There is in some of our libraries a certain book which the writer of this article ventures to believe is not generally as familiar as it should be to the student of politics. For himself, he chanced one day, several years ago, to blow the dust from off its time-worn binding and nine hundred dreary-looking pages of fine print, to read it through with zeal, and he opens it with interest to-day. It depicts the critical moment of the fierce struggle which was waged between the democratic and aristocratic forces of Virginia two generations ago; but the principles involved in that struggle belonged to no one State then, concern us to-day, and will concern generations to come.

The strategic points of the struggle in Virginia were the qualifications for suffrage and the basis of representation in the General Assembly. In the early days of the colony, when a few men were jostled together in the hardships of settlement, all freemen were expected to vote. In 1654-5 the suffrage was restricted to housekeepers and to one person in a family; but the next Assembly allowed all freemen to vote again, provided they did so fairly and in no tumultuous manner! In 1670 it was again restricted to freeholders, housekeepers, and taxpayers, the Assembly declaring that many freemen, who had come from Europe as indentured servants and had no property, having little interest in the country, did often make tumult at elections rather than provide, by discreet voting, for the conservation of peace. So, with the exception of a few months during Bacon’s Rebellion, the suffrage remained limited, as in England, to those who by their estates were deemed to have sufficient interest in the community to tie them to endeavors for the public good, the unit of property, to give a vote, being finally fixed at fifty acres of unimproved land, or twenty-five acres of improved land, with at least a small building, or a house or lot in a town. There was the interesting addition that in Williamsburg and Norfolk, the only towns of any size, resident housekeepers could vote, provided they were worth fifty pounds or had served as apprentices for five years to some trade in the town. As to the basis of representation in the General Assembly, that was early fixed, when the counties along tidewater were reasonably alike in population and interest, at two delegates from each county and one each from several corporations.

In the spring of 1776 a convention which had been chosen to serve as a temporary government for the colony, was called on, by practical separation from Great Britain and the absence of any constitution, to prepare a plan of government. Within a few weeks it adopted, unanimously, a Bill of Rights and a Constitution. The Bill of Rights embodied the spirit of George Mason and Thomas Jefferson, believers in the people, in phrases which are familiar to us all. All power, it said, was derived from the people; all men giving sufficient evidence of permanent interest in the community should have the right of suffrage; and the right to reform government was inalienable in the majority of the community. The Constitution which followed expressly provided that the suffrage should remain as it was. Representation in the House of Delegates remained as it was, also, (excepting a few small corporations which were dropped) although great differences had grown up between the smaller and larger counties. A Senate was added of twenty-four members from as many districts. The Governor was to be elected by the Assembly.

The State of Virginia, leaving out that part which became Kentucky, was about equally divided by two mountain ridges with a narrow valley between them. By 1776 this valley held a considerable population, but not till the close of the century did the region west of it, the Trans-Alleghany, begin to grow fast. By 1810, of the white population of the State, which was about 550,000, some 212,000 lived west of the Blue Ridge, in the valley and Trans-Alleghany region. Between the east and west of this great State, the distance from the Ohio to the sea being two hundred and fifty miles, communication was difficult. The ways of life most typical of the sections were also far apart. In the east, society was generations old, there was much wealth, chiefly in slaves, and wealth and cultivation predominated in things social and political. By 1810 there were 392,000 slaves, most of them east of the mountains. West of the mountains there was little wealth, and but little of that was in slaves, and ways of living were plain. On the upper Potomac and the Pennsylvania border, there was an increase in white laborers, many of them Germans.

During these years, the inequalities in representation had become remarkable. There were a dozen of the old tide-water counties, with many slaves indeed, but with less than three thousand whites, each ; while a dozen of the newer counties had each several times as many whites but comparatively few slaves. Of the twenty-four Senators, four only, from the west, represented over one-third of the whole white population. A minority of voters controlled the State. More striking still was the limitation of the suffrage — over half the adult white males could not vote. The case was recorded of one company of seventy men who enlisted in the War of 1812, from an eastern county, of whom only two could vote. The roll of freeholders entitled to vote, said Jefferson, did not generally include the half of those on the rolls of the militia or of the tax gatherers.

From all this came much dissatisfaction, that kept growing more and more intense. Calls for an extended suffrage came from all parts of the State. An entire readjustment of representation was demanded by the west and by several of the populous border counties. After 1790, hardly a session of the Assembly passed without petitions for reform, and resolutions and bills were introduced in vain. In 1816 a Reform Convention was held at Staunton, in the Valley, of delegates from a number of neighboring counties, asking that the law of the land should voice the will of the majority. But the only step gained — and barely gained, for the body of eastern members opposed it — was the equalization of the Senate districts by white population, as given in the census of 1810. Again, in 1825, a Reform Convention was held at Staunton, attended by some eighty delegates. Finally, in 1828, a bill was secured for taking the sense of the voters on the need of a convention, and 21,896 asked for it and 16,646 opposed it.[I]

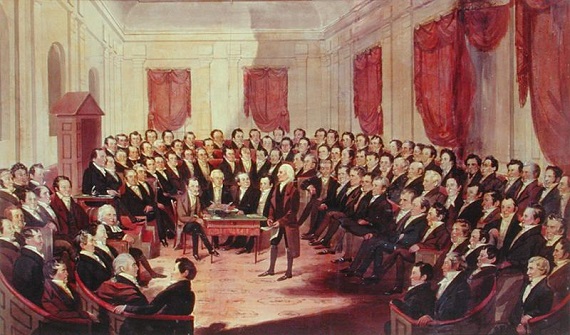

The Convention that met in Richmond in October, 1829, was a very exceptional body of men. The choice of them had not been limited to local districts. Its president was James Monroe, on the floor were James Madison and John Marshall. The roll was largely made up of men who stood highest in Virginia, and were known throughout the land.

Proceedings began with the acceptance, verbatim, without opposition, of the Bill of Rights of 1776. But there, at once, unanimity ceased, when principles were to be put into practice. Two radically opposite tendencies were shown, and the issue direct was joined over the rightful source of power in the State. The one party said, the white population; the other, that population and wealth combined. The latter intrenched behind old usage, regarded their opponents as radicals indeed. “Give us,” said Mr. Benjamin W. Leigh, of Chesterfield, one of the leaders from the east, “give us some reasons for this new scheme which has respect to numbers alone and considers property as unworthy of regard; some reasons which may excuse us in our own self-esteem for a tame submission to this, in my opinion, cruel, palpable, and crying injustice! Let us have at least the color of reason; something to gild the pill and disguise its bitterness, to save us from the contempt of the present and the assured curse of posterity if we betray its interest! Give us, not mere abstractions, but reasons, based on the conditions of this State, why we should submit to what I cannot help regarding as the most crying injustice ever attempted in any!”

A member from the Valley rose, in reply, with the Bill of Rights in his hand. “Are these principles,” he said, “for which our fathers sacrificed so much, mere abstract principles? On the contrary, they are the principles which alone give a distinctive character to American institutions. The Constitution of 1776 is, indeed, contradictory to these, but it was framed by practical men, and to have tried to change, during the commotion of that time, the customs of a century, would have been unwise. In 1781 Mr. Jefferson urged Virginians, so soon as they had leisure, to intrench in good forms the rights for which they had bled.” “Let us not forget, sir,” replied Judge Upshur, from the Eastern Shore, “that government is a practical thing, and that experience is the best guide. There are no a priori rules of nature for it. If mere numbers are to rule, why are not women included in the suffrage, or the drones that live on the industry of others? There is a majority in interest as well as in numbers. For more than half a century the political power of Virginia has been in the hands which now hold it, and without abuse; why then take it away?” “The Constitution of 1776,” said Mr. Philip Doddridge, “was not an agreement -made by all for the benefit of all, but was made by a part of society, the freeholders, and to a great degree for their own benefit. Our opponents would draw the conclusion that he who brings the most property to be protected is entitled, to the most influence in government, instead of the very obvious conclusion that he should be subjected to the greatest share of the expenses of its protection.”

Principles and practice alike were considered. If one member referred to the new States, Alabama and Mississippi, sister slave States, but with their broad basis of general suffrage and white representation, another showed the Carolinas and Georgia, with greater protection to property interests, to say nothing of free States like New Hampshire and Massachusetts. “Talk of experience of our sister States,” said Mr. Barbour, of Orange, “so far as experience goes, it is in our favor; experiment is against us. Talk to me of experience of States which came into being but yesterday! Why, sir, I have myself assisted in Congress in the creation of a half dozen of them!”

“New York State,” said Mr. Leigh, “ has adopted a general suffrage, but if the city of New York continues to grow in future as it has been growing, the State will rue the day it gave the city such representation, out of mere respect to theoretical and contempt of practical equality.” “Look at every State,” said Governor Giles, “where suffrage has been made universal, and you will find universal disorder, intoxication, and demoralization of all sorts.” So discussion ranged from forms of government in republican Rome to the last election inNew York. “As I have been listening here,” said John Randolph, of Roanoke, “ I have thought myself in the House of Representatives, at one time listening to the debate on the tariff; at another, to the debate on the Missouri question, and sometimes, I fancied, to both being debated at once. Are we met to consult over affairs or to discuss rights in the abstract? Do we forget that we are living under a Constitution which has shielded us for half a century? That we are not a parcel of naked savages on the shores of a Pacific island?”

Underlying all, was the practical question of political power in the State of Virginia. And when representation of wealth was demanded, all thought instinctively of the great slave-holding interest which paid nearly a third of the State revenues. “ I am satisfied,” said ex-President Monroe, “that if no such thing as slavery existed, the people of the east would meet their brethren of the west on the basis of a majority of the free white population.” “Our opponents say to us,” said John Randolph, of Roanoke, “in words the most courteous and soft (but I am not so soft as to swallow them), ‘We shall be, we will be, we must be your masters, and you shall submit! You have property but we have numbers! ’ And to whom do they hold this language? To dependents, weak, unprotected, and incapable of defense? Or is it to the great tobacco-growing and slave-holding interest and to every other interest this side of the Ridge?”

To this the west answered through Mr. Doddridge: “Do we misrepresent or exaggerate when we say your doctrine makes us slaves? We may still pursue our own business and obey our own inclinations, but so long as you hold political dominion over us, we are slaves. We are a majority of individual units in the State, and your equals in intelligence and virtue. Yet you say we must obey you!” So sharp, and of such a sectional character were the differences. Gould a Constitution ever be formed which would promise peace?

As to suffrage, the plan of the western men which received greatest consideration from the Convention, was that suffrage could be exercised by all white men (paupers excepted) resident for two years in the State, and for one year preceding in the county, who had been enrolled in the militia, if subject to military duty, and who had paid their taxes for that year. This was defeated at first by fifty-three to thirty-seven. Madison, Monroe, and Marshall all voted against it. Brought forward again with the proviso that the tax should be no mere petty poll tax, it was lost, on two trials, by a tie vote. The western men voted solid, supported by a few from the southeastern slope of the Blue Ridge and from the Eastern Shore across the Chesapeake. Conservative eastern leaders raised a warning voice against a possible overturning of the accustomed basis of society by one or two votes. The broad suffrage men finally could secure no more than the extension of suffrage to resident housekeepers who were heads of families and taxpayers, for a year preceding the election.[II]

Over the basis of representation the struggle was fiercer still. Motions to base the House of Delegates on white population and taxation combined, or on Federal numbers, made by eastern men, were lost, all members voting, by two votes. “We have arrived,” said Mr. Nicholas, of Richmond, “at an awful period in our deliberations.” And John Randolph, of Roanoke, declared that if such a monstrous tyranny as a white population basis, without regard to property rights, should be imposed on the State, and if he were a young man, he would leave the State — he would not live under “King Numbers”! The venerable Mr. Monroe, from a county between east and west, urging mutual concessions, suggested a white basis for the House and a mixed basis for the Senate. “We,” he said, “unlike the ancient republics, have no privileged orders; the property of the country rests on the people alone.” But the eastern leaders would not follow him. Evidently no Constitution could be secured without concession. For that the western men urged a white basis for the House and federal numbers for the Senate. On the test vote, all members present, this was lost by a tie. Then a few, not unwilling to leave a plan which recognized property representation, or else, with Mr. Madison, moved by a spirit of conciliation, went over to the plan — based on no principle, and opposed by the west — for an apportionment of representation by several sections of the State, east and west. Every ten years the apportionment within these divisions might be changed “by the legislature by majority vote, but any reapportionment throughout the whole State must be by concurrent action of two-thirds of the Senate and House. This provision had been suggested by Mr. Madison to prevent the need of another convention for future reapportionment, and had been adopted by a close vote. Western men disliked it. “Why,” said one, “are you so afraid of the people? Is this Constitution to be such an anodyne that it will keep them asleep forever?”

Such, in brief, were the chief movements in this battle over the Constitution. Meantime several noteworthy skirmishes had taken place along the lines. Mr. Doddridge moved that the Executive should be an independent coordinate branch of the government, unhampered by a council, elected by the people, and responsible to them. He was seconded by a Piedmont member, who stated that eighteen States then elected Governors by the people and only six by the legislatures. This motion was at first lost, by the casting vote of the chair,1 but was afterwards carried by a majority of four, and later still, when concessions were deemed more necessary, was reconsidered and turned down by the same majority.

As to qualifications for election to the General Assembly, a select committee advised that those who could vote should be eligible for office. On Mr. Leigh’s motion, despite the opposition of the general suffrage men,[III] [IV] this was restricted to resident freeholders. “ Why,” said one, “ why shut out leaseholders and housekeepers, whom you now allow to vote, from choosing who shall be their representatives. There seems to be a strange dread of giving power to the people ! ” A resolution that there should be in the Constitution a provision for amendment, found only twenty-five supporters. “ I would as soon think,” cried John Randolph, “ of introducing a provision for divorce into a marriage contract.” When the system of county courts was spoken of—those family tribunals, with their mild and patriarchal jurisdiction, as one of their defenders called them — a suggestion was made that small salaries might be paid in the west, to cover the travelling expenses to which respectable farmers, who were often magistrates there, were subjected. But Mr. Leigh and other eastern men declared that such a change would revolutionize and mar the entire system. Mr. Leigh went so far as to declare that he did not believe that men who were obliged to labor daily for their living, could ever enter into political affairs. Alexander Campbell, from the west, the founder of the Church of the Disciples, tried to get some encouragement from the Convention for popular education. But eastern men opposed, John Randolph cracking his whip vigorously. It was such constant opposition to trusting the people that made Mr. Campbell exclaim:

“ I did hope that we would feel a little more in accordance with the progress of improvement and the spirit of the age, than to put forth all our energies in a contest about mere local interests, which a few years will change in defiance of all our efforts. For it is decreed that every system of government not based upon the true philosophy of man, not adapted to public opinion, to the genius of the age, shall fall into ruins.”

During the discussions, fear was several times expressed, that protracted dissentions in the State might lead to its division. Mr. Leigh went so far as to declare twice, at least, that the struggle was one which, in any other country on earth, could be decided only by the sword, an issue which would be prevented here by the influence of the Federal Government. “Our government,” said Mr. Doddridge, in answer, “is an elective republic, and we mean to leave it so. The ‘numbers’ that we speak of are of ballots, not bayonets.” The Constitution adopted in convention by fifty-five to fortv-one,[V] was approved by a large majority of those who chose to vote on it under its extended suffrage. Disapproval was chiefly in the west. John Randolph, of Roanoke, predicted that it would not last twenty years on account of its too democratic tendencies. It was superseded just twenty years after, by a Constitution much more democratic.

Such, in short, is the story of this dreary-looking book, which usually gathers the dust on some library shelf. Whatever our sympathies — whether we should have stood with Leigh or Doddridge in the arena of the capitol at Richmond— it certainly has a lesson for us. From it our thoughts turn back to the compromises of the Federal Constitution, and forward to the great struggle of the slave, power for self-protection, and to Lincoln’s appeals to the principles of the Declaration of Independence. But the study of history, like everything that is worth anything, is chiefly of value for the present and the future. Questions of suffrage and representation are being asked to-day — the extension of suffrage to women, its restriction by educational or property qualifications, the justice of minority representation, the wickedness of the gerrymander, practical questions which should be answered. Theories of government^ doctrines, again and again come into conflict with existing conditions. And the motives which will influence men in making answer to political questions are the same yesterday and to-day. With the few, a wise foresight and lofty unselfishness; with the many, consciously and unconciously, the power of interest or wealth, in one form or another, and the fetters of custom. Human nature being the same, history repeats itself.

This article was originally published in the Vol. 4, No. 3 (May, 1896) edition of the Sewanee Review.

[I] The Assembly then provided that the Convention should consist of four members from each Senatorial district, although those districts were based on the census of nineteen years before, and the increase of population in those years had been four times greater in the west than in the east.-

[II] A motion to strike out this extension to housekeepers was easily defeated by fifty-five to forty. Marshall voted to strike out, Madison to keep it. ‘

[III] On this first ballot Madison voted “aye Monroe and Marshall, “no.”

[IV] Marshall and Madison voted for Mr. Leigh’s motion. Monroe had resigned.

[V] The nays were forty, but Mr. Doddridge, who was ill, would have voted “no.”