I. Introduction

The debate over secession and states’ rights has been a contentious issue in American history, dating back to the colonial period. From the earliest days of the Republic, some states argued that they had the right to nullify federal laws they deemed unconstitutional and even to secede from the Union if the federal government became too oppressive. This debate reached its climax in the lead-up to the Civil War, when the issue of states’ rights became the primary cause of the conflict resulting in the secession of eleven southern states.

This paper explores how many states viewed secession and states’ rights from the colonial period to the outbreak of the Civil War. This paper will examine the arguments made by leading political figures in support of states’ rights and secession, as well as the constitutional and legal precedents that informed these debates to achieve this aim. By examining these issues in depth, this paper hopes to shed new light on the ongoing debate over the federal government’s role in relation to the states and provide a more nuanced understanding of the complex political and social forces that shaped the early years of the Republic.

This paper argues that many leading political figures from the American Revolution through the Antebellum period believed the states were sovereign and independent political entities in all spheres constitutionally reserved for them. They also thought the states had a legitimate right to secede from the Union and that any attempt by the federal government to prevent secession was unconstitutional. Drawing on historical, constitutional, and legal sources, as well as economic and social factors, this paper demonstrates that the debate over states’ rights and secession was a critical factor in the lead-up to the Civil War and that it continues to have relevance for contemporary political issues, including the balance of power between the federal government and the states.

II. The American Revolution and the Articles of Confederation

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the original plan of government proposed by the Constitution and how the states understood their role in this government, we need to begin with the American Revolution. During the American Revolution, many colonists believed each colony was fighting for its own independence. The Declaration of Independence states, “These United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be, Free and Independent States.” While the Declaration uses the phrase “United Colonies,” it emphasizes the term “independent states” multiple times in its conclusion. The use of the singular “independent states” denotes that the writers of the Declaration understood that each state was both sovereign and independent. In his Blackstone’s Commentaries: with Notes of Reference, Judge St. George Tucker wrote, “From the moment of the revolution they became severally independent and sovereign states, possessing all the rights, jurisdictions, and authority, that other sovereign states, however, constituted, or by whatever title denominated, possess; and bound by no ties but of their own creation, such except as all other civilized nations are equally bound by, and which together constitute the customary law of nations.”[1]

The American War for Independence concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which recognized each colony as a sovereign and independent state on the international stage. The treaty declared, “His Brittanic Majesty acknowledges the said United States, viz., New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia, to be free sovereign and Independent States; that he treats with them as such, and for himself his Heirs & Successors, relinquishes all claims to the Government, Propriety, and Territorial Rights of the same and every Part thereof.”[2]

The independence and sovereignty of each state were later confirmed under the Articles of Confederation, which referred to itself as a “firm league of friendship” and only granted the national government limited powers related to areas of common interest, such as the common defense of the states, the security of the state’s liberties, and their mutual and general welfare. Section II of the Articles of Confederation declared, “Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled.”[3] Justice Joseph Story noted in his Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States that under the Articles of Confederation, the states, in their sovereign capacity, maintained the bulk of power and control. According to Justice Story, the lack of authority granted to the national government meant it only possessed “but a delusive and shadowy sovereignty, with little more than the empty pageantry of office”[4] and “In short, all powers, which did not execute themselves, were at the mercy of the states.”[5]

III. The Constitutional Convention and the Constitution

The Constitutional Convention aimed to amend the Articles of Confederation to provide for a stronger federal government capable of stabilizing the economy and providing for the common defense. The delegates acknowledged the need to make certain concessions to strengthen the federal government. Still, many of the assembled delegates believed they represented the citizens of each sovereign state rather than the United States as a whole. They remained steadfast in their commitment to preserving the sovereignty of their individual states. The new government established by the Constitution ended the “perpetual union” joined together under the Articles of Confederation. It established a new union with a federal government strong enough to handle issues impacting the states as a whole while preserving and protecting the state’s sovereignty and independence in their domestic affairs.

James Madison explained the framework for the new government during the Virginia Convention when he said, “The powers of the General Government relate to external objects and are but few. But the powers in the States relate to those great objects which immediately concern the prosperity of the people. Let us observe, also, that the powers in the General Government are those which will be exercised mostly in times of war while those of the State governments will be exercised in times of peace.”[6] Madison’s understanding of the constitution was that the federal government would only operate in areas relevant to all of the states focusing its role mainly on external objects. In contrast, the states retained their sovereignty over their domestic issues.

In 1831, John C. Calhoun explained why the states needed to retain their sovereignty over their domestic affairs. He said, “So numerous and diversified are the interest of our country, that they could not be fairly represented in a single government, organized so as to give each great and leading interests, a separate and distinct voice…One General Government was formed for the whole, to which were delegated all the powers supposed to be necessary to regulate the interest common to all the States, leaving others subject to the separate control of the States, being, from their local and peculiar character, such, that they could not be subject to the will of the majority of the whole Union.”[7] Calhoun believed that each state’s distinct culture and interests meant that their people’s needs could not be met or accommodated by a single national government ruling over a united American people. The States and local governments would be more responsive and understanding of the people’s wants and needs. Because of this, Calhoun believed they were more capable of providing for them and protecting their liberties.

Madison and later Calhoun both believed that this new government provided that the states retained all aspects of their sovereignty that they did not expressly delegate to the federal government through the constitution. These delegated powers were limited only to those areas that were of common concern to all the states while preserving for the states the power to control their domestic issues. Judge St. George Tucker explained the concept behind this union of independent states and the retention of their sovereignty when he wrote, “A number of independent states may unite themselves by one common bond or confederacy, for the purpose of common defense and safety, and for the more perfect preservation of amity between themselves, without any of them ceasing to be a perfect, independent, and sovereign state, retaining every power, jurisdiction and right, which it has not expressly agreed shall be exercised in common by the confederacy of the states; and not be any individual state of the Confederacy.”[8] Judge Tucker believed that under the new constitution, the federal government would be “the organ through which the united republics communicate with foreign nations and with each other. Their submission to its operation is voluntary: its councils, its engagements, and its authority are theirs, modified, and united. Its sovereignty is an emanation from theirs, not a flame by which they have been consumed, or a vortex in which they are swallowed up. Each is still a perfect state, still sovereign, still independent.”[9]

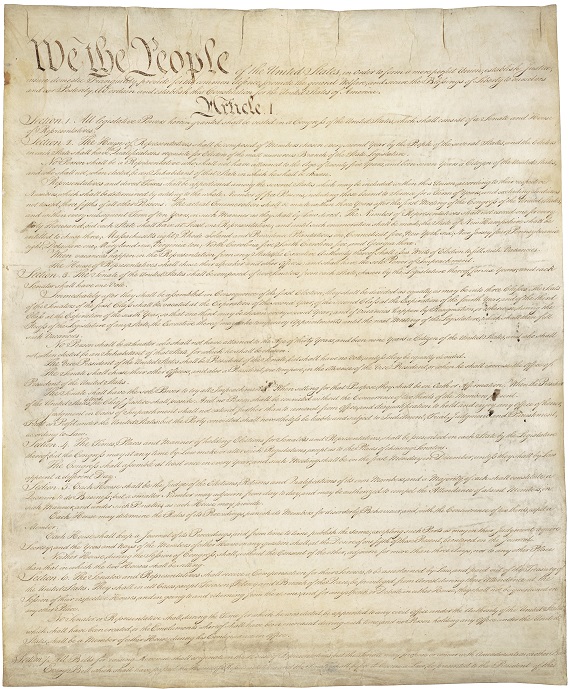

IV. The Preamble

The Constitution begins with the preamble, “We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union….” The term “We the people of the United States” has led many to claim that the Framers intended the population of the United States to be one people in the aggregate. In his Commentary on the Constitution, Justice Story wrote, “We “the people of the United States, do ordain and establish this constitution” is the language; and not we, the people of each state, do establish this compact between ourselves, and the people of the other states. We are obliged to depart from the words of the instrument to sustain the other interpretation; an interpretation which can serve no better purpose, than to confuse the mind in relation to the subject otherwise.”[10]

However, many of the Framers of the Constitution understood the term “the people” to refer to the people of each sovereign state. As far as they were concerned, a united American people did not exist, and they believed the idea of a united people was never expressed in the Constitution. This understanding was supported by Article 7 of the constitution, which states, “The Ratification of the Conventions of nine States shall be sufficient for the Establishment of this Constitution between the States so ratifying the Same.” This provision stipulated that once nine states ratified the constitution, it would only be effective between them. Any state that did not ratify the Constitution would continue to exist outside the United States as a sovereign independent nation. Based on article 7, many states reasonably believed that if the Framers had intended to create one united people, then only a few states with the majority of the population would have been required to ratify it to make it effective and binding upon all thirteen states.

James Madison spoke of this during the Virginia Convention when he pointed out that if no more than a majority of the whole people were necessary for ratification, a convention in Virginia would have been unnecessary, for by the time the Virginia Convention had met, a majority of the people of the United States had already voted to ratify.[11] He also made this point in Federalist No. 39, writing, “That it will be a federal, and not a national act, as these terms are understood by the objectors, the act of the people, as forming so many independent States, not as forming one aggregate nation is obvious from this single consideration, that it is to result neither from the decision of the majority of the people of the union nor from that of a majority of States. It must result from the unanimous assent of the several States that are parties to it…Each State, in ratifying the Constitution, is considered as a sovereign body, independent of all others, and only bound by its own voluntary act.”[12]

During the Virginia Convention, James Madison explained what was meant by “the people.” He said, “Who are parties to it? The people, but not the people as composing one great body, but the peoples as composing thirteen sovereignties.”[13] Neither the Framers of the Constitution nor the state ratification conventions who approved it seemed to have believed “the people” referred to one united group. Alexander Stephens, the U.S. Congressman from Georgia who would go on to become the Vice President of the Confederacy, explained this concept when he wrote, “This is not a government of the people of this country as one nation. It is still, under the Constitution, as it was under the Articles of Confederation, a government of States…It was so submitted to the States for their approval and ratification, and not to the people of the whole country, in the aggregate…Each State retained the absolute power to govern its own people in its own way, in all their domestic relations, without any interference by the people of the other States, or the federal government, except in specified cases set forth in the Constitution.”[14] John C. Calhoun would reiterate this point in his Fort Hill Address in 1831. He said, “The great and leading principle is, that the General Government emanated from the people of the several states, forming distinct political communities, and acting in their separate and sovereign capacity, and not from all the people forming one aggregate political community.”[15]

Moreover, many contended that it would not have made sense for the Framers to have written, “We the people of the United States…” and then listed each state individually as they did not know which states would agree to ratify the Constitution. The Framers even expected that a few states might reject ratification and remain outside the compact forever. In fact, two states, Rhode Island and North Carolina, did not ratify the constitution until much later. Before their ratification, they remained sovereign independent states outside of the Constitutional pact. In a speech given to the United States Senate in 1860, Judah P. Benjamin noted that Rhode Island and North Carolina were treated as sovereign independent states and not part of the Union. He said, “North Carolina and Rhode Island were still foreign nations, and so treated by you, so treated by your laws.”[16] Jefferson Davis, the senator from Mississippi who would go on to become the President of the Confederacy, explained that this was the reason why the individual States were left out of the preamble, “It was found that unanimous ratification of all the states could not be expected, and it was determined, as we have already seen, that the consent of nine states should suffice for the establishment of the new compact between the states so ratifying the same…it became manifestly impracticable to designate beforehand the consenting states by name.”[17]

Additionally, the Constitution referred to the States in the plural showing the writers believed that these were united States, each retaining their individual sovereignty and not coalescing into a single people. In Article 3 Section 2, the jurisdiction of the courts of the general government includes cases arising under “the Laws of the United States and treaties made…under their authority.” Article 3, section 3, defines treason as “levying wars against them…” and Article 1, section 9, declares that “No title of nobility shall be granted by the United States: And no person holding any office of profit or trust under them…”

V. Ratification

In their sovereign capacity, each state called a ratification convention with delegates chosen by the state’s people to decide whether to ascend to the new Constitution. Many states approved ratification ordinances that expressly declared that the state would retain its sovereignty and all powers not explicitly delegated by them to the federal government. South Carolina’s ordinance of ratification stated that “no section or paragraph of the said Constitution warrants a construction that the States do not retain every power not expressly relinquished by them and vested in the general government of the Union.”[18] New York’s ordinance of ratification stated, “That the powers of government may be reassumed by the people, whensoever it shall become necessary to their happiness; that every power, jurisdiction, and right which is not, by the said Constitution, clearly delegated to the Congress of the United States, or the departments of the Government thereof, remains to the people of the several States, or to their respective State governments.”[19] Trying to calm the fears of people who believed the Constitution would deprive the States of their sovereignty, James Madison addressed this issue in the Federalist Papers. He wrote, “I ask, what are these principles? Do they require that, in the establishment of the Constitution, the States should be regarded as distinct and independent sovereigns? They are so regarded by the Constitution proposed.”[20]

VI. The Tenth Amendment

Many States believed it was necessary to further secure state sovereignty and demanded the addition of what would become the tenth amendment to the Constitution. This amendment was created to guarantee that the federal government could never usurp any powers not delegated to it by the sovereign States. The tenth amendment reads, “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.” We have already discussed the language in the ratification ordinances of New York and South Carolina. Other states also took a firm stand on ensuring state sovereignty, and their proposals would eventually be drafted into the tenth amendment. North Carolina proposed that “each state in the union shall respectively retain every power, jurisdiction, and right which is not by this Constitution delegated to the Congress of the United States or to the departments of the General Government.”[21] Rhode Island refused ratification of the Constitution until “Congress shall guarantee to each state its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right which is not by this Constitution expressly delegated to the United States.”[22]

On its face, the Constitution outlined the powers granted to the Federal government and reserved all others for the states. This may have appeared evident to concerned readers at the time of its ratification. It was argued this should have been enough to calm the fears of a federal government usurping powers it was never granted. However, the Tenth Amendment was added by the States to affirm that the general government of the United States only had authority over the powers granted to it in the Constitution. The states wished to retain any powers not explicitly delegated to the Federal government and demanded an amendment that would forever secure aspects of their sovereignty not voluntarily delegated to the federal government.

James Madison stated in the Federalist papers, “In the new government as in the old, the general powers are limited; and that the States, in all unenumerated cases, are left in the enjoyment of their sovereign and independent jurisdiction.”[23] In Federalist No 40, Madison left no doubt about the powers he believed were reserved for the states. He wrote, “The proposed government cannot be deemed a national one; since its jurisdiction extends to certain enumerated objects only, and leave to the several States, a residuary and inviolable sovereignty over all other objects.”[24] And in Federalist No. 45 wrote, “The powers delegated by the proposed constitution to the federal government are few and defined. Those which are to remain in the State governments are numerous and indefinite. The former will be exercised principally on external objects, as war, peace, negotiation, and foreign commerce…The powers reserved to the several States will extend to all objects, which, in the ordinary course of affairs, concern the lives, liberties, and properties of the people”[25] This point was further explained by Judge St. George Tucker in his Blackstone’s Commentaries. Tucker, like Madison and Calhoun, believed that as all domestic affairs were absent as delegated powers in the constitution, they were reserved for the states. He wrote, “Here it ought to be remembered that no case of municipal law can arise under the constitution of the United States, except such as are expressly comprehended in that instrument. For the municipal law of one state or nation has no force or obligation in any other nation; and when several states, or nations unite themselves together by a federal compact, each retains its own municipal laws, without admitting or adopting those of any other member of the union, unless there be an article expressly to that effect.”[26]

VII. Sovereignty not Delegated nor Denied

The Constitution, the tenth amendment, the ratification ordinances of many of the states, and the writings of the framers of the Constitution declared that any power not expressly delegated by the States to the federal government was reserved for the States. We have seen how some states and their leaders believed this was a fundamental principle of the new American government and incorporated language to that effect in their ratification ordinances. They thought that the states ultimately retained all aspects of their sovereignty except for those where they voluntarily surrendered power to the federal government. Alexander Stephens believed the absence of the word “sovereignty” in the constitution when discussing the states supported the position that the states were, in fact, ultimately sovereign. He wrote, “It is true, the word Sovereignty is not in the national constitution, nor had it any business there. But the words State and States abound in it…the word State of itself imports sovereignty as fully as the words Nation, Kingdom, or Empire. When the constitution upon its face showed that it was made by States and for States, it was needless to speak of them as sovereign States; for there cannot be such thing as a State, known and recognized by the public, without sovereignty.”[27]

Stephens and his contemporaries believed the Constitution listed all powers surrendered or delegated by the Sovereign States. Since powers to the federal government were clearly enumerated, it was understood that there could be no passive surrender of any rights held by the States. In Federalist No. 81, Alexander Hamilton explained that a state did not passively surrender any of its sovereign rights. In this essay, Hamilton discusses the possibility of a State being sued in a federal court. He writes, “It is inherent in the nature of sovereignty, not to be amenable to the suit of an individual without its consent. This is the general sense and the general practice of mankind; and the exemption, as one of the attributes of sovereignty, is now enjoyed by the government of every state in the union. Unless therefore, there is a surrender of this immunity in the plan of the convention, it will remain with the states, and the danger intimated must be merely ideal.”[28] President George Washington explained this when on April 28, 1788, he wrote to the Marquis de Lafayette. Washington wrote that the people of the several States “retain everything they do not, by express terms, give up.”[29]

Accordingly, many political leaders of the time believed that any power not mentioned as being surrendered or delegated by the States expressly in the Constitution was a power reserved to the States. This meant that sovereignty, as it was not mentioned in the Constitution, was forever reserved for the individual States. Alexander Stephens explained that “The federal government has no inherent power whatever. It has no power except what is delegated to it by the Sovereign States. All the inherent powers of sovereignty itself not delegated in trust to the general government, nor prohibited to the States, are, it is true, expressly declared in the constitution to be reserved to the States. This shows that as Sovereignty was not parted with, it remained with the States by this express reservation.”[30] Judge St. George Tucker held this same view. He explained that the federal government’s jurisdiction extends only to particular enumerated objects and leaves to the several states a residuary and inviolable sovereignty over all other subjects.[31] He further believed that the powers delegated to the federal government should be strictly construed to be as narrowly defined as possible to prevent it from impacting one of the reserved rights of the states. He explained, “the powers delegated to the federal government, are, in cases, to receive the most strict construction that the instrument will bear, where the rights of a state or of the people may be drawn into question.”[32]

Some argued that the delegation of sovereignty was implied because the states were relinquishing some of their powers to the national government. However, we have seen that many prominent political leaders and the declarations of the states in their ratification ordinances held that no surrender of any power could be implied. According to them, any power given by the states to the federal government must be clear and expressly written in the Constitution. Judge St George Tucker explained this principle when he wrote, “The powers delegated to the federal government being all positive and enumerated, according to the ordinary rules of construction, whatever is not enumerated is retained; for, expressum facit tacere tacitum is a maxim in all cases of construction: it is likewise a maxim of political law, that sovereign states cannot be deprived of any of their rights by implication.”[33]

Moreover, many states believed that delegating some of their sovereign powers in no way denied their full sovereignty. The States were not ordered nor compelled to delegate some of their powers to the national government. Instead, this delegation or restriction of some aspects of their sovereignty was self-imposed by the free consent of the States. The delegation of some of their sovereign powers was done through the constitution, which they held as an agreement between the States to exercise certain specific powers in unison through their designated agent, the federal government. Part of this pact was for the States to refrain from acting separately concerning these delegated powers and to allow the federal government to act on behalf of them all. Accordingly, many believed this voluntary surrender of some of their sovereign powers in no way diminished the sovereignty of the States. Judge St. George Tucker explained that it is a maxim of political law that sovereign states cannot be deprived of their rights by any manner but by their own consent.[34] The States understood this surrender of sovereign powers was voluntary. As we have seen, many States expressly declared in their ratification ordinances that they reserved the right to reassume any of these delegated powers if the federal government should ever abuse these powers. By including such language in their ratification ordinances, States like New York, Rhode Island, and Virginia felt ultimate sovereignty was secured in the hands of the states.

VIII. The Supremacy Clause

It was argued that the Supremacy Clause in Article VI of the Constitution placed ultimate sovereignty and power with the federal government. The Supremacy clause states, “This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.” In his Commentary on the Constitution, Justice Story explained, “If individuals enter into a state of society, the laws of that society must be the supreme regulator of their conduct. If a number of political societies enter into a larger political society, the laws, which the latter may enact, pursuant to the powers entrusted to it by its constitution, must necessarily be supreme over those societies, and the individuals of whom they are composed. It would otherwise be a mere treaty dependent upon the good faith of the parties, and not a government, which is only another name for political power and supremacy.”[35]

It was understood by many of the states that this clause did not undermine their ultimate sovereignty. Instead, they held that this article declared that the supremacy of laws is expressly limited only to laws enacted in line with or “in pursuance thereof” of the federal government’s powers. Alexander Hamilton explained this point in the Federalist Papers when he wrote, “that the laws of the Confederacy, as to the enumerated and legitimate objects of its jurisdiction, will become the supreme law of the land, and that the state functionaries will cooperate in their observance and enforcement with the general government, as far as its just and constitutional authority extends.”[36] He continued in Federalist No 33, writing, “That it expressly confines this supremacy to laws made in pursuant to the constitution.”[37] Judge St. George Tucker discussed this point as well and explained that the federal government is “but a creation of the constitution and having no rights except those that are expressly conferred by the constitution, it can possess no legitimate power except that which is absolutely necessary for the performance of a duty prescribed and enjoined by the constitution.”[38]

Article VI states that the Constitution and the laws and treaties made in accordance with it are supreme, but not that the federal government is supreme. This interpretation was believed to be clear by many of the states when they joined the constitutional compact. They did agree that laws made in accordance with the powers expressly delegated to the Federal government through the Constitution and the Constitution itself are the supreme laws of the land and apply to all of the states, but this was the limit of their supremacy. Alexander Stephens believed that the supremacy clause did not remove supremacy from the States. He wrote, “That two supremes cannot act together is false. They are inconsistent only when they are aimed at each other, or at one indivisible object. The law of the United States are supreme, as to all their proper, constitutional objects; the laws of the States are supreme in the same way. These supreme laws may act on different objects without clashing or they may act on different parts of the same object with perfect harmony.”[39] Stephens understood that anything the Federal government did outside of these delegated powers had no supremacy or authority.

As previously discussed, many states believed they retained ultimate sovereignty and expressed this belief in their ratification ordinances which declared they could reassume any of the powers delegated to the federal government if that agent of the states were to act outside of its designated spheres of authority. In this way, many of these states believed they were the supreme authority and the final arbiters of whether or not the federal government was overstepping its delegated powers. In the Kentucky Resolution in 1798, Thomas Jefferson declared that whenever the Federal government acts outside of its delegated powers, its action is void and of no force, and it was the responsibility of the states as the ultimate sovereigns to check the power of the federal government. It reads, “Whensoever the General Government assumes undelegated powers, its acts are unauthoritative, void, and of no force; that to this compact each State ascended as a State, and is an integral party; that this Government, created by this compact, was not made the exclusive or final judge of the extent of the powers delegated to itself; since that would have made its discretion, and not the Constitution, the measure of its powers, but that, as in all other cases of compact among powers having no common judge, each party has an equal right to judge for itself, as well of infractions as of the mode and measure of redress”[40] James Madison also spoke to this in the Virginia Resolution, writing, “The powers of the federal government, as resulting from the compact, to which the states are parties; as limited by the plain sense and intention of the instrument constituting the compact; as no further valid that they are authorized by the grants enumerated in that compact; and that in case of a deliberate, palpable, and dangerous exercise of other powers, not granted by the said compact, the states who are parties thereto, have the right, and are in duty bound, to interpose for arresting the progress of the evil, and for maintaining within their respective limits, the authorities, rights and liberties appertaining to them.”[41] John C. Calhoun believed that the States were ultimately supreme because it was necessary for them to be the final judge of the Federal government’s actions. He said, “The Constitution of the United States is, in fact, a compact, to which each state is a party…and that the several states, or parties, have a right to judge of its infractions; and in case of a deliberate, palpable, and dangerous exercise of power not delegated, they have the right, in the last resort, to use the language of the Virginia Resolution, to interpose for arresting the progress of the evil and for maintaining, within their respective limits, the authorities, rights, and liberties appertaining to them.”[42] Calhoun believed that the right of a state to interpose itself between the Federal government and its people and its right to nullify an illegal action of the Federal government was “the fundamental principle of our system, resting on facts historically as certain as our revolution itself, and deductions as simple and demonstrative as that of any political, or moral truth whatever.”[43] He so strongly believed in the right of the states to be the final judge of a violation of the constitution that he said, “I firmly believe that on its recognition depend the stability and safety of our political institutions.”[44]

It was understood by Madison, Jefferson, Calhoun, and others that the supremacy clause declared that laws made in accordance with and in pursuance of the powers delegated to the Federal government apply to all of the States and are “supreme,” but this “supremacy” only extended to the powers granted to the federal government by the States through the Constitution.

The states were aware that the Federal government’s powers were enlarged under the Constitution, and its laws were considered supreme in the areas where the power to make those laws was expressly delegated. However, many states still strongly believed the federal government remained subordinate to each sovereign state, which retained the ultimate power to check and limit the Federal government.

IX. Nullification and Interposition

It has been established that many states ascended to the Constitution and believed that, in doing so, they retained all of their sovereign powers unless a specific power was expressly listed in the Constitution as being delegated to the Federal government. Judge St. George Tucker explained that under the constitution, the state governments retained every power, jurisdiction, and right not delegated to the United States by the constitution nor prohibited by it to the states.[45] Furthermore, as previously noted, it was believed by many in the early Republic that the states were the final arbiter of constitutional disputes and, through acts of nullification and in the last resort, secession, the last safeguard for protecting the rights of their citizens against illegal overreach from the federal government.

In his Commentaries on the Constitution, Justice Story explained that this belief developed from the erroneous claim that the constitution was a compact between sovereign states. He wrote, “The cardinal conclusion, for which this doctrine of a compact has been, with so much ingenuity and ability, forced into the language of the constitution (for the language no where alludes to,) is avowedly to establish, that in construing the constitution there is no common umpire; but that each state, nay each department of the government of each state, is the supreme judge for itself, of the powers, rights, and duties, arising under that instrument. Thus, it has been solemnly asserted by some of the state legislatures that there is no common arbiter, or tribunal, authorized to decide in the last resort upon the powers and the interpretation of the constitution”[46]

We have already discussed how Jefferson and Madison, through the Kentucky and Virginia resolutions, stood in open defiance of Justice Story’s position. Both held that it was the state’s right and duty to “interpose for arresting the progress of the evil, and for maintaining within their respective limits, the authorities, rights, and liberties appertaining to them.”[47] And that “this Government, created by this compact, was not made the exclusive or final judge of the extent of the powers delegated to itself; since that would have made its discretion, and not the Constitution, the measure of its powers.”[48]

It was not only the South that rejected Justice Story’s position. Many of the New England states believed they had a right to nullification. New England’s opposition to the embargo act of 1808 raised the issue of the rights of States to stand in defiance of federal actions they believed to be unconstitutional. Representative Samuel Dana of Connecticut said, “If any State believed the Act to be unconstitutional, would it not have been their duty to not comply?”[49] He believed the State legislatures and state officials were sworn to support the Constitution and could refuse assistance, aid, or cooperation if they regarded an act as unconstitutional.[50] Johnathan Trumball, the governor of the State of Connecticut, believed that if Congress were to exceed its constitutional authority, it was the duty of the State legislators to interpose their protecting shield between the rights and liberties of the people and the assumed power of the general government.[51]

The War of 1812 brought the State’s right of nullification and interposition to the forefront in New England. President James Madison was given authorization by congress to call 100,000 militiamen into federal service, but the New England States refused to lend their troops.[52] The Constitution of the United States gives Congress the power to call up a State’s militia in certain situations. It says, “The Congress shall have Power To provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions.” The governor of Massachusetts, Caleb Strong, believed that the governor of the state was the only person in a position to determine whether this call to federal service was necessary. He held that since there was no foreign invasion of New England at the time and since no domestic insurrection existed, he could not comply with the President’s request for his State’s militia to be called into federal service.[53]

In 1814 Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and Vermont met to discuss their response to what they believed to be the federal government’s abuses of power during the War of 1812. Daniel Webster delivered a speech critical of the federal government’s proposed conscription of state militia troops to aid the war effort. He said, “It will be the solemn duty of the State Governments to protect their own authority over their own militia and to interpose between their citizens and arbitrary power. These are among the objects for which the State Governments exist; and their highest obligations bind them to the preservation of their own rights and the liberties of their people.”[54]

In 1850 The United States Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act. This Act would compel many northern states to use the doctrine of nullification and even threaten secession. In this instance, nullification would not only be directed at the federal congress but at decisions of the Supreme Court and its effect on State sovereignty. Enacted on September 18, 1850, the act put fugitive slave cases exclusively under federal jurisdiction. Citizens who attempted to prevent the arrest of suspected fugitive slaves or helped to hide fugitive slaves could be subject to six months in prison, struck with a $1,000 fine, and subjected to additional civil damages of $1,000 for each fugitive who escaped.[55]

In Wisconsin, an abolitionist named Sherman Booth was arrested for violating the Fugitive Slave Act by helping to rescue a runaway slave. A federal marshal arrested him, but since Wisconsin had no federal prisons, the marshal was forced to detain him in a local jail. Booth requested and was granted a writ of habeas corpus from the Wisconsin State Supreme Court on the grounds that the federal act was unconstitutional. The federal marshal appealed the decision of the Wisconsin Supreme Court to the Supreme Court of the United States. To no one’s surprise, the Supreme Court ordered that Booth be re-arrested. Booth was then tried and convicted in federal court, but immediately after sentencing, he was released again by order of the Wisconsin Supreme Court.[56]

The north and abolitionists in the north were so supportive of States’ rights and nullification in opposing the Fugitive Slave Act that Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune wrote, “Republicans naturally stand on the State-Rights doctrine of Jefferson.”[57] Benjamin Wade, a Radical Republican, declared, “I am no advocate for Nullification, but in the nature of things, according to the true interpretation of our institutions, a State, in the last resort, crowded to the wall by the General Government seeking by the strong arm of its power to take away the rights of the State, is to judge of whether she shall stand on her reserved rights.”[58] In 1850 Vermont passed the Habeas Corpus Law, which intended to make the federal fugitive slave act null and void within the state’s boundaries.[59] This law made it nearly impossible to enforce the fugitive slave act in Vermont. Vermont was using the same tactic of nullification that South Carolina had used in 1832 when they attempted to block federal tariffs.[60]

Other northern Republicans expressed their belief that the people, not the federal supreme court, were the Constitution’s final arbiter. Vice President Hannibal Hamlin denied the Supreme Courts ability to “decide a political question for us . . . We make the laws, they interpret them; but it is not for them to tell us . . . what is a political constitutional right.”[61] Lincoln himself spoke of the people’s authority as the ultimate arbiters of the Constitution in his first inaugural address, saying, “[I]f the policy of the government, upon vital questions, affecting the whole people, is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court, the instant they are made . . . the people will have ceased, to be their own rulers, having, to that extent, practically resigned their government, into the hands of that eminent tribunal.”[62] Lincoln’s position was backed up by Alexander Hamilton, who wrote in Federalist No 33, “If the federal government should overpass the just bounds of its authority, and make tyrannical use of its powers; the people whose creature it is, must appeal to the standard they have formed, and take such measures to redress the injury done to the constitution, as the exigency may suggest and prudence justify.”[63]

X. Secession

The right for a State to secede from the Union was not mentioned anywhere in the Constitution, and there was no express delegation of any power to the Federal government to prevent a State from seceding. For this reason, statesmen like Judah P. Benjamin declared in 1860 that “the right of secession results from the nature of the compact itself; that it must necessarily be one of those reserved powers which was not abandoned by it, and therefore grows out of the Constitution, and is not in violation of it.”[64]

It has been established that the prevailing view held by many states leading up to the Civil War was that no power of a state could be passively surrendered, and the surrender of the right of secession was not found in the Constitution. Accordingly, many states and their leaders held that the right of secession was a power retained by the States. Jefferson Davis wrote that far from being against the Constitution or incompatible with it, “we contend that if the right to secede is not prohibited to the states, and no power to prevent it expressly delegated to the United States, it remains as reserved to the states of the people, from whom all the powers of the general government were derived.”[65] Davis believed it was unnecessary for the Constitution to affirm the right of secession because it was an attribute of sovereignty, and the states had reserved all attributes of sovereignty which they had not expressly delegated.[66]

New York, Virginia, and Rhode Island all included the express right to secession in their ordinances of ratification, showing they understood this to be an element of their sovereignty they did not surrender upon joining the Union. Virginia’s ordinance said, “In the name and in behalf of the people of Virginia, declare and make known that the powers granted under the Constitution, being derived from the people of the United States may be resumed by them whensoever the same shall be perverted to their injury or oppression, and that every power not granted thereby remains with them….”[67] New York’s ordinance of ratification said, “That the Powers of Government may be reassumed by the People, whensoever it shall become necessary to their Happiness; that every Power, Jurisdiction and right, which is not by the said Constitution clearly delegated to the Congress of the United States, or the departments of the Government thereof, remains to the People of the several States, or to their respective State Governments to whom they may have granted the same.”[68] Finally, Rhode Island reserved the right of secession in its ratification ordinance, which said, “That the powers of government may be reassumed by the people whensoever it shall become necessary to their happiness.”[69] In ratifying the Constitution, these states understood they reserved the right to reassume any power delegated to the Federal government and to leave the Union if it was in the best interest of their people.

XI. Coercion

If nullification and secession were not rights reserved to the States, then it was believed the federal government must be able to use coercion to compel the States to follow its will; however, a provision for this is found nowhere in the Constitution. Alexander Hamilton vehemently protested including the use of force in the Constitution against a non-compliant state. In the New York convention, he said, “To coerce the States is one of the maddest projects that was ever devised…what picture does this idea present to our view? A complying State at war with a non-complying State: Congress marching the troops of one State into the bosom of another:…Here is a nation at war with itself. Can any reasonable man be well disposed towards a government which makes war and carnage the only means of supporting itself – a government that can only exist by the sword?”[70] Edmund Randolph. The governor of Virginia expressed the same sentiment when, at the Virginia convention, he said, “What species of military coercion could the general government adopt for enforcement of obedience to its demands? Either an army sent into the heart of a delinquent state, or blocking up its ports. Have we lived to this, then, that, in order to suppress and exclude tyranny, it is necessary to render the most affectionate friends the most bitter enemies, set the father against the son, and make the brother slay the brother? Is this the happy expedient that is to preserve liberty? Will it not destroy it?”[71] During the debates in the Federal Convention of 1787, James Madison expressly condemned giving the federal government the authority to exert force against a delinquent State stating, “The use of force against a State would look more like a declaration of war than an infliction of punishment; and would probably be considered by the party attacked as a dissolution of all previous compacts by which it might be bound.”[72]

John C. Calhoun understood the dangers of forcing the States into compliance. In a speech written by him and delivered by Mr. Mason of Virginia to the Senate, he said, “Force might keep them connected, but the combination would partake more of the character of subjugation on the part of the weaker to the stronger than the Union of free, independent, sovereign States in one Confederation, as they stood in the early days of government, and which only is worthy the name of Union.”[73]

Before the outbreak of the Civil War, President Buchanan wrestled with the idea of whether the federal government could coerce a State to remain in the Union by force. His Attorney General, Jeremiah Black, wrote a legal opinion on the matter stating, “Whether Congress has the constitutional right to make war upon one or more States and require the Executive of the Federal Government to carry it on by means of force to be drawn from the other States, is a question for Congress itself to consider… It must be admitted that no such power is expressly given; nor are there any words in the Constitution which imply it. Among the powers enumerated in Article 1, Section 8, [it] certainly means nothing more than the power to commence and carry on hostilities against the foreign enemies of the nation.”[74] Based on this legal opinion and his beliefs, Buchanan felt that the federal government had no legal authority to coerce a state by force or violence. Buchanan believed that the “Union rests upon public opinion, and can never be cemented by the blood of its citizens shed in civil war. If it cannot live in the affections of the people, it must one day perish. Congress may possess many means of preserving it by conciliation, but the sword was not placed in their hand to preserve it by force.”[75]

The ability to use force against a non-conforming State was conspicuously absent from the Constitution. This absence was acknowledged by the leading pro-secessionist and states’ rights leaders before the Civil War. Calhoun, Davis, Stephens, Benjamin, and others believed that the absence of the ability of the federal government to coerce a state by force to stay in the union meant that any attempt for the federal government to do so would be unconstitutional.

XII. Conclusion

In the early republic, many leading figures believed each of the original thirteen States individually gained their independence with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, remained independent and sovereign with the adoption of the Articles of Confederation, and carried that sovereignty into the Constitutional pact where they only surrendered specific powers listed in the Constitution to the federal government. They held that the constitution reserved to the states any powers not expressly delegated to the federal government, including the right to reassume the whole exercise of their sovereignty. John C. Calhoun said, “We must view the General Government and those of the States as a whole, each in its proper sphere, sovereign and independent; each perfectly adapted to its respective objects; the States acting separately, representing and protecting the local interest; and acting jointly through one General Government, with the weight respectively assigned to each by the Constitution.”[76]

Judge St. George Tucker summarized his understanding of the American government when he wrote, “The Constitution of the United States, then, being that instrument by which the Federal Government hath been created, its powers defined and limited, and the duties and functions of its several departments proscribed, the Government, thus established, may be pronounced to be a Confederate Republic, composed of several independent and sovereign democratic States, united for their common defense and security against foreign nations, and for the purposes of harmony and mutual intercourse between each other; each State retaining an entire liberty of exercising, as it thinks proper, all those parts of sovereignty which are not mentioned in the Constitution, or Act of Union, as parts that ought to be exercised in common.”[77] Judge Tucker and many of his contemporaries saw the Constitution of the United States as a federal compact where sovereign and independent states united themselves without each ceasing to be a perfect state.

John C. Calhoun would close his Fort Hill Address by explaining his understanding of the Federal government’s role and its relationship to the states. He said, “The states formed the compact, acting as sovereign and independent communities. The General government is but its creature; and though, in reality, a government, with all the rights and authority which belong to any other government, within the orbit of its powers, it is, nevertheless, a government emanating from a compact between sovereigns, and partaking, in its nature and object, of the character of a joint commission, appointed to superintend and administer the interest in which all are jointly concerned; but having, beyond its proper sphere, no more power than if it did not exist.”[78]

This paper has argued that many of the original and later states joining the union believed in their sovereignty and independence as political entities. Many asserted their legitimate right to nullify a federal law that went beyond the scope of the federal government’s power, even if the law was deemed constitutional. This belief was exemplified by the rejection of the Fugitive Slave Act by many northern states that considered it an infringement of their citizens’ rights and liberties. Furthermore, through their ratification ordinances, many states declared that they could reassume all powers delegated to the federal government and secede from the union as the ultimate expression of their sovereignty. The secession of eleven Southern states in 1861 was therefore seen as an exercise of their sovereign right as independent states. These arguments underscored the firm belief in state sovereignty held in the early years of the republic through the antebellum period, which played a significant role in shaping the political landscape of the United States leading up to the Civil War.

The question of the balance of power between the federal government and the states remains an important one. The arguments made for states’ rights leading up to the Civil War have implications for ongoing debates about federalism, constitutional interpretation, and the nature of American democracy. Supreme Court Justice Salmon P. Chase famously said, “States’ rights died at Appomattox .” While the outcome of the Civil War has largely settled the question of secession, the issues raised by this debate continue to shape American political discourse. We must continue to examine them closely to ensure that the principles of democracy and liberty are preserved for future generations.

**************

[1] Tucker, St. George. “Blackstone’s Commentaries: With Notes of Reference (1803).” LONANG Institute. https://lonang.com/library/reference/tucker-blackstone-notes-reference/tuck-1d1/.

[2] “Treaty of Paris (1783).” National Archives. September 3, 1783. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/treaty-of-paris.

[3] “Articles of Confederation (1777).” National Archives. November 15, 1777. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/articles-of-confederation?_ga=2.222822936.2026622530.1667842630-194205229.1664139975.

[4] Story, Joseph. 2020. Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States. Cosimo Classics.

[5] Story, Joseph. 2020. Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States. Cosimo Classics.

[6] Madison, James. “Power to Levy Direct Taxes, [11 June] 1788.” Founders Online. June 11, 1788. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-11-02-0074.

[7] Calhoun, John C. “Fort Hill Address.” Teaching American History. July 26, 1831. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/fort-hill-address/.

[8] Tucker, St. George. “Blackstone’s Commentaries: With Notes of Reference (1803).” LONANG Institute. https://lonang.com/library/reference/tucker-blackstone-notes-reference/tuck-1d1/.

[9] Tucker, St. George. “Blackstone’s Commentaries: With Notes of Reference (1803).” LONANG Institute. https://lonang.com/library/reference/tucker-blackstone-notes-reference/tuck-1d1/.

[10] Story, Joseph. 2020. Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States. Cosimo Classics.

[11] McDonald, F. (2000). States’ Rights and the Union (p. 22). University Press of Kansas.

[12] Hamilton, Alexander, Madison, James, and John Jay. 2006. The Federalist. Barnes & Noble Books

[13] Straub, Steve. “James Madison, Speech at the Virginia Convention to ratify the Federal Constitution.” The Federalist Papers. July 28, 2013. https://thefederalistpapers.org/founders/madison/james-madison-speech-at-the-virginia-convention-to-ratify-the-federal-constitution.

[14] Stephens, Alexander H. 2015. A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States. The Lawbook Exchange, LTD.

[15] Calhoun, John C. “Fort Hill Address.” Teaching American History. July 26, 1831. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/fort-hill-address/.

[16] Benjamin, Judah P. “Speech of Hon. J. P. Benjamin, of Louisiana, on the Right of Secession. Delivered in the Senate of the United States.” Speech, December 31, 1860.

[17] Davis, Jefferson. 2010. The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. Barnes & Noble, Inc.

[18] “South Carolina’s Ratification.” The U.S. Constitution Online. May 23, 1788. https://usconstitution.net/rat_sc.html.

[19] “New York’s Ratification.” The Historical Society of the New York Courts. September 17, 1788. https://history.nycourts.gov/ratification-statement/.

[20] Hamilton, Alexander, Madison, James, and John Jay. 2006. The Federalist. Barnes & Noble Books.

[21] “North Carolina’s Ratification.” The U.S. Constitution Online. November 21, 1789. https://www.usconstitution.net/rat_nc.html.

[22] “Rhode Island’s Ratification.” The U.S. Constitution Online. May 29, 1790. https://usconstitution.net/rat_ri.html.

[23] Hamilton, Alexander, Madison, James, and John Jay. 2006. The Federalist. Barnes & Noble Books.

[24] Hamilton, Alexander, Madison, James, and John Jay. 2006. The Federalist. Barnes & Noble Books.

[25] Hamilton, Alexander, Madison, James, and John Jay. 2006. The Federalist. Barnes & Noble Books.

[26] Tucker, St. George. “Blackstone’s Commentaries: With Notes of Reference (1803).” LONANG Institute. https://lonang.com/library/reference/tucker-blackstone-notes-reference/tuck-1d1/.

[27] Stephens, Alexander H. 2015. A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States. The Lawbook Exchange, LTD.

[28] Hamilton, Alexander, Madison, James, and John Jay. 2006. The Federalist. Barnes & Noble Books.

[29] “George Washington Letter to the Marquis de Lafayette April 28, 1788.” Revolutionary War and Beyond. April 28, 1788. https://www.revolutionary-war-and-beyond.com/george-washington-letter-to-the-marquis-de-lafayette-april-28-1788.html.

[30] Stephens, Alexander H. 2015. A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States. The Lawbook Exchange, LTD.

[31] Tucker, St. George. “Blackstone’s Commentaries: With Notes of Reference (1803).” LONANG Institute. https://lonang.com/library/reference/tucker-blackstone-notes-reference/tuck-1d1/.

[32] Tucker, St. George. “Blackstone’s Commentaries: With Notes of Reference (1803).” LONANG Institute. https://lonang.com/library/reference/tucker-blackstone-notes-reference/tuck-1d1/.

[33] Tucker, St. George. “Blackstone’s Commentaries: With Notes of Reference (1803).” LONANG Institute. https://lonang.com/library/reference/tucker-blackstone-notes-reference/tuck-1d1/.

[34] Tucker, St. George. “Blackstone’s Commentaries: With Notes of Reference (1803).” LONANG Institute. https://lonang.com/library/reference/tucker-blackstone-notes-reference/tuck-1d1/.

[35] Story, Joseph. 2020. Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States. Cosimo Classics.

[36] Hamilton, Alexander, Madison, James, and John Jay. 2006. The Federalist. Barnes & Noble Books.

[37] Hamilton, Alexander, Madison, James, and John Jay. 2006. The Federalist. Barnes & Noble Books.

[38] Tucker, St. George. “Blackstone’s Commentaries: With Notes of Reference (1803).” LONANG Institute. https://lonang.com/library/reference/tucker-blackstone-notes-reference/tuck-1d1/.

[39] Stephens, Alexander H. 2015. A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States. The Lawbook Exchange, LTD.

[40] Jefferson, Thomas. “III. Resolutions Adopted by the Kentucky General Assembly, 10 November 1798.” Founders Online. November 10, 1798. https://founders.archives.gov/?q=Ancestor%3ATSJN-01-30-02-0370&s=1511311111&r=4

[41] Madison, James. “Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions (1798).” Bill of Rights Institute. December 24, 1798. https://billofrightsinstitute.org/primary-sources/virginia-and-kentucky-resolutions.

[42] Calhoun, John C. “Fort Hill Address.” Teaching American History. July 26, 1831. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/fort-hill-address/.

[43] Calhoun, John C. “Fort Hill Address.” Teaching American History. July 26, 1831. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/fort-hill-address/.

[44] Calhoun, John C. “Fort Hill Address.” Teaching American History. July 26, 1831. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/fort-hill-address/.

[45] Tucker, St. George. “Blackstone’s Commentaries: With Notes of Reference (1803).” LONANG Institute. https://lonang.com/library/reference/tucker-blackstone-notes-reference/tuck-1d1/.

[46] Story, Joseph. 2020. Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States. Cosimo Classics.

[47] Madison, James. “Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions (1798).” Bill of Rights Institute. December 24, 1798. https://billofrightsinstitute.org/primary-sources/virginia-and-kentucky-resolutions.

[48] Jefferson, Thomas. “III. Resolutions Adopted by the Kentucky General Assembly, 10 November 1798.” Founders Online. November 10, 1798. https://founders.archives.gov/?q=Ancestor%3ATSJN-01-30-02-0370&s=1511311111&r=4

[49] McDonald, Forrest. 2000. States’ Rights and the Union. University Press of Kansas.

[50] McDonald, Forrest. 2000. States’ Rights and the Union. University Press of Kansas.

[51] McDonald, Forrest. 2000. States’ Rights and the Union. University Press of Kansas.

[52] McDonald, Forrest. 2000. States’ Rights and the Union. University Press of Kansas.

[53] McDonald, Forrest. 2000. States’ Rights and the Union. University Press of Kansas.

[54] McDonald, Forrest. 2000. States’ Rights and the Union. University Press of Kansas.

[55] McDonald, Forrest. 2000. States’ Rights and the Union. University Press of Kansas.

[56] McDonald, Forrest. 2000. States’ Rights and the Union. University Press of Kansas.

[57] McDonald, Forrest. 2000. States’ Rights and the Union. University Press of Kansas.

[58] McDonald, Forrest. 2000. States’ Rights and the Union. University Press of Kansas.

[59] Bushnell, Mark. “Then Again.” The Vermont Independent. November 13, 2016. https://vermontindependent.net/tag/habeas-corpus-law/

[60] Bushnell, Mark. “Then Again.” The Vermont Independent. November 13, 2016. https://vermontindependent.net/tag/habeas-corpus-law/

[61] “How Abraham Lincoln Fought the Supreme Court.” Jacobin. September 19, 2022. https://jacobin.com/2020/09/abraham-lincoln-supreme-court-slavery.

[62] “Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address.” American Battlefield Trust. Accessed January 19, 2023. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/primary-sources/lincolns-first-inaugural-address.

[63] Hamilton, Alexander, Madison, James, and John Jay. 2006. The Federalist. Barnes & Noble Books.

[64] Benjamin, Judah P. “Speech of Hon. J. P. Benjamin, of Louisiana, on the Right of Secession. Delivered in the Senate of the United States.” Speech, December 31, 1860.

[65] Davis, Jefferson. 2010. The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. Barnes & Noble, Inc.

[66] Davis, Jefferson. 2010. The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. Barnes & Noble, Inc.

[67] “Virginia’s Ratification.” The U.S. Constitution. June 26, 1778. https://www.usconstitution.net/rat_va.html.

[68] “New York’s Ratification.” The Historical Society of the New York Courts. September 17, 1788. https://history.nycourts.gov/ratification-statement/.

[69] “Rhode Island’s Ratification.” The U.S. Constitution Online. May 29, 1790. https://usconstitution.net/rat_ri.html.

[70] Davis, Jefferson. 2010. The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. Barnes & Noble, Inc.

[71] Davis, Jefferson. 2010. The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. Barnes & Noble, Inc.

[72] Madison, James. 1787. DEBATES IN THE FEDERAL CONVENTION OF 1787. The Federalist Papers Project. https://www.thefederalistpapers.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Debates-in-the-Federal-Convention-of-1787.pdf.

[73] Stephens, Alexander H. 2015. A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States. The Lawbook Exchange, LTD.

[74] “Attorney General Black’s Opinion Of The Events Of Nov. 20, 1860.” American Civil War Forum. September 27, 2012. https://www.americancivilwarforum.com/attorney-general-blacks-opinion-of-the-events-of-nov.-20-1860-2083919.html.

[75] Davis, Jefferson. 2010. The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. Barnes & Noble, Inc.

[76] Calhoun, John C. “Fort Hill Address.” Teaching American History. July 26, 1831. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/fort-hill-address/.

[77] Tucker, St. George. “Blackstone’s Commentaries: With Notes of Reference (1803).” LONANG Institute. https://lonang.com/library/reference/tucker-blackstone-notes-reference/tuck-1d1/.

[78] Calhoun, John C. “Fort Hill Address.” Teaching American History. July 26, 1831. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/fort-hill-address/.

I can’t believe I am reading this at Abbeville Institute. Hasn’t this author read Clyde Wilson, Don Livingston, Tom DiLorenzo et al? Hasn’t the author read the ratification documents of NY, RI and VA? To boil things down to their simplest form, everyone in ante-bellum America believed in the right of secession. The ones who did not were lying for personal financial gain via a Hamiltonian/Clay/Lincoln mercantilist system which they wished to impose. End of debate. Apologies for being so blunt and Yankee like. Is this author a transplant, Carpetbagger or a Scalawag? I can’t believe he is this ill-informed and not one of those things.

“…the word State of itself imports sovereignty as fully as the words Nation, Kingdom, or Empire. When the constitution upon its face showed that it was made by States and for States, it was needless to speak of them as sovereign States; for there cannot be such thing as a State, known and recognized by the public, without sovereignty.”

This has always been what confused me about the “preserving the Union” crowd. If States can’t leave the Union, they are no longer States. The word Union tells you exactly what the gov’t. established by the U.S. Constitution is: a federal republic. To deny the sovereignty of the States and preserve the Union by force is to fundamentally alter the nature of both States and Union and erect something else in their place. How it took the violent changes of Reconstruction to demonstrate this truth to Northern Democrats and such intelligent men as R.E. Lee and Richard Taylor, I cannot fathom.

A nicely written essay, but with all due deference, the “outcome” of the “Civil War” has not “largely settled the question of secession.” Indeed, dissolution has never been more desired on the part of the unreconstructed. America is an abomination.

I enjoyed reading this paper with the exception of the last paragraph, which ruined it for me. Most of the information seems on par with what I am learning, but in that last paragraph, there are so many issues, and I am so incredibly tired of the word “democracy” when talking about the USA. The so-called “civil war” showed how little Lincoln was really interested in the sovereignty of the States – it did not settle any debate.