It’s strange to think that until 1962 — when the Houston’s Colt .45’s enjoyed their inaugural season as an expansion team — the only baseball teams in the South were on its northernmost borderlands: Baltimore, St. Louis, and Washington, D.C. Of course, like all professional sports, baseball is about money, and profits are easily made in densely-populated urban centers, of which the South had few in the professional game’s first half-century. In 1950, the biggest town in the Deep South, New Orleans (pop. 570,000), was only the sixteenth-largest city in the nation. Indeed, at that time, Rochester, New York, had more people than Atlanta.

Nevertheless, Dixie’s baseball pedigree is ancient and venerable, even if Southern states in the antebellum era ignored baseball in favor of cricket (amusingly, some Southern newspapers claimed that baseball seemed too “Yankee” and was antithetical to Southern culture). New Orleans was however an outlier: in part because of its economic connections to the North, the city had fifteen baseball clubs on the eve of the Civil War. During the war, many Southerners were exposed to baseball via prisoner-of-war camps, both those controlled by the Union and the Confederacy. The lithograph “Union prisoners at Salisbury, N.C.,” by Act. Major Otto Boetticher, shows captured Union soldiers playing baseball in a Confederate-run POW camp in 1862.

Soon baseball’s popularity was rapidly spreading among Confederate units. A Union soldier at an encampment in Falmouth, Virginia, described watching Confederate soldiers play the game from across the Rappahannock River. Confederate troops had difficulty obtaining good baseballs and bats, often resorting to makeshift equipment, their bats made of wooden boards or fence rail, their balls sometimes “nothing better than a yarn-wrapped walnut.” By 1864, almost every Confederate regiment was playing the game. When Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House, both Union and Confederate armies played baseball to pass the time. Baseball was lauded by many as an effective means of reconciliation in the post-war era.

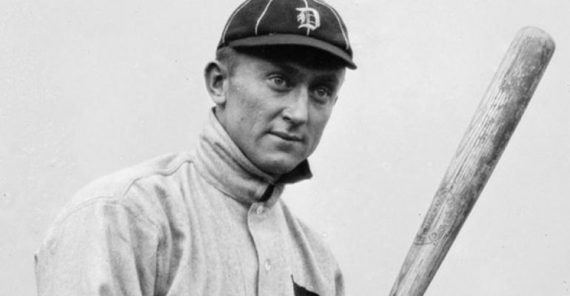

In the years that followed the South bequeathed to the game many of its greatest early legends. The Georgian Ty Cobb — who, contrary to Ken Burns’ depiction in his 1995 documentary, was in favor of racial integration in the sport — was arguably the best hitter the game ever saw, and set ninety records. Prior to a May 1925 game against the St. Louis Browns, Cobb reportedly told a sportswriter: “I’ll show you something today. I’m going for home runs for the first time in my career.” Cobb went 6-for-6, including three home runs. I’d take Cobb over Babe Ruth any day.

Other early Southern stars included Rogers Hornsby (Texas), Tris Speaker (Texas), Shoeless Joe Jackson (South Carolina), and Lefty Grove (Maryland). The integration of baseball following Jackie Robinson’s first season with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947 ushered in a new era of great black ballplayers from the South, including Hank Aaron (Alabama), Willie Mays (Alabama), Monte Irvin (Alabama), Lou Brock (Arkansas), Larry Doby (South Carolina), and Ernie Banks (Texas). Many of the best collegiate baseball programs in the nation are also Southern, including Texas (2nd in the all time wins list), Florida State (5th), Clemson (8th), North Carolina (9th), Texas A&M (11th), Mississippi State (13th), Alabama (16th), Miami (18th), South Carolina (19th), and Louisiana State (t. 20th), among many others.

Though much is made of the South’s affection for football and those “Friday night lights,” baseball has always competed for a place in our heritage and identity. Thankfully, Major League Baseball in the last half-century has recognized that Southerners love their baseball as much, or almost as much, as they love their SEC football. Besides Houston, St. Louis, Washington, D.C. (sadly not much of a Southern city anymore), and Baltimore (they still play John Denver’s “Thank God I’m a Country Boy” at every game), there are now teams in Atlanta, Arlington (Texas), Miami, and Tampa Bay. Of the last, George Will in his bestseller Men at Work explains: “What the Chesapeake Bay is to crabs, Tampa is to baseball talent: a rich breeding ground known for both quantity and quality.”

There is also something undeniably Southern in baseball’s peculiarities and aesthetics. Bunting, knuckleballs, and stealing home — sadly elements of the game far less common in our time — all reflect creative tactical risks reminiscent of a general deciding to divide his outnumbered army to outwit and outflank the enemy. And, like Chancellorsville, sometimes the gamble pays off. The Oakland Athletics’ Ramon Hernandez in the first game of the 2003 ALCS laid a perfect, game-winning bunt against the Red Sox. Hall-of-Famer Phil Niekro of the Atlanta Braves won 318 games as a knuckleball pitcher. The Dodgers’ Jackie Robinson successfully stole home against the New York Yankees in the 1955 World Series.

Or consider differences between the National and American Leagues, not only in regards to strike zone (purportedly because of a difference in umpire equipment), but more controversially whether or not both leagues should have designated hitters for pitchers (the NL has thus far remained stubbornly resistant to this change, done in 1973 by the AL). Baseball fanatics like George Will, for example, have argued in favor of bringing the DH to the NL. Yet what such progressivists (including the Whiggish Will) fail to understand is that part of the charm of baseball derives from regional differences.

Consider this Southern analogy. Many, rightly, have strong opinions about the best barbecue: vinegar-based North Carolina, mustard-based South Carolina, tomato-based varieties of Memphis or Kansas City, or the mayonnaise-vinegar mixture of Alabama. Some prefer pulled pork, others brisket, pork shoulder, or even ham or chicken. Yet I think few Southerners would want their favorite to monopolize the market and eliminate their competitors, so that regional distinctions were obliterated. South Carolina BBQ is certainly not my favorite — yet by no means do I desire it eliminated. We preserve cultural differences precisely as a celebration of a local character, and because we appreciate the variety of such parochial traditions.

This is also why many baseball lovers are suspicious of the contemporary obsession with data analytics, which tends to vitiates its beautiful imperfections. Former Red Sox executive Theo Epstein recently admitted: “The executives, like me, who have spent a lot of time using analytics and other measures to try to optimize individual and team performance have unwittingly had a negative impact on the aesthetic value of the game and the entertainment value of the game in some respects.” By using computers and algorithms to carefully analyze every human activity on the diamond, the game loses some of its mysterious luster. Even Will acknowledges: “Baseball people love numbers, but there are limits to what can be quantified, even in baseball.”

Over-reliance on technology points to another area where baseball and Southern identity overlap: conservatism. Will notes that conservatism is defined by an acknowledgment of limits: on the human person, on society, and even on technology. Conservatives like limits not necessarily because we are “narrow-minded,” but because we understand that boundaries help protect us, and direct us towards authentic, objective goods. We want the game we played as children and watched on television to remain identifiable with what we teach our children. I am currently the coach for my older son’s little league team, and am training him the same way my father trained me thirty years ago.

Restraints also remind us of our fallenness and instill humility. The best hitters in the game fail two-thirds of the time. Even the very best pitchers periodically get shelled. “Baseball is a game of failure,” says Will, rightly. To succeed in such a game requires virtue, patience, and resilience. The progressional game goes for six months of the year (and more if your team goes deep into the playoffs). It takes a tremendous toll on even the most athletic bodies, strongest wills, and penetrating minds, rewarding the wise and discerning rather than the brash and arrogant.

Baseball looks askance at rule-breakers, which is part of the reason why so many purists demand “records” set by Roger Maris, Mark McGwire, and Barry Bonds have asterisks next to them, either because of changes in the game, or flagrant cheating. Players routinely punish those who violate its ancient, venerable traditions. When Texan pitcher Roger Clemens realized an opposing player on second base was stealing signs, he stepped off the mount, walked to the runner, and said “If I ever see that again from you or anybody on your team I’m going to bury the guy at the plate.” (To his shame, Clemens himself was implicated in the steroids controversy).

Hitters, until recently, were regularly beaned for bat flipping, because such behaviors were viewed as undermining the humble customs of the sport, which discouraged being a “show-off.” Indeed, since “Casey at the Bat” was praised for his Christian charity, baseball has honored the gentleman over the scoundrel, the quiet endurance of Cal Ripken over the bombast of Albert Belle. We love the players who retain that “regular Joe” persona, the everyday grinder rather than the over-hyped publicity of the overpaid, superstar celebrity with the big Yankees contract.

Brion McClanahan last year wrote to me: “If the Southern tradition dies, America goes with it.” I think one might say the same thing for baseball. The game, in all its curious ceremonies and delightful idiosyncrasies — including the absence of a clock, which Will calls a “product of the preindustrial sensibility” — must be jealously protected. New generations of Americans must be properly catechized to appreciate and understand the wonderfully simplistic truth spoken by professional manager Tony La Russa: “There’s a lot of stuff goes on.” As another season begins, I pray we take a break from the frenzy of our socio-political distemper to see that stuff.