The Southern version of Thoreau’s Walden may be considered I’ll Take by Stand, by Twelve Southerners, with its subtitle, The South and the Agrarian Tradition. It was published in 1930 and met with considerable criticism from those who believed it was a futile effort to “turn back the clock” to an idealized utopia of the antebellum South. On the contrary, it was a cautionary tale of the mindless materialism of modern man in the industrial age—the agrarian versus industrial conflict was really a metaphor of the man versus machine conflict. The 12 Southerners ponder the same questions as Thoreau: what are we living for, what is the good life, what are our material and spiritual needs?

While my brother, Clifford, and I attended Vanderbilt University, it hosted “Fifty Years After, A symposium on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of the Agrarian Manifesto. October 30 and 31, November 1, 1980.” Three of the original 12 essayist attended, Lyle Lanier, Andrew Nelson Lytle, and Robert Penn Warren, the poet—perhaps the most famous, along with the poets John Crowe Ransom and Allen Tate who were deceased. I had the program framed. It was still in the air.

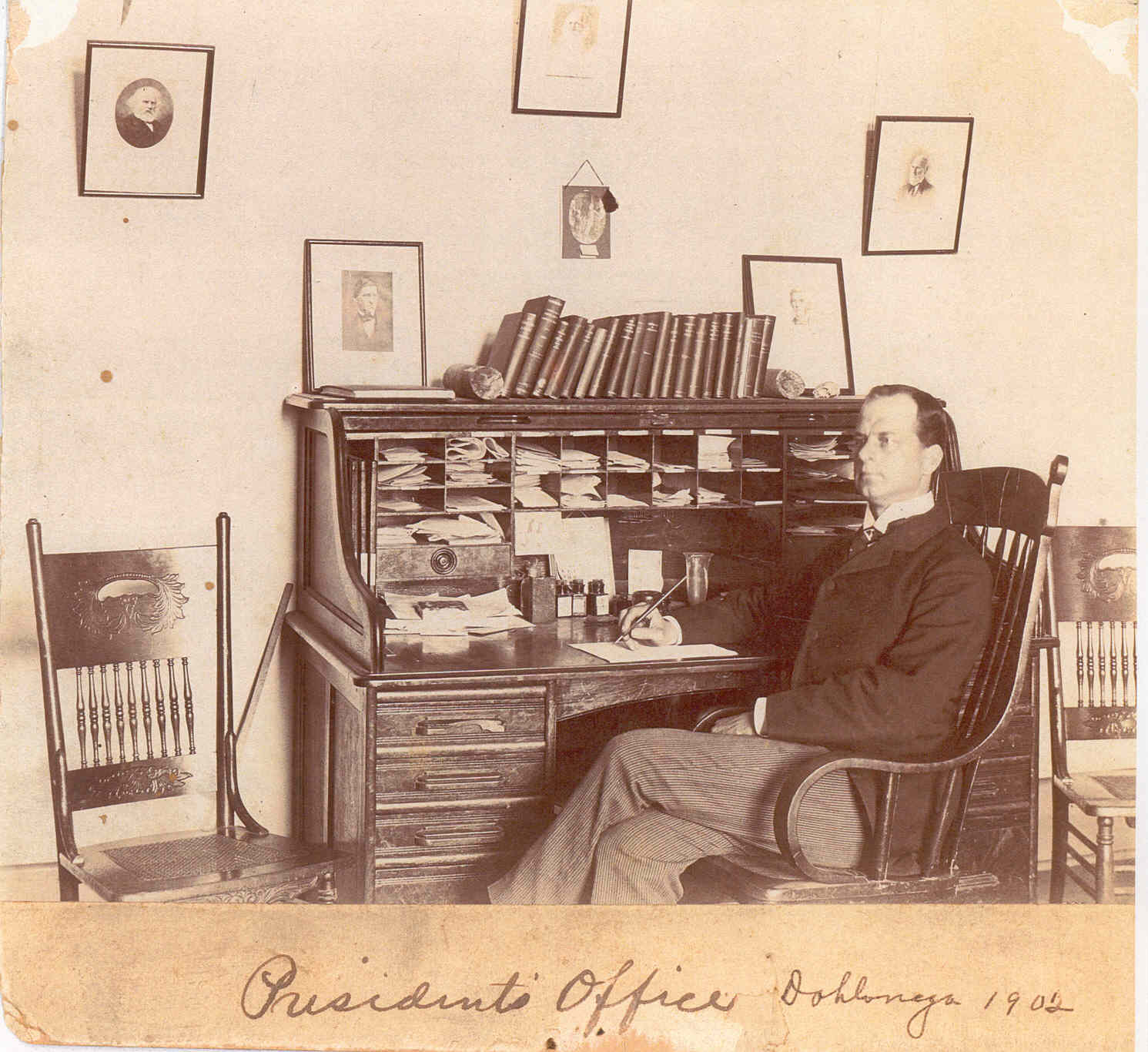

My favorite of the 12 essays is “The Life and Death of Cousin Lucius,” by John Donald Wade, the story of a boy in South Carolina, who moved with his family to Georgia in 1850, was too young to participate in the Civil War (1861-5), but married and raised a family in what Henry Grady called “The New South,” (no longer “The Old South”). This favoritism lies in the observation that the experiences of Lucius, written in 3rd person, are similar to experiences of members of the Roberts and Stewart families of Oxford, Georgia; in reading this story, I am reading about them, my own family. Cousin Lucius reminds me especially of Joseph Spencer Stewart, Jr., who established the high school educational system in Georgia after the Civil War. His tombstone reads, “The State was his Campus.”

Lucius as a child had faint memories of a wagon ride from South Carolina to “a new home in Georgia,” in 1850 where land was “cheap and fresh” (virtually all the Roberts and Stewarts of that generation made the migration from farms in South Carolina to farms in Georgia). The railroad stations eventually determined the town. When the railroad chose to relinquish a station or pass by one town in favor of a different town, the former town “went down almost overnight, almost as suddenly as a blown bladder goes down, pricked” (Before the war, George Washington Roberts moved from Georgia to in Marion, MS, which yielded to Meridian which got the station when the railroad came.).

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, Lucius remembers the Confederate soldiers: “Cousin James and Cousin Edwin went with them—Uncle Daniel’s son and his daughter’s son.” (Numerous Roberts and Stewarts in multiple generations served in the Confederacy, often in the same regiment.) And death followed for many, including George Washington Roberts, the author’s great-great grandfather, buried in the Confederate section of Oakland Cemetery in Atlanta:

What those men had in the wagon was Cousin Edwin’s dead body. Cousin Elvira had not known he was dead. Only that morning she had had a letter from him. He had been killed. How Cousin Elvira wept: He, too wept bitterly, and the wagon men wept also.

Lucius married and had 6 children. With the birth of her 6th child, his wife died, an event which happened to Clifford Rebecca Stewart Roberts, who died giving birth to her 5th child. My grandfather, Stewart Roberts was of a similar age as Lucius:

One day his mother was violently ill. He heard her cry aloud in her agony—as he had before heard her cry, he remembered, two or three distinct times. She was near dying, he judged, for very pain—but the had told him not to come where she was and he waited, himself in anguish for her wretchedness. That day as she bore another child into the world, that lady quit the world once and for all.

Lucius’ family were Methodists, as were the Roberts and Stewarts, many of whom attended Emory College in Oxford, Georgia, a Methodist institution steeped in a rigorous classical education, graduating its first class in 1841. Joseph Spencer Stewart graduated in 1849, the first of 5 generations of his family to graduate from Emory. It was 5 miles from the railroad station in Covington. Two Roberts brothers, Stewart and James, Jr. (and later the author), joined the Southern fraternity, Kappa Alpha Order, like Lucius:

Soon Lucius was sent to a college maintained by Georgia Methodists, and he stayed till he was graduated. The college was in a tiny town remote from the railroad, and it was such a place, that if the generation of Methodists who had set it there some forty years earlier had looked down upon it from Elysium, they would have been happy. Whatever virtues Methodism attained in the South were as manifest there as they were anywhere, and whatever defects it had were less vocal….His teachers were usually Methodist ministers…In his studies the chief characters he met were Virgil and Horace and other Romans, who seemed in that atmosphere, as he understood them, truly native…Lucius knew many other boys like himself. In his fraternity, dedicated to God and ladies he talked much about their high patron and patronesses…They were large-hearted men, in way of being philosophic, and they felt a pity for their own people, in their poverty and in their political banishment form a land that they had governed—no one in his senses would say meanly—through Jefferson, Calhoun, and Lee.

His sisters went to college too: “Sister Cordelia was already at a Methodist college for girls, and Sister Mary would be going soon.” Five Stewart sisters from Oxford went to Wesleyan Female College in Macon. It was customary for the men to attend Emory and the women, Wesleyan.

Like many Emory graduates after the Civil War, Lucius became an educator, starting an academy in the community of his farm. Joseph Spencer Stewart, after graduating from Emory in 1849, did the same and was later Principal of the Preparatory Department (high school) of Emory College. “He was determined to make all these youngsters come to something. After all, his lines were cast as a teacher.” Though “Hard Times shadowed him in night and day,” Lucius married again, this time to his widowed cousin Caroline, who “knew how to summon a group of people from the town and countryside, and how, on nothing, apparently, to provide them with enough food and enough merriment to bring back to all of them the tradition of generous living that seemed native to them” [the Stewart House, run by Miss Emmie and Miss Sallie Stewart, in Oxford, was known for its table].

But the world was changing fast as Lucius turned 50. Industry was displacing agriculture. Friends and family were moving to the city in droves [like Joseph Spencer Stewart who started a hardware store in 1865 in Atlanta, followed there by many of the Roberts and Stewarts]. Perhaps most painful to Lucius was the closure of his academy and its replacement by a public school, following which the tall oaks at the academy were cut down to make way for a basketball court. In his view, “The people had lost faith in the classics as a means to better living, or had come to think of better living in a restricted tangible sense that Cousin Lucius would not contemplate.” The European War (1914-8) passed, he and his wife survived influenza, and he then he died suddenly from a heart attack while walking on his property with his son.

The best characterization of Lucius by John Donald Wade comes early in the essay, however, when Lucius, near the end of college (Emory), visits the state university (The University of Georgia in Athens) as a delegate from his fraternity (Kappa Alpha Order) to a meeting where he meets Alexander Stephens, the former U.S. Senator from Georgia and later Vice-President of the Confederacy. Lucius observes this legendary personality, and also admires the many student imitators, who spoke so eloquently, “when he was sure that he could not speak of anything in final earnest without tending to stutter a little.” Lucius begins to understand more about himself in the world, realizing that “His virtues were of the sort that can be recognized at their entire value only after one has endured the trampling of years which reduce a man to a patriarch.”

Stories of individuals are sometimes more powerful than abstract philosophical essays. Cousin Lucius was based in reality, I may say. It is a beautiful if not tragic tale of an individual possessing the classical virtues forced to adapt to a machine-like transition in society. Of the dozen essays in I’ll Take My Stand,” Cousin Lucius” is the one I go back to.