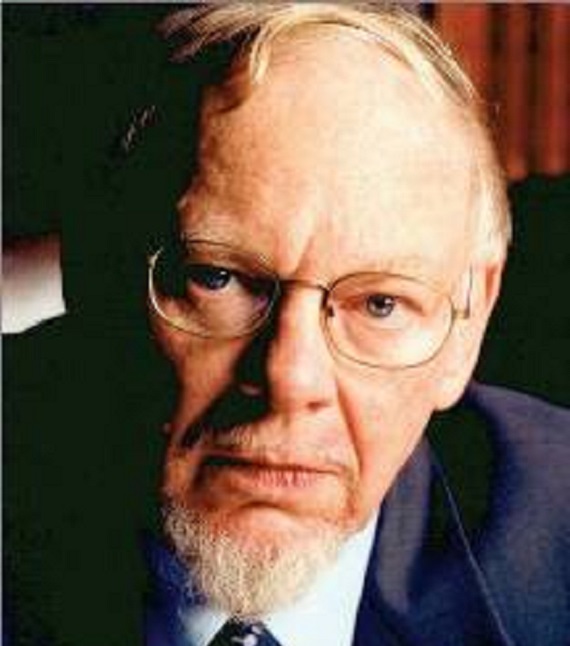

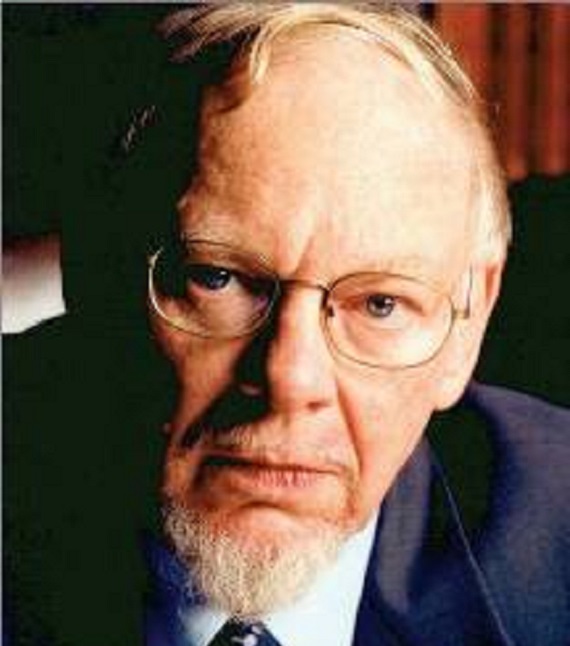

Most people don’t know, but today (June 11) is Clyde Wilson’s birthday.

I had the honor of being Clyde’s last doctoral student. I first met Clyde in the Spring of 1997 as a senior in college trying to decide where to attend graduate school. My top choices were South Carolina and Alabama, Clyde Wilson or Forrest McDonald. My advisor as an undergraduate, Bart Talbert, attended Alabama and had given me a sound education on all things McDonald. He was one of McDonald’s last students.

I left Salisbury, Maryland on my Spring Break determined to find a home for the next several years. I had spoken to Clyde before I left–actually his answering machine–and let him know when I would be arriving in Columbia. South Carolina was my second choice, but I knew of Clyde and his fantastic work on the South and on the Papers of John C. Calhoun. I would be happy there, too, if fate saw fit to send me there.

Clyde’s office was located on the first floor of Gambrell Hall, a grey maze of a building that looked like something Stalin’s architects designed during the Five Year Plans. It should have been a warning. Some of the professors in the history department would have been comfortable goose stepping around Red Square.

I found Clyde’s office, knocked, and in his distinctive way told me to “come in.” He shook my hand, leaned back in his chair, and spoke to me for about thirty seconds before two of his students came sauntering into the room.

“This is Carey Roberts and John Devanny,” Clyde said, “and they will be showing you around.”

That was the last I saw of Clyde. Roberts and Devanny brought me to a little office, turned on the hot lights, and began interrogating me. Why did I want to attend South Carolina? Why did I want to work with Clyde? What did I want to study? And Devanny threw the Oxford dictionary at me. It was akin to reading an Augusta Jane Evans Wilson novel.

I assume I made it through their interview in fine order because Clyde had no objection to working with me. But I still had to meet McDonald at Alabama.

I remember crossing into Alabama with Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama” playing in the background. I still thought Alabama would be my home.

Gary Mills met me at his office in Tuscaloosa, and we went to a local restaurant to chat. Mills was a mountain of a man, as wide as he was tall. I picked a booth and he barely squeezed in. Mills used to go to his office to smoke. His wife didn’t like it. He had a large First National behind his desk and spoke so softly that you had to lean in to hear him. He was an honest historian who wrote about Creoles in Louisiana during and after the War, and he loved the South.

He arranged my meeting with McDonald and McDonald’s wife, Ellen Shapiro McDonald. It was more like a meeting with Mrs. McDonald. Mills introduced me to the McDonalds and they both politely asked me into Forrest’s office. I explained what I wanted to study and how Bart had spoken highly of them. They liked Bart. But Mrs. McDonald very bluntly said, “Go work with Clyde.” Perhaps it was because of what I wanted to do, or maybe it was because they didn’t want to work with me; either way, my course was set. South Carolina it was.

I thought South Carolina and graduate school would be different. Every one of Clyde’s students has a similar story. It was like serving several years in academic purgatory. We were ostracized, criticized, and at times demoralized. The department had it out for Clyde and in turn had it out for us. At least we thought so. There was no conclusive proof, but life in the department was not easy. We were all pariahs, independent thinking students who did not adhere to the “fashionable” trends. Some–the handful of good people in the department both students and faculty–saw that as a benefit; others wanted to marginalize us. Clyde once said that when he arrived at South Carolina he hoped for rigorous academic discussions, real scholarship. He didn’t find it, and all of his students soon realized that no matter what we wrote or researched, it would be ignored by the mainstream historical profession.

I was born in Virginia and have spent almost all of my life in Southern States, but my family is not from the South. My perception of the South had been forged as an undergraduate, and I was drawn to the political and philosophical underpinnings of the Southern tradition. But like many Americans, Southerners included, I considered the “South” to be the four year period between 1861-1865. I had a rather narrow view of Southern history. Clyde changed that.

He once called Jeff Rogers and me to his office to emphasize what we needed to know in order to obtain a Ph.D in history.

He welcomed us in, leaned back in his chair, stroked his beard, crossed his hands on his stomach and said,

“Tell me everything you know about George Washington.”

Jeff and I mumbled a few sputtering words about his political and military career.

“No, what about his family life? His childhood? You need to be able to write a several page paper about Washington with no assistance.”

Silence.

“Ok, tell me everything you know about Thomas Jefferson.”

Again, the same reaction.

“You two have work to do.”

Notice Clyde did not ask us about Robert E. Lee or Jefferson Davis. Certainly, they are important, but he focused on the founding period, and I began to understand then that Southern history encompassed more than the four year fight for independence. My eyes had been opened. The Southern founding, the Jeffersonians, the postbellum South all became more interesting. I could see the South as a culturally distinct region with a four-hundred year history. It was America. That was Clyde’s most important lesson.

Clyde has always wanted to write a book on the civilization of the South, similar to Jacob Burckhardt’s “The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy.” He has an interest in the Southern people, black and white, that most don’t see, particularly those who reduce the defense of the South to a latent desire to re-institute Jim Crow or slavery. That makes their straw man defense easier. Yet, if they bothered to truly read Clyde’s work, they could not come to that conclusion. From John Smith to Walker Percy, Clyde has discussed, researched, written, and expounded upon all elements of Southern history and culture.

I had the benefit of working with Clyde on a regular basis. All of his students did. Most Southerners did not, at least not until the Internet allowed for the free exchange of ideas. The Abbeville Institute allows anyone to become his student, to read, to listen, to understand, to grow, to submerse themselves in the Southern tradition. It would not be the same without Clyde’s decades of work. The South will survive because Clyde has left a trail of bread crumbs for curious, intellectually honest people.

Alabama did eventually become my home. My wife is from Alabama and we live in “the heart of Dixie,” but my education came from Carolina–Tar heel not Palmetto if Clyde has a say in it.

Clyde wrote me the other day apologizing for failing to send a couple of promised articles for the blog. He said that if he lives long enough, he’ll write them next year.

You have too much work to do to die and too many Yankees to annoy by your continued existence. There are thousands of future students, eager minds like mine in 1997, that want to be your student, that want to know Southern culture and history, that want to be proud of their past and their heritage. You cannot let the Yankees win anytime soon.

Happy birthday, Clyde, from every student you have influenced in your life, either directly or indirectly, and many more to come.