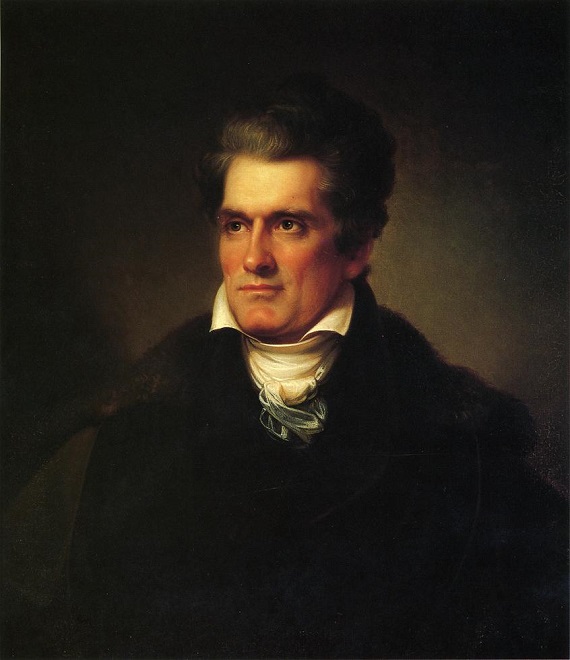

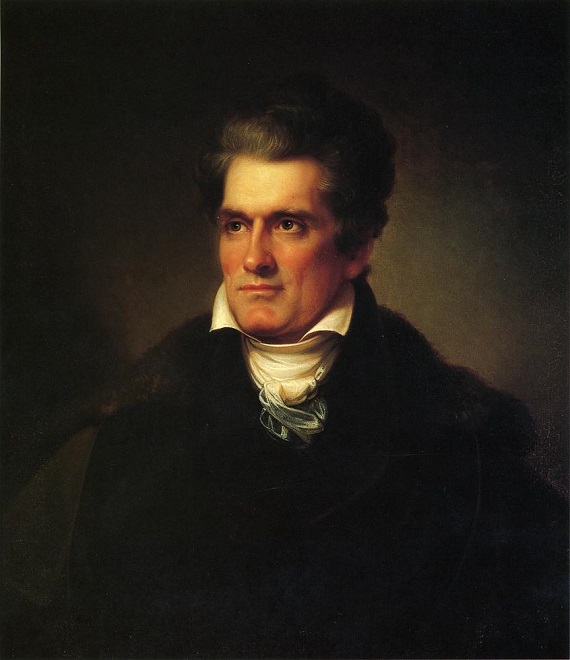

Southern conservatism is considered an enigma when juxtaposed against the bipartisan political configuration having been imposed upon us since the beginning of the American experiment. The candor of its echoed sentiment as a past relic meets the ears of many contemporary Americans with halted sails as its message could never penetrate their intellect. When the essence of its subject is given the slightest credence, however an anomaly it may be, the human condition is realized, and a shred of faith is foisted upon the social order as a revelation has occurred within his egg-shelled mind. This revelation comes not in the form of a plank of a political platform, nor as novel policy initiative (as is the preferred methodology considered by our latest political elite.) Rather southern conservatism reforms its inheritor through a philosophical means that stands exterior to any political class, party, or from any linear or spectral delineations of any given political ideology. Southern conservatism is an understanding of the natural transmission of government and community whereas a symbiotic relationship is erected to progress the human condition, as which are the ends the relationship hopes to effectuate. As John C. Calhoun in his Disquisition on Government stated, “herein is to be found the principle which assigns power and liberty their proper spheres and reconciles each to the other under all circumstances. For, if power be necessary to secure to liberty the fruits of its exertions, liberty, in turn, repays power with interest, by increased population, wealth, and other advantages, which progress, and improvement bestow on the community. By thus assigning to each its appropriate sphere, all conflicts between them cease; and each is made to co-operate with and assist the other, in fulfilling the great ends for which government is ordained.”

The eloquent words of Calhoun unfortunately encounter the def ears of our current posterity. However, its truth cannot be overestimated. He reveals that the ends of government are to promulgate the very notion of co-operation between liberty, albeit of the community and its individuals, and its governing authority. (For the sake of this article I shall substitute power and liberty with government and community respectively). We may well call this the nature of government, as the ends of all things are said to be the objective of their nature.

In addition to Calhoun’s remarks, the origins of his societal design are, and of ought, must be, empirically organic, and reciprocal, as neither the community nor its governing apparatus can sustain itself without the other. Their link is essential for the development of a conservative society. Subsequently, it is acknowledged that by no means of positive cognition did the community construct a governing system in the abstract; no aggregate of reason could be credited with its formation. Its manner cannot be detected through dialectic methods, or through a predetermined scheme positing the political components of a community into empty spaces. The bonds of political society are generated by and through the engine of time. As Eugene Genovese surmised in his book The Southern Tradition: The Achievement and Limitations of an American Conservatism, “… a community’s historically developed sense of right and wrong should be permitted to defy the latest fashions in reasoned speculation until they are empirically established.” It is tradition, longstanding customs and rituals that cement the foundations for southern conservatism to incubate itself. The nature of community and its government, in their tandem conclusion, is human flourishing. So too, the nature of tradition may be marked as southern conservatism.

A governing authority, once established in adherence to the predispositions of southern conservatism, has a reciprocal duty to the community. It not only must prescribe laws to punish criminal activity but must also incentivize a nominal social trajectory for the community to achieve the ends its nature by checking human flirtation with anarchical liberty as Calhoun implicitly suggested in his Disquisition when he warns that “… liberty must not be bestowed upon a people too ignorant, degraded and vicious, to be capable either of appreciating or of enjoying it”. The inhibition of man in his passions is paramount to the furtherance of any social condition, or else no end can be actualized, as the governing structure would be leveled with the advancement of strife and lack of piety within his heart. A people must be willing to subvert their authority inherent among them outside the realm of a community and allocate government to temper the ravages of the non-social being; not necessarily to conform to any supposed arbitrary impositions of the governing body, but to submit to its just authority. A people must acknowledge the flaws of their condition and accept the limitations placed on their liberties as an instrument to advance their nature.

This government is made possible because legitimate political leadership is comprised of the people who established the institution itself. They are a creation of the community and have been brought up experiencing its traditions all the while acquiring a deep understanding concerning the discourse and political arrangement of its fellow members. These have been raised in honor, they are the ends of the virtues entrusted upon them since their conception through social engagement and a furthering remembrance of their traditions.

Plato also contributes this communal configuration, elaborating on the virtues necessary in the conservative community. His Republic depicts four virtues, prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance, designated for the community to exact as well as within the individuals of the same. Notwithstanding the importance of the former three, temperance may be considered the glue that binds the individual, within himself, and the community together respectively. Within the mind, it serves to harmonize the effectuation of the other three. Acting as a covenant within oneself, it emphasizes the performance of moderation along with a relentless pursuance of self-control. Whereas the individual demands control through the faculties of his own conscious, the community demands control through its individuals by its member’s mastery of temperance. This concept is the standing base, a skeletal structure for a conservative society. Perhaps the most important tenant of the southern conservative and his political existence is this notion of a temporal community made up of temporal individuals. This virtue acts as the course arbiter of any community. Mentioned before, the government has a responsibility to incentivize a course trajectory for the community, the nature of temperance is the end of that effort. As the governing authority may be the mind, this virtue may be considered the soul of a conservative society.

All members of the community, therefore, have mastered their virtues, as the conservative tradition insists that the rearing of children must result in a posterity that has absorbed these communal virtues by way of common empiricism. Aristotle also alludes to the concept of this communal arrangement in book two of his Politics, as both the rulers and the ruled are equal and must share each other’s station, ruling and being ruled, as a nostrum to temper the passions of a people betrothed upon this assured level of equity. Book four determines the preconditions for this system to be sustained: a significant devotion to civic duty is necessary as each member of the community, or polis as he refers to it, must be capable of ruling and must have mastered virtue and honor within the social order.

Let it be said further that there is necessity in limiting the scope, both geographically and numerically, when forming a conservative community. Book one of Aristotle’s Politics describes the city as an amalgam of communities, forming together for each other’s benefit, as diversity in the city leads to improved efficacy and self-sufficiency. However, the development of the city does not infer on several communities a narrow channel of political power. Each community is ruled by the others and of itself; their stratified authorities are the makeup of the city which in turn demands that local communities, acting individually, must have acquired the social consciousness obligatory for the creation of a conservative city. This conglomeration cannot be performed on too large a scale. If a people are content to establish themselves as neighbors to those over a tract of hundreds of miles and numbered in the millions, then they have consented to the worst kind of tyranny that could ensue, as said community has sought a unification that can only be ruled by a single central authority. The southern conservative seeks not to unify but to severalize political authority, producing a political structure that, instead of collapsing due to its own weight, catalyzes the ends of human nature and its fulfillment.

Many will still strain to understand the vast components of southern conservatism, and many will still fail to comprehend the sum of its parts. So long its concepts are bound by party platforms or campaign slogans, it will never be realized; the emergence of its tenets will never come to fruition if it remains something to be obtained through abstract rabble-rousing; it will never materialize as a continued faith in a top-down exposition of its axioms; it shall remain a distant relic of the past, as time enslaves our loosening grasp of its understanding; we will never meet its ripple the farther we are from the pebble. Only when Americans recoil from their finalized federal institutions, and conclusively assume their local duties, customs, and warranted social obligations will the southern conservative be born again.