In the summer of 1863 Confederate soldiers began arriving at Point Lookout Prison, located at the southernmost tip of the Western Shore of Maryland. Too many of these men were to perish there, the captives not of a nation in desperate economic straits, cut off from the rest of the world, but of a wealthy one with access to open ports. Point Lookout was a bitter reminder to the citizens of St. Mary’s County that they were under “the despot’s heel,” a conquered people. With the Yankees in their midst, their young men having crossed the river to fight for the Confederacy, the women and children and the older men who were left behind did what they could to help the POWs and to support the Southern cause.

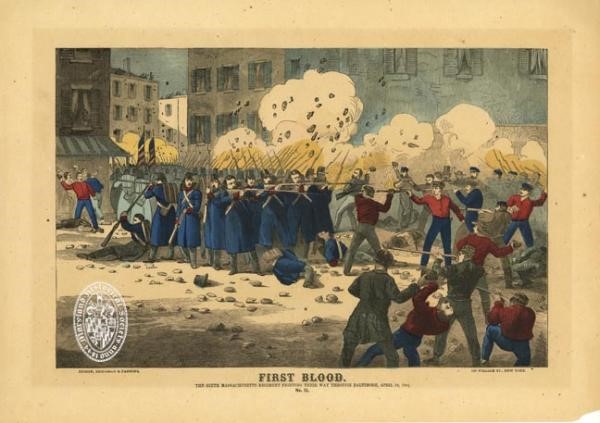

St. Mary’s Countians were not copperheads. They didn’t have “Southern sympathies.” They were Southerners who had secessionist sympathies. In February of 1861, at a gathering in their county honoring George Washington’s birthday, a toast was made to “the Union of the South for the sake of the South.” But as much as the citizens of St. Mary’s loved the whole Southern nation, their greatest affection was reserved for Virginia. Thomas W. Gough, at that same event, toasted the sister states: “Virginia and Maryland having grown together in prosperity, they should cling together in adversity. Like the Siamese Twins, to divide them would be to kill both.”[i] In the wake of the events of April 12, 1861, St. Mary’s Countians pledged to aid the seceded states, to take a stand for Southern independence, resolving to raise $10,000 to purchase arms and ammunition for the defense of Maryland.[ii] Lincoln’s men, however, were mobilized swiftly and in an instant St. Mary’s, like the rest of the Old Line State, was under Union control.

During this time Federal raiders rode through the countryside carrying off slaves to put them to work on contraband farms or to train them to fight for the North. And Northern patrols routinely searched homes for Confederate mail and convalescing wounded soldiers. Often family members were imprisoned at Point Lookout simply because of the Southern service of their loved ones. Dr. James Waring, who lived near the port of Chaptico, was sent to Point Lookout because his two sons, James Jr. and Edward, had joined the Virginia forces.[iii] As soon as the occupation authorities learned of their enlistment, Union soldiers commenced harassing the Warings— Nanny, the six-year-old sister of James and Edward, referred to the unwelcome late-night callers as “those damn-Yankees.”[iv]

The Waring Brothers fought at Gettysburg. Members of Company B of the Maryland Cavalry Unit, “a brave little band of heroes” according to General Grumble Jones, they were captured on July 4, 1863 and found themselves by September of that year at Point Lookout. But they soon slipped away from their captors. Crawling under a pile of bodies on one of the dead wagons, they jumped off of it once it was on the outside. They were to fight in several more battles. Edward was killed in action near Winchester on September 19, 1864.[v]

In the days before the war a resort where wealthy Marylanders and Virginians could stay in rustic cottages, Point Lookout might have had an advantage over some other prisons: In warmer weather, the POWs could fish and crab and also bathe in the Chesapeake, the latter a blessing to men afflicted by infestations of vermin. But the bay also offered a means of escape from the unspeakably cruel conditions of the prison.

POW Luther B. Lake and four other men risked their lives running across the deadline when the guards weren’t looking and silently moved towards the Chesapeake. They then waded along a shoal for five hours, only going two and a half miles. Finally on shore, they crossed a large stream and “[making their] way through jungles and forest,” they came to “an old Colonial residence.” Wary at first, on learning who they were, the owner of the house brought them “a quart bottle of pure old rye whisky” to warm them as they were chilled from wading in the water. Then they all toasted President Davis, General Lee, Stonewall Jackson, J.E.B. Stuart and George Pickett. Years after the war, Lake would declare that the liquor offered the escapees that evening was the “best whisky [he] ever drank in all [his] life.” And in his account of that night, posthumously published in the Confederate Veteran, he writes “When it became day, we were fifteen miles from prison….I have thought about that old Southern gentleman a thousand times since.”[vi]

As they “marched through the peninsula of Maryland,” the soldiers met up with others who aided them in their flight. One man was suspicious of them at first because the POWs were wearing the blue britches of the Yankees,[vii] but they explained that they were using them “to scout in.” When Lake finally convinced him that he and his companions were bona fide Confederates, the old man gave them five dollars and told them to go up the hill to his house where his wife prepared them a “splendid” breakfast.[viii]

The most warm-hearted welcome was yet to come at the house of a Mr. Dent who told them when they asked about his loyalties that he was a “true blue” Southern man but apologized that Grant had married a “near relation” of his. When they realised that they were fugitives from Point Lookout, the Dents prepared for them a “feast,” and, after supper, dressed in her “finest,” Mrs. Dent played the piano for them, the first song she played being “Dixie.” Invited to lodge there in the house for the night, they slept in feather beds “never dreaming of a Yankee.”[ix]

The following day, on learning that they were, in Lake’s words, “Rebel soldiers from Point Lookout prison,” another St. Mary’s County man, a Mr. Bryan, shook their hands and provided them with a boat to cross over the Potomac and victuals to eat along the way. Avoiding Yankee troops on the other side, they finally made their way to their homes in Virginia.[x]

Fifteen year-old Private Solomon Justice, 3rd North Carolina Junior Reserves, however, would not see his home again. Captured in December of 1864 near Fort Fisher and sent to Point Lookout, he passed away there on March 10, 1865, a month before Lee surrendered to Grant.[xi] The number who died at Point Lookout is not certain. Only 3384[xii] names appear on the monument erected by the Federal government, but members of the Descendants of Point Lookout Prisoners of War Organization believe that as many as 14,000 were buried there. For over three decades they have worked to bring attention to both the high death rate at the prison and its causes: apathy, deliberate neglect and retribution on the part of Lincoln and Edwin Stanton. In 1998 the Veterans Administration banned the flying of the Battle Flag year-round at the Federal memorial and demanded the pre-approval by the VA of speeches to be delivered there, justifying this violation of the First Amendment with the customary doublespeak. In response, the descendants purchased land adjacent to the Federal cemetery to establish Confederate Memorial Park, where the Southern colours now fly every day. The dedicated co-chairmen of CMP, Inc., Jim and Christina Dunbar, are adding many new exhibits as their research uncovers ever more facts about an infamous Union prison in a lonesome corner of the occupied South.[xiii]

*************************************************************************************************

[i] St. Mary’s Beacon, March 7, 1861

[ii] Ibid., April 25, 1861 and May 2, 1861

[iii], Betty Waring, The Waring Saga (Leonardtown, MD: Printing Press, Inc., 2014), 33.

[iv] Ibid., 23.

[v] Ibid., 29, 31, 37, 63.

[vi] “Escape from Point Lookout Prison,” Confederate Veteran, June 1929, 219.

[vii] Sometimes a POW whose clothing was in tatters was issued the trousers of the Union soldier to wear.

[viii] Ibid., 219-220.

[ix] Ibid., 220.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Richard H. Triebe, Point Lookout Prison Camp and Hospital (Richard H. Triebe, Revision 2016), 86.

[xii] Four additional deceased POWs are listed as Unknown.

[xiii] Descendants of Point Lookout Prisoners of War and Friends of Confederate Memorial Park, Inc., www.plpow.org.

25,000 Confederate soldiers died in federal prisons. A nearly identical number of yankees died in Confederate prisons. The north was not under naval blockade…the north did not have its agricultural lands put to the torch. Confederate soldiers were deliberately killed in yankee prisons.

bill clinton fat 3 needs to cite his sources…

Mr. Platt, good points.

Wonderful job on the article! I often remind people that Maryland was the first casualty.

I hit the enter button to quickly. I love to hear a good story when there is rye or bourbon whiskey involved.

Thank you!

A fine piece of literature if there ever was one.

Bravo!

Thanks so much!

Nice piece.

Thank you!

The disgraceful and intentional abuse of Confederate POWs is always ignored or papered over, while the rigged war crimes trial of Henry Wirz is trumpeted as evidence of Southern cruelty, despite numerous testimonials from Union POWs that the Johnny Rebs did all in their power for their prisoners. I thank God that He is a God of truth, a God who remembers, a God who will one day make all truth known.

And the refusal of Stanton and Lincoln to honour the terms of the Cartel of Exchange resulted in the deaths of many POWs on both sides. The Confederates at one point were willing to release prisoners unilaterally. But the Yankees were slow in responding to this humanitarian gesture.

Thank you very much for this Article on Point Lookout, where my great-great-great grandfather was a POW. He was blessed to survive and at the end of The War, was made to walk home to South Carolina.

My three-greats grandfather was wounded three times in battle, returned home three times and subsequently returned to fight three times, after each wounding. I am immensely proud of him.

You have every reason to be proud of this Southern hero Vivian.