Several months ago, The American Conservative magazine reviewed Forgotten Conservatives in American History, a book I co-authored with Clyde Wilson, and one reader left an online comment about the book. Normally, I do not discuss responses to reviews, but this one caught my eye, in particular because the reader admits that they know little about conservatism yet think they are qualified to discuss conservatism. The reader said, “I have a hard time accepting many of the people noted in the review are real conservatives, in the Burkean sense. My take on Burke, whose ideas I only know from cursory reading, is that he would have been appalled by the South choosing secession, or war, as several of the author’s – and the reviewer – choices advocated. In addition, the authors’ bent towards Southern Civil War arguments on State’s Rights reveals a thorough misunderstanding the volatile and varied arguments that occurred throughout the 13 states during the development of the Constitution.” This quote metis a response for two reasons: 1) As she admits, she has little understanding of Burke, and I believe that the American Burke, John Randolph of Roanoke, would have advanced secession in 1861 and would have recoiled at the revolutionary changes taking place in America in during that time—he already had just a generation before, and 2) the “thorough misunderstanding” I supposedly have about the Constitution reveals that Americans fundamentally believe Lincoln’s “democratic conservative” rhetoric both before and during the War. Most see him as the messiah of American political religion rather than the antichrist, the bridge rather than the chasm between the 1860s and the founding generation. That must change.

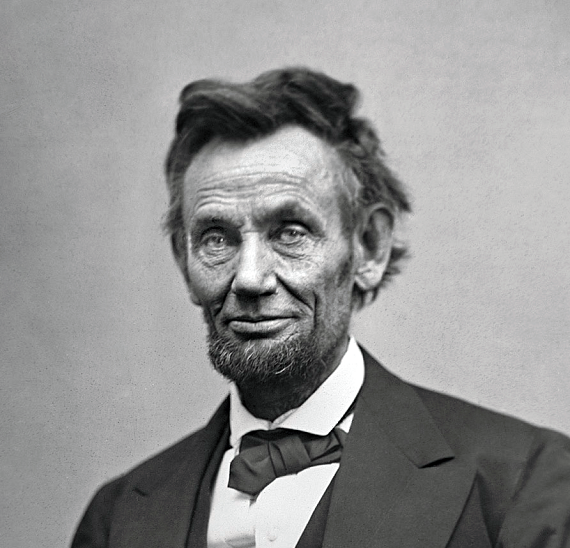

In August 1863, eight months after Abraham Lincoln’s constitutionally dubious Emancipation Proclamation took effect, Giuseppe Garibaldi, the famous Italian egalitarian nationalist, congratulated Lincoln in a fawning letter, writing: “Posterity will call you the great emancipator, a more enviable title than any crown could be, and greater than any merely mundane treasure.” Giuseppe Mazzini, Garibaldi’s Leftist revolutionary mentor and ally, called Lincoln the “benefactor of mankind” and ardently supported the Union cause after the Proclamation. In the United States, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and her allies in the women’s suffragist movement formed the Women’s Loyal League, an organization that Stanton said “voiced the solemn lessons of the war: Liberty to all; national protection for every citizen under our flag; universal suffrage, and universal amnesty.” The League resolved that, “There can never be a true peace in this Republic until the civil and political rights of all citizens are established.”

Charles Sumner, the Massachusetts Senator who suffered humiliation at the cane of South Carolinian Preston Brooks, declared in 1862 that the Southern States “ceased to exist,” even if they should return to the Union. He reasoned that this was the only way to secure universal political and civil rights for all Americans regardless of race, and while he later balked at Stanton’s pressuring to expand the Fourteenth Amendment to include women, Thaddeus Stevens, the “Great Commoner,” embraced the cause. Stevens is a fine example of the “Jacobin” revolutionary spirit during the War. At one time, most historians categorized and described the leaders of the “radical” wing of the Republican Party as “Jacobins.” That has since changed (witness the way Thad and his ilk were portrayed in Speilberg’s Lincoln) and while the radical Republicans attempted to distance themselves from that term, it was no stretch to call them that. Stevens, in fact, was their greatest crusader. His war was to “punish the South” and “remake the South,” but more importantly to remake the United States as a whole. He supported all reform causes expect temperance and pseudo-bourgeois moral righteousness restrictions on foul language. Stevens was alone here. Nearly every radical Republican favored prohibition. Theirs was a Puritanical crusade against both private and public immorality.

Others with nearly as high a profile gladly championed Jacobin reform. As historian Fawn Brodie noted, Horace Greely, the famed newspaperman from New York and later presidential candidate, favored “prohibition, women’s rights, the abolition of sweatshops, free homesteads, and Brook Farm socialism.” The Massachusetts radical Wendell Phillips ran for governor on a reform platform in 1870 that championed “the overthrow of monopolies, the abolition of the privileged classes, universal education…obliteration of poverty…a ten-hour day for factory work and eight hours hereafter,” and equal pay for women. Nearly all opposed capital punishment (except for treasonous Southerners, of course, as radical Benjamin Wade wanted to execute Confederate leaders) and nearly all supported reform of the penal code. Samuel Chase, as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, favored the abolition of the death penalty in all cases except “willful murder.” One historian wrote that, “Their story is the story of American progress,” and each “brought to Washington firmly held ideas of social betterment.”

Clearly, to Stanton, Sumner, Stevens, Chase, Greeley, and even international observers, the War was a revolution, in the same spirit as that which swept France in 1789 and all of Europe in 1848. Abolition was just one component of a comprehensive movement to remake America into a Northern ideologically dominated Puritanical Utopia. But they were not the majority in the Republican Party in 1860, so how did their War become the War? The link is Abraham Lincoln and “American democracy.”

The distinguished historian Frederick Jackson Turner wrote in his monumental work The Frontier in American History:

If the later West offers few such striking illustrations of the relation of the wilderness to idealistic schemes, and if some of the designs were fantastic and abortive, none the less the influence is a fact. Hardly a Western State but has been the Mecca of some sect or band of social reformers, anxious to put into practice their ideals, in vacant land, far removed from the checks of a settled form of social organization….[and] The democracy of the West is deeply affected by the ideals brought by [German and Scandinavian] immigrants from the Old World. To them America was not simply a new home; it was a land of opportunity, of freedom, of democracy. It meant to them, as to the American pioneer that preceded them, the opportunity to destroy the bonds of social caste that bound them in their older home, to hew out for themselves in a new country a destiny proportioned to the powers that God had given them….

Turner viewed Lincoln as a continuation of the American frontier ideal, a conservationist of the ancient democratic order of the American experience brought forward by the American War for Independence. While the Jacobins viewed Lincoln as too cautious, a drag on their Utopian designs, he was, nevertheless, a closet admirer of their zeal and morality. The Jacobins called Lincoln a conservative—as have nearly every American historian since—and in a unique twist, Turner concluded that Lincoln displayed a uniquely American conservatism, one that is more recognizable to Louis Hartz than Mel Bradford or Russell Kirk. Lincoln, Turner said, was a defender of the American principles of democracy against the ruinous doctrines of oligarchy and the ancien regime. Turner believed that the spirit of the West produced Thomas Jefferson (a Southerner), the Declaration of Independence, Andrew Jackson (a Southerner)—who “broke down the traditions of conservative rule…and opened the temple of the nation to the populace”—and Abraham Lincoln. “Best of all,” he wrote, “the West gave, not only to the American, but to the unhappy and oppressed of all lands, a vision of hope, and assurance that the world held a place where were to be found high faith in man and the will and power to furnish him the opportunity to grow to the full measure of his own capacity….Let us see to it that the ideals of the pioneer in his log cabin shall enlarge into the spiritual life of a democracy where civic power shall dominate and utilize individual achievement for the common good.”

Turner, of course, was simply caught up on Cult of Lincoln, a cult that Lincoln himself helped forge during his successful run for president in 1860 and his folksy, home-spun speeches aimed at equating democracy with reform and American founding principles with his—and ultimately those of the Jacobins’—policies. To a group of Germans in 1861, Lincoln said “I am for those means which will give the greatest good to the greatest number,” and in a speech just two days later insisted that the “majority must rule” and the “voice of the people” must be the deciding factor as to “rights under the Constitution.” In New Jersey in 1861, Lincoln attached his impending presidency with the “original idea for which [National Independence] was made.” National Independence is his term. What was Lincoln’s ideal? “Liberty, not alone to the people of this country, but hope to the world for all future time. It was that which gave promise that in due time the weights should be lifted from the shoulders of all men, and that all should have an equal chance. That is the sentiment embodied in that Declaration of Independence.” Clever. This is why the Straussians attach their type of “Conservatism” to the Declaration, because Lincoln did. And Lincoln’s famous Gettysburg Address continued this theme by insisting that the “government of the people, by the people, and for the people” should not perish from this Earth. Lincoln also famously wrote, “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master.” Yet, while Lincoln and other reformers were insisting (incorrectly) that their cause was one of continuity with the founding principles, other Americans, both North and South, contemporary and predecessor, saw the War and the history of America in a different light.

In 1829, John Randolph of Roanoke, the American version of Edmund Burke, made a speech at the Virginia Constitutional Convention typically titled “King Numbers.” He was attempting to thwart proposals made by western county representatives to make the Virginia constitution more democratic. His ruminations on democracy can only be described as prophetic, particularly when compared to the a-historical nature of Lincoln’s appeal to a “democratic” America and the Jacobin preference for reform, what Randolph called “innovation.” And, it must be noted that Randolph requested to be buried standing up and facing west in order to keep his eye on Henry Clay, Lincoln’s political mentor. That makes Randolph’s assertions more sagacious.

Randolph considered democracy to be the bane of society, the final blow to good government, and he classified innovation and reform as the spawn of “obedience to the all-prevailing principle that vox populi, vox dei; aye, Sir, the all-prevailing principles that Numbers and Numbers alone, are to regulate all things in political society, in the very teeth of those abstract natural rights of man which constitute the only shadow of claim to exercise this monstrous tyranny.” He worried aloud about the results of reform, for “I have by experience learned that changes, even in the ordinary law of the land, do not always operate as the drawer of the bill, or the Legislative body, may have anticipated; and of all the things in the world, a Government, whether ready made to suit casual customers or made per order, is the very last that operates as its framers intended. Governments are like revolutions: you may put them in motion, but I defy you to control them after they are in motion.” And in a fearful flourish, one that generations of Americans, particularly those in 1861, should have rendered as predictive:

Are we men…Or are we in truth, a Robinhood Society discussing rights in the abstract? Have we no house over our heads? Do we forget that we are living under a Constitution which has shielded us for more than half a century?—that we are not a parcel of naked and forlorn savages on the shores of New Holland; and that the worst that can come is that we shall live under the same Constitution that we have lived under, freely and happily, for half a century? To their monstrous claims of power, we plead this prescription; but then we are told: nullum tempus occurrit Regi (no time runs against the king). King whom? King Numbers. And they will not listen to a prescription of fifty-four years—a period greater by four years than would secure a title to the best estate in the Commonwealth, unsupported by any other shadow of right. Nay, Sir, in this case, prescription operates against possession. They tell us it is only a case of long-continued, and therefore of aggravated, injustice. They say to us, in words the most courteous and soft…”we shall be—we will be—we must be your masters, and you shall submit.

That should have served as enough warning for schemers, reformers, and innovators that such ideas were disastrous in the long term, yet to the Jacobins in Lincoln’s party bent on revolution, the other side in the debate did not exist. Charles Sumner once slammed his fist on the table in an emphatic denial that any point other than his own had merit. His voice was not soft. The Jacobins intended to be heard. That is revolutionary fanaticism.

Northern Democrats during the War are often painted as dishonest partisans intent on whipping the flames of opposition through grand speeches laced with hyper-sensitive panic about Republican victory. These historians often focus on race—though not every Jacobin favored the quality of the races, nor did Lincoln himself—and they view the results of the war through their own progressive lenses. The war produced salutary effects in their mind, and therefore the Democrats had little to offer other than misguided paranoia. That would be an acceptable position if not for the biting truth of many of their statements.

Common soldiers often complained about what they viewed as a shift in war aims in 1862, particularly those who came from Democratic families. One Indiana soldier wrote that, “If emancipation is to be the policy of this war…I do not care how quick the country goes to pot.” An officer from New York opined that if the war became a crusade for the “black Republicans” for “an abolition war…I for one shall be sorry that I ever lent a hand to it.” Many men deserted rather than wage a revolutionary crusade of abstract human rights. The Union was one thing, but fighting for reform was another. Yet, in fairness, as the historian James McPherson has noted, by 1864, the war had taken a revolutionary tone for many of the common soldiers in the North. Some still opposed the reformist agenda, but most (McPherson concludes probably 80 percent) thought emancipation should be a war aim. As one Michigan solider said, “After this war is over, this whole country will undergo a change for the better…Abolishing slavery will dignify labor; that fact of itself will revolutionize everything….” This was Lincoln’s democratic army at work. Without the Union army vote, he would have been in trouble in the 1864 election. As in France, the Union levee en masse “revolutionized everything” with blood and steel.

Yet, astute thinkers in the North and South understood the score. Samuel S. Cox, a Democratic representative from Ohio, and firm Lincoln opponent, warned of the consequences of unchecked reform:

Extreme men drag the moderate men with them. The devil, it is said, holds his own by a hair. He has entered into this majority as he entered into the swine; and they will, by diabolic impulse, be driven at last into the sea. At last—but when is that time to come? When the country is ruined?…They will not halt until their darling schemes are consummated. History tells us that such zealots do not and cannot go backward. Robespierre, the gentle judge at Arras, in 1783, resigned rather than condemn a criminal to death. In ten years after, filled with the enthusiasm of Rousseau, he claimed for the blacks in the French colonies a participation in political rights, and exclaimed, not unlike members here, “Let the colonies perish, rather than a principle!” But he was the same Robespierre who led the Jacobins to demand the King’s head in 1792, who established the reign of terror, and whose motto was, “that to live was a crime.” He could take no step backward. Onward, onward from excess to excess, until his name became the obloquy of the world. Only his own death, lay the same terrorism, ended his terrible rule. The same result took place at Rome, in the time of Gracchus. It does so everywhere when passion is driven to excess. Our only safety now lies in moderate and patriotic counsels, not rash and vindictive action….

United States Senator James A. Bayard of Delaware frequently characterized the Republicans as Jacobins similar to those who initiated the Reign of Terror and that the war was one of extermination of the Southern people. He was most distressed over the “Puritans and Quakers” who ran the government both in Washington and Delaware. In 1862, he wrote that “I fear Lincoln will give us a more radical [cabinet], for Beecher declared the other day in Boston, that ‘God was a radical and the devil a conservative.’ What a clergyman!”

This charge against Northern Puritanical zeal was commonplace among critique of the Republicans in the South, both before and after the war. Reform was the centerpiece of their crusade, and while the perception exists that they never succumbed to the excesses of the revolution, over 300,000 Southerners who baptized their fields of revolution with blood would disagree. The Republicans did not guillotine Southern leaders, but they certainly emasculated the South and over time have transformed the nature of the federal republic. That is their legacy.

Writing one year after the conclusion of the war, the Southern newspaperman Edward Pollard wrote that in 1861 Abraham Lincoln “announced a great political discovery. It was that all former statesman of America had lived, and written, and labored under a great delusion; that the States, instead of having created the Union, were its creatures; that they obtained their sovereignty and independence from it, and never possessed either until the Convention of 1787.” This, Pollard concluded, gave Lincoln the ability to woo America into a false religion of democracy, a democracy that led to disastrous war and striking political revolution, not in the South as he claimed, but in the North, a revolution he helped begin. Lincoln was the Duke of Orleans, the tragic figure who hoped to quell a revolutionary spirit only to meet his demise through assassination, the Duke by decapitation, Lincoln through a bullet. America, the founders’ America, and the Constitution as ratified by that generation, were shredded by the Jacobin war machine.

Looking back, we can see the seeds being sewn long before 1861, but it was the zeal of the Jacobins that made it possible. Perhaps if Americans had listened to the founding generation, then the cruel war never would have happened. They understood that a Union must be for specific purposes and never consolidated. As Benjamin Randall of MASSACHUSETTS said in 1787, “if the states were consolidated…it would introduce manners among us which would set us at continual variance.” The Jacobins took care of that by waging a war of revolution and extermination. Emancipation was but one component of a larger plan at consolidation and centralization with the ultimate objective being the recreation of the United States. Barack Obama has not been incorrect when he has suggested that his administration continues to remake America. That process has been ongoing for 150 years. We are living in the end result of Lincoln’s American Revolution. Obama is simply wearing his red Republican kepi.