“Now […] at the height of modern progress, we behold unprecedented outbreaks of hatred and violence; we have seen whole nations desolated by war and turned into penal camps by their conquerors; we find half of mankind looking upon the other half as criminal. Everywhere occur symptoms of mass psychosis. Most portentous of all, there appear diverging bases of value, so that our single planetary globe is mocked by worlds of different understanding. These signs of disintegration arouse fear, and fear leads to desperate unilateral efforts toward survival, which only forward the process.”

— Richard M. Weaver, ‘Ideas Have Consequences’

Recently while passing through a remote Southern village, I found myself wondering why every street corner was adorned with a small American flag. Confused, I tried to recall which national holiday would land on the third week in September. It was only after reaching the outskirts of town though that I realized the display was in honor of the 21st anniversary of 9/11 — Patriot’s Day.

I doubt that I was the only American to be caught unawares. Each September 11th approaches more quietly than the last, and every year we are left wondering whether our wounds have finally healed or we have just learned to ignore them. To recall that tragedy is to conjure a world that feels entirely alien now. The flag-waving of yesteryear elicits embarrassment, and the righteous anger that surged in the early days of the Global War on Terror has all but evaporated. Twenty years, trillions of dollars, and the best blood of a generation yielded none of the fruits promised by that alien world. Instead, the dangers lurking beyond our borders remain, and enemies both seen and unseen continue to plot our destruction. If our intentions were ever noble, surely they were borne out of a desire to protect the near and dear. But soon defending ourselves became a project to transform the world, and along the way we became disfigured ourselves. Now, we struggle to articulate what it was that we were defending in the first place. Was it freedom? Democracy? The homeland?

I found myself in a similar quandary as a young soldier laboring on the edges of the American imperium. My reasons for enlisting in the Army during the Global War on Terror were many. I longed for adventure, and I wanted to prove myself as a man. I also come from a long military tradition reaching back to the early 17th century, and the sacrifices of my forebearers, no matter how distant, have always inspired thoughts and actions. But above all, I believed my nation had been attacked, and I felt a responsibility to defend my family, friends, neighbors and homeland from enemies. However misguided my perception of the world was at the time, that sense of obligation to the near and dear was paramount. Looking back, it was always the essence of my patriotism.

In troubled times like these it should come as no surprise that there is little appetite for patriotism. Exiled to the realm of ideas, where custom, culture, history, and tradition are dissected and dissolved, America is increasingly hard to love. We no longer know how to define our homeland, much less our relation to it. And in an atmosphere like this, can we really fault ourselves for losing faith when America repeatedly fails to embody its Apollonian image or represents the worst impulses of empire? When patriotism is a bumper sticker, a slogan, a shakedown, or merely an assent to nebulous ideals, should we mourn its loss? Is there still a place for it?

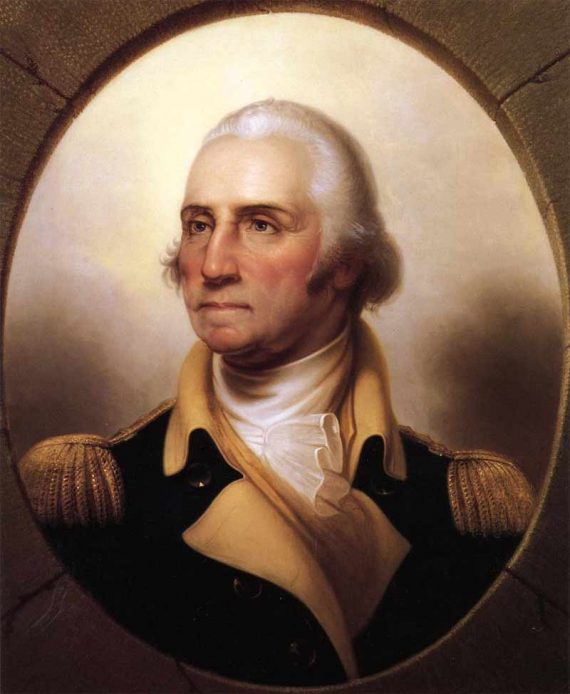

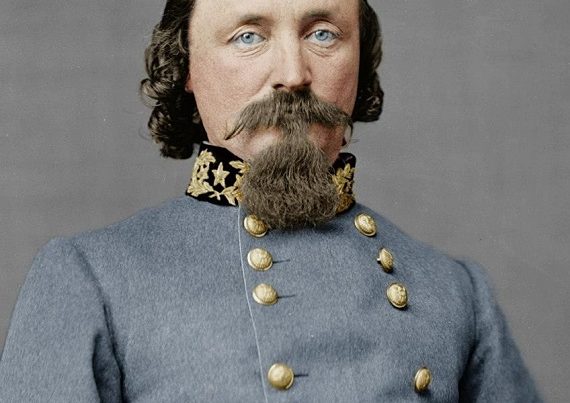

Born under a blue sky in November on a lonely Pennsylvania green, America the idea owes its existence to the genius of an Illinois railsplitter. Just months after the greatest bloodletting in American history, Abraham Lincoln delivered a 272-word address at the dedication of a newly established National Cemetery at Gettysburg. Unlike popular speeches of the period, these remarks at Gettysburg were short and bereft of historical analogy. But Lincoln’s words were poetic and brimming with powerful religious overtones. Through this gnostic injunction, the Railsplitter was able to galvanize his cause, quietly bury the Old Republic of Washington, Adams, and Jefferson, and inaugurate the ‘new birth’ of a nation. Much of our modern understanding of patriotism, national identity, and our country’s origins can be traced to this mythic juncture.

Lincoln’s selective reading of the Declaration of Independence is a cornerstone of our political religion today, and his portrayal of the most devastating war in American history as a purification ritual is widely accepted in North and South alike. Abraham Lincoln’s radical departure from the historical and legalistic confines of the nation’s first founding is his most lasting achievement. Whereas the Declaration of Independence is bound to a certain place and time in history, with a specific people striving to recover their political inheritance as Englishmen, the Gettysburg Address recognizes no such boundaries. Instead, the nation Lincoln speaks into being is one that defers to the primacy of truths far beyond the limitations of law, history and human nature. Uprooted from its ancient constraints, the American nation ceases to be a polity and is rendered an aspirational project – forever condemned to a process of becoming. This is the America of the second founding, America as an idea. And though the disinterested patriot might not fully recognize his conversion and the gulf that separates him from his so-called Founding Fathers, he will inevitably articulate his own patriotism as the pursuit of amorphous ideals, with freedom and equality foremost among them.

One Comment