plutarch, viewing American history through differing Northern and Southern figures—Hayne and Webster, Randolph and Thoreau, etc. In his “Two Diarists” Weaver laid side by side the early eighteenth century records of Colonel William Byrd II of Virginia and the Reverend Mr. Cotton Mather of Massachusetts. Allowing that both were Englishmen born in the North American colonies, the two men lived in different mental universes. While Byrd was writing in his diary about his good times, even the guilty ones, his wide reading, his socialising with cordial neighbours, his love of nature, and his adventures in the wilderness, Mather was secretly recording the evil hearts of his associates, the failure of the world to fully recognise his merit, and complaints and lectures to God about the injustice of His insufficient good favour. Mather was too provincial and too preoccupied with himself to notice the South, but if he had, you could be sure he would have seen a Big Problem. You can almost see the War Between the States laid out there a century and a half in advance.

Be that as it may, we have in American history, as viewed by the enlightened, a long-standing Problem, the South. One time the problem got so big that it had to be put down the hard way because of its stupid obstruction of banks, tariffs, and other manifestations of state capitalism and legal graft that were required for the divinely-ordainerd progress of the “nation.” Thereafter, well into the 20th century, respectable Republicans regarded the South as an excellent place for cheap resources and cheap labour, but a hopelessly benighted region that was likely to produce dangerous wild-eyed Populists and New Dealers.

More recent but already once more a fixed and pervasive national consensus, there is the reincarnated view that “the South” is the dark repository of all that is retrograde and evil, an obstacle to America’s destined perfection. My classic example, among thousands, is the Ivy League intellectual who proclaimed that an increase of violence in America is a result of the spread of “the Southern gun culture.” This bit of wisdom was put forward at the same time we were hearing of Timothy McVeigh of New York and the U.S. Army, the Unabomber of Harvard and Berkeley, and the Columbine shooters— none of whom were Southern and none of whom except the last used guns. You see, if there are things wrong, it can always be traced to something seeping out of that pit of evil unAmericanism, the South.

Since “the South” has at times served as the whipping boy of both conservatives and liberals, might we begin to suspect that there is something going on here that has more to do with the eye of the beholder than it does with the thing beheld? Might we have at work something some scholars have described as “the internal oriental”? The “internal oriental” is a group within a society that is shunned as deviant and alien and thus becomes very useful for the society’s pleasing self-perception of its own identity and virtue.

In a recent twist on the national consensus it is widely announced that “the South” does not really exist except as a little corner of racism and treason with no claim to a real identity, historically, culturally, or otherwise; get rid of slavery and segregation and there is no such thing as “the South.” This is something new and quite curious. Only a few decades ago Confederate flags were commonly seen among American fighting men both in reality and in Hollywood’s rendering of reality, and the “traitor” Lee was viewed as a treasure for all Americans. Southerners were seen as different and perhaps a little quaint, but tolerated as real Americans. Now “the South” is only part of the forward-looking Sunbelt, and the U.S. Marines, once an almost Southern organisation, have criminalised Confederate symbols.

We can leave aside the intellectual (or rather pseudo-intellectual) past-time of defining “the South.” Most of the definitions one sees aredesigned to minimize and denigrate. Any good thing about the South is not really “the South” but only “America.” Anything you don’t like is “Southern” and not really “American.” There are even those who argue that while the South does not really exist it is still a Big Problem, what they call an unwholesome “Lost Cause Myth” believed by the backward and deluded. Such “intellectuals” leave unexplained what any sensible observer can see: there is some kinship between Thomas Fleming’s Low Country South Carolina and J. Evetts Haley’s Texan cattle kingdom that is not explained by climate and geography. Let’s just agree that there is a certain American cultural and historical heritage that still manifests itself in numerous ways and constitutes something quite real that has always been called “the South.” It may be true that the South, though having some tangible manifestations, is mostly a state of mind. A state of mind is not the same thing as a “myth” (a term badly misunderstood by the advocates of the “Lost Cause Myth”). A state of mind is the realest thing there is because it structures what we see in the “real” world so beloved of materialists. Ideas have consequences.

The South is something not only quite real but an inescapable component of the American past and the American present. A very large component, whether measured by territory, population, historic importance, literature and music, statesmanship, military skill and valour, or the deep substance of everyday American life and manners. And I don’t mean just NASCAR and “country music” which are symptoms, not the substance. The South, however you want to define it, is deep in the ancestral blood of the Midwest and the West. Not only that, but the South has always had a strong appeal to some of the finer spirits born outside its territorial bounds. Many of the thousands who have moved to “the Sunbelt” from colder climes in recent years are carpetbaggers, but a lot of them are self-chosen (and welcome) additions to the Southern folk.

Chronicles, almost alone among American journals, has amazingly and refreshingly avoided all the fashionable pseudo-intellectual games and rites of exorcism and treated us Southern people like any other people. It has honoured the simple proposition that Dixie is real, is something worth looking at plainly, has a right to speak for itself, and perhaps even deserves a little appreciation. The fruits of such proceeding can be seen in this rich selection of articles and writers from several decades.

In 1920 H.L. Mencken’s well-known essay “The Sahara of the Bozart” appeared in book form, opining that the Southern region of the United States was as empty of culture as the great African desert. Mencken headed his scandalous piece with lines by J. Gordon Coogler, who he described as “the last bard of Dixie”:

Alas, for the South! Her books have grown fewer—

She never was much given to literature

One might spare a bit of sympathy for Coogler, who was damned to that once common American vocation of churning out every day verses to amuse or inspire any fool with a nickel to buy a newspaper. Also, it is seldom noted that Mencken’s disdain for the New South was in part a result of his admiration for the Old South. In other essays he deplored the outcome of the War Between the States as the victory of Babbitts over gentlemen, said that the Gettysburg Address was a lie, though a pretty one, and pointed out that his Baltimore was less corrupt than other big cities because of the influence of honourable ex-Confederates who were superior to the wardheelers and grafters who ran most American cities.

Mencken, as usual, was exaggerating when he exposed the great Southern Sahara. Thomas Nelson Page, Mary Johnston, and Elizabeth Maddox Roberts, all children of the Confederacy, and other creditable Southern writers were well-established at the time among the Northern magazine and book-reading public. Not in the category of great art certainly, but literature none the less: the novel St. Elmo by the Mobile lady and former Confederate nurse Augusta Jane Evans Wilson had not long before passed Uncle Tom’s Cabin as the all-time international best seller, and Thomas Dixon’s turgid books had been turned by D.W. Griffith into the pioneer masterpiece of American cinema, “The Birth of a Nation.” (Both Dixon and Griffith also were Confederate children.)

More pertinently, when Mencken’s animadversions appeared, there had begun to gather at Nashville a group of writers whose talent would soon astonish the world, and who were partly energised by rejection of Mencken’s cruel treatment of the Christian faith of Southern plain folk at the Scopes “Monkey Trial.” The Charleston Poetry Society was beginning to nourish DuBose Heyward and others, Margaret Mitchell would soon be stuffing her sofa in Atlanta with the manuscript of “Gone with the Wind,” and William Faulkner was feeling his way into the literary mission that would make his little postage stamp of country in Mississippi into a universal gift to mankind.

Today, presumably nobody would venture to declare the South barren of great writers,though the New York literati still like to condescend to the peasants (nervously but with chutzpah). But, tell me, where other than in the journal modestly subtitled “A Magazine of American Culture” and under the aegis of Thomas Fleming would you find casually rubbing elbows such giants as Andrew Lytle (by interview), Donald Davidson, Walker Percy, Wendell Berry, George Garrett, and Fred Chappell? Perhaps that subtitle ought to read “THE Magazine of American Culture.”

Generally the Southern writers allowed into “mainstream” publications are either those who have made a career out of libelling the home folks or those too important to be ignored. Amazingly and refreshingly, Chronicles has not only treated Southern subjects abundantly and fairly, it has welcomed many Southern writers who are not among the great but who have something to say and can say it well—Thomas Landess, J.O. Tate, Katherine Dalton, Aaron Wolfe, William Murchison, John Shelton Reed, Jack Trotter, Egon Tausch, and others. A selection of the fruitful results of editorial courage and magnanimity is in your hands.

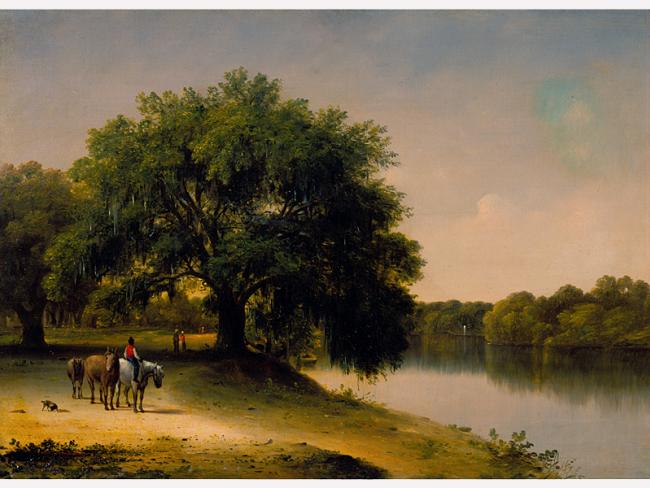

Introduction to Chronicles of the South: Garden of the Beaux Arts

The sociologist and one-time Chronicles columnist John Shelton Reed does not regard the South as a Big Problem, but rather as something to be objectively described like any other human phenomenon and maybe even appreciated a little bit. (And where else but Chronicles would you expect to find the only real live sociologist in captivity who can write well and has a sense of humour?)

In The Enduring South Reed painstakingly quantified a lot of data about behaviour and attitudes to establish that, yes indeed, there are such things as Southerners who can be identified as distinct from the baseline of regular Americans. The difference is not absolute but is statistically significant. Reed found the difference most identifiable in three areas.

Southerners adhere to the basic tenets of orthodox Christian belief more than other Americans, even the general run of Catholics. Indeed, the South is the only Protestant society remaining in the world that is not post-Christian.

Second, Southerners are more family and locally oriented. They are more likely to name their children after Granpaw or somebody else close by than to adopt some trendy name; more interested in their own community than in celebrities or those national and international “issues” which many Americans mistakenly believe they understand and have some control over.

Thirdly, Southerners have a different attitude towards the appropriate uses of violence. Put shortly, this means that in the South you are more likely to be murdered by someone you know and elsewhere by a stranger. This characteristic also suggests a persistence of old fashioned sex roles and a bit of chivalry, familiarity with firearms, and a willingness to resort to self-defense before calling in the police.

I can add some other distinctions. The South remains not only the most socially conservative but the most politically conservative region of the United States. It is the only region that has continued for decades to vote Congressional majorities against every leftist measure adopted, right up to the Obama administration’s “health care plan.” This remains true even though districts have been gerrymandered in favour of minority candidates and constituencies and Country Club Republicans have appeared in droves.

Another Southern distinction is of fairly recent origin. The South is the only part of the United States in which a majority of African Americans say that they feel at home, and the only part with a net in-migration of African Americans. The significance of this phenomenon will, of course, never be acknowledged by the political class, the media, the educational establishment, or enlightened opinion. They have for too great an investment in self-righteousness, the self-love confirmed by having the South to correct. Old habits die hard, especially if they make you feel superior.

Most certainly the South has changed lately, but it has not yet disappeared, as has so happily, confidently, and frequently been predicted. I give in evidence the talents and allegiances of the writers collected here and the richness of their Southern subject matter. It is true that in recent years not only Country Club Republicans from north of the Potomac have moved in, so have hundreds of thousands from south of the Rio Grande. Even so, the Southern distinctiveness may remain. While the South is being dragged along in the direction of the new multi-cultural, metro-sexual America, the rest of the country is moving that way so fast that the gap may even be widening.

Another way to say this is that more of the original America lives on in the South than elsewhere. That alone ought to justify Chronicles noncomformist and prolific treatment of the South over many years as something to be known rather than condemned. Of course, one must understand, as Thomas Fleming has repeatedly pointed out in the pages of Chronicles, that the original America referred to is the one that began at Jamestown, not the one that began at Plymouth Rock and has so long and so zealously been promoted as the one and true and only America.

The South won’t go away. Not yet. For one reason, there are those of us who love her still. For another, those old Southern constitutionalists and agrarian critics of “progress” are for many people beyond Mason-Dixon’s starting to look less like disagreeable relics and more like gifted prophets.

Copyright © 2010 Chronicles Press. Reprinted by permission.