From the 2011 Abbeville Institute Summer School.

The topic I chose was “Douglas Southall Freeman, a Southern Historian’s Historian.” But I could have all kinds of meanings. It could be he’s a Southern historian’s historian, or he’s a Southern historian’s historian. He’s also a Southern historian’s military historian, because most of the topics that he wrote about were military oriented. He’s just really, really good and I cannot recommend Dr. Freeman strongly enough to anybody. I want you to bear in mind an image you’ve all seen, the image of Preston Brooks beating the snot out of Senator Sumner, where Senator Sumner is laying on his back and he’s holding up a pen, trying to defend himself with a pen, as Preston Brooks is wailing on his sacrilegious, rude head. I mean, back in the day, if you say that my cousin or my kinsman consorts with prostitutes, you should expect a butt-whoopin’. That’s just going to happen. Anyway, bear that image in mind, though, and I want you to transpose some of the figures. The person laying on his back, defending his cause with the pen is Dr. Freeman, and the person doing the wailing is President Lincoln or the federal government personified. The fact remains, though, that Massachusetts left that seat empty until Senator Sumner was able to recuperate to the point he could come back to the Senate. And it was a testimony to the brutality of, Preston Brooks, etc. The difference between the two, though, in this analogy is that is that Southerners fought back and Dr. Freeman did not leave the chair empty. Dr. Freeman occupied the space by what he had to say.

If my style is somewhat laconic, I apologize beforehand. The army writing style is active voice, short words and short sentences. It’s choppy, etc., so you’ll have to bear with me. I’ve got twenty-six years of programming I’ve got to undo, so I don’t know how to write a complex sentence anymore. What I propose to do is offer a short catalogue of Freeman’s major works, a brief biography of the man, and some characteristics of his life, and a critique of his work, and some quotes in extenso so that we can all get a feel for his style, which I think is absolutely brilliant. His first major work, published in 1908, is called A Calendar of Confederate Papers, and I’ll talk about what that consisted of in a moment. Calendar put Freeman’s name in the scholarly press, which led him to be asked to write a book that became Lee’s Dispatches, which is a collection of dispatches to and from General R. E. Lee during the course of the war that they thought had been destroyed. But it turns out they weren’t, and Freeman was asked to edit and publish those, which he did. That was very well received and in turn led to Scribner’s Publishing asking Dr. Freeman to write a biography of Robert E. Lee, which is called R.E. Lee: A Biography. That was published in 1934, nineteen years after he started it. There’s sort of a trend here with writing multi-volume books that take decades to write. In 1939, he published a book called The South to Posterity, which is a collection of speeches he delivered at Montevallo College, which is now the University of Montevallo in Alabama. He was asked to give a series of lectures, and he did, and then they turned around and published them. Dr. Freeman’s next major work was Lee’s Lieutenants, in three volumes that were published in 1942, 1943, and 1944. His final work was George Washington, which he finished writing in 1954. He died the day he completed volume six. His research assistants finished volume seven and fortunately won a Pulitzer.

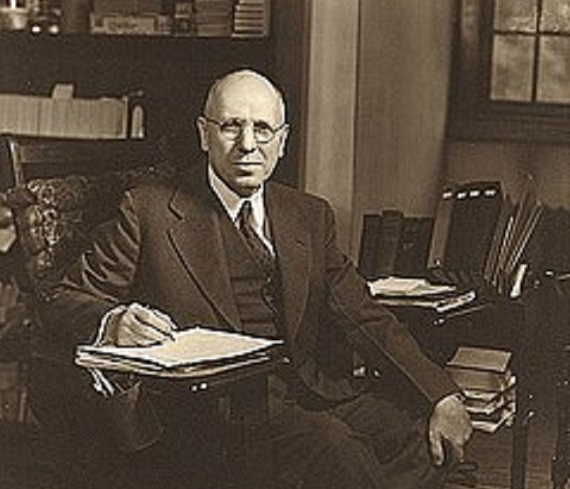

Now for his biography. Douglas Southall Freeman was born in Bedford County, Virginia, in 1886. He was the son of Walker Freeman, a Confederate soldier who at the age of 17 was twice wounded at Seven Pines. Have you ever seen the battle honours for Seven Pines? It’s the only battle I’ve ever seen in American military history that has an exclamation point at the end of the battle honours. Even though there’s worse battles, nobody else has an exclamation point but Seven Pines. After recuperating Walker Freeman rejoined the 34th Virginia Infantry under General Henry Wise’s Brigade, which was deployed to South Carolina, served in the Charleston area in September of 1863, and then went back to Petersburg in June of 1864. Walker Freeman served there until retreat took him to Appomattox for the end of the Army in Northern Virginia. Well, Walker went home to try to rebuild his fortunes as a young man and still had his future in front of him. He opened a dry goods store in Lynchburg. It was in Lynchburg that Douglass Southall Freeman was born in May of 1886. When Walker Freeman’s business went under, he took a job with an insurance company and made a solid reputation for himself. Lynchburg at the time was the home of Jubal Anderson Early, the Lost Cause Curmudgeon, a man who never married but was grinding axes until the day he died and had a pretty surly reputation. General Lee affectionately called him “My Bad Old Man.” Well, the local wags used to tell young boys that General Early used to eat a young boy for breakfast, so Douglas Southall Freeman remembered running past that house as a lad because he was afraid that General Early would grab him and have him for breakfast. In 1892 the Freeman family moved to Richmond and young Douglas began a lifelong love affair with the former Confederate capital. Douglas attended John McGuire’s private school, where Mr. McGuire would lecture his students on character and he would use episodes from the life of General Lee as the example for whatever lesson was going to be taught. Obviously, Freeman was impressed by this and took it aboard his own character. Freeman went on to earn a B.A. at the University of Richmond. While a student at Richmond, his father took him to a reenactment of the Battle of the Crater. Now, nowadays, there are reenactments all over the place, but at this particular reenactment there were Confederate soldiers in the reenactment who had fought in the actual battle, and this event made an incredible, life-changing impression upon young Douglas Freeman. These were the survivors of Mahone’s Brigade. One of my ancestors was in that brigade, among the men who had saved the Confederacy on that day. Freeman was overawed by the spectacle, and he said himself that this kind of defined his life for the next forty or fifty years. He wrote in his diary: “If someone does not write the story of these men, it will be lost forever. I’m going to do it.”

Upon graduation, Freeman was admitted to Johns Hopkins to do his graduate work. His dissertation, which unfortunately was lost in a fire at Johns Hopkins, was on secession in Virginia, specifically the political machinations of secession. While still working on his dissertation, Mrs. Kate Miner of the Confederate Memorial Literary Society asked Freeman if he would undertake a scholarly job for the Society.[1] This job was to assemble what is now called A Calendar of Confederate Papers. They had a bunch of papers that the ladies had assembled from all over the South., and they needed someone with a scholarly background to arrange them and annotate them, etc. Freeman did that, and the book that was published was eventually 615 pages. It received some excellent scholarly reviews. His success in this endeavor led to another remarkable opportunity when Mr. Wimberly Jones DeRenne of Savannah asked Freeman to edit and publish a collection of letters to and from General Lee during the war. These papers had long been believed to have been destroyed, so Freeman was eager to take on the project. This came to light after the publication of the Official Records of the War the Rebellion, so that they weren’t included in that massive collection. There was thus a great scholarly value to these works and Freeman was ecstatic to have the opportunity. So, he took it on while simultaneously taking on the job as an editor of the Richmond News Leader, which was the afternoon paper for the old Confederate Capital. Freeman retained his relationship with the News Leader for most of the rest of his professional life. Freeman published the book, called Lee’s Dispatches, in June of 1915, and it was immediately acclaimed by historians as, “admirably edited.” The footnotes are a Freeman hallmark. Freeman adored scholarly apparatus. There are times in Freeman’s text, especially in Robert E. Lee, where you have three lines of text and the rest of the page is an explanatory footnote or footnotes. I mean, he was absolutely crazy about footnotes. “George Washington was the first U.S. President. Footnote one.” But they’re not just the sources. They’re explanatory. There’s meat in the footnotes that Freeman writes, and this is especially true of Lee’s Dispatches. He would write a footnote about a particular general, and he’d say, “This person graduated, was born here, graduated West Point in such-and-such a year, command this unit here, etc.,” and it gives some meat to the story so that the reader can know what’s going on. One of the reviews of the book said: “It is not at all necessary to refer to other works for a full understanding because of the quality of the footnotes.” This success led to Freeman’s greater work in R. E. Lee: A Biography. Scribner’s publication house had noticed this young scholar and in November 1915 they asked him to write a one-volume bio of Robert E. Lee, which was originally scheduled to be around 80,000 words. Freeman started doing his research in heretofore untapped sources. He would do things like go to West Point and look at the books that were checked out of the library by Cadet Lee, look at what books were in the library when Lee came back as the superintendent, things that had not been done in previous biographies of General Lee. He was really successful in digging up new stuff on General Lee’s life before and after the war. The major failure he ran across was getting access to a group of letters from Lee to his brother Charles. These letters were held by a Mary Custis Lee DeButts. Miss DeButts refused all of Freeman’s entreaties to be allowed to see the letters. Since that writing, Elizabeth Brown Pryor has written a book called Reading The Man, which is another publication of a series of letters by Lee. She was given access to see (I think) all of the letters from listening to her interview. But Ms. Pryor was not allowed to publish the contents of all that. Some of them are kind of salacious, so Miss DeButts’ descendants have refused the right to publish those as well.

Once started, however, Freeman kept going deeper and deeper into primary sources. He actually outlasted his first publisher, who died in 1923. This guy had been writing Freeman, “Hey, where’s the book? Where’s the book? Where’s the book?” And finally, the poor guy died eight years into the project. The guy, you know, is no longer there. And he gets a letter from Scribner saying, “Hey, you know, your editor is now dead. What’s the story in the book?” Freeman wrote the guy and said, “Look, I really would like to have a definitive biography of Robert E. Lee. There have been other bios of Lee, but I want to make this one the bio of Lee.” So, he laid out what he’d been doing and where he intended to go with it. And the new publisher said, “Okay, we’re going to give you the go ahead, take as long as it takes to write it. We want you to write a ‘really large and definitive life of Lee.’” So, Freeman did that. He published volumes one and two in October 1934 and volumes three and four in April 1935. The reviews from authors as disparate as Stephen Vincent Benét and Dumas Malone were extremely favourable, and the work was awarded the 1935 Pulitzer Prize for Biography, Freeman’s first of two. After the publication of R.E. Lee, Freeman cast about for his next project. What he wanted to do next was a definitive biography of George Washington, another Virginian and military figure. Freeman got started, but he found pretty quickly his heart wasn’t in it. He wasn’t as passionate writing about Washington as he had been about Lee, and his wife Inez explained to him why. She was able to diagnose her husband. She told him: “You have kept General Lee’s company daily for thirty years. You miss his peerless companionship.” So, in June of 1935, Freeman contacted his publisher and suggested he write a collect a collective biography of Lee’s subordinates. Now, there had been capsule bios of general officers in the Confederate service before, but what Freeman wanted to do was one continuous narrative in which actors would come onto the stage, play their roles, and depart. To give some examples. John Bankhead Magruder, who you maybe never heard of, appears in volume one. He pretty quickly is promoted, promoted to service in Texas, which is where all not-so-good officers went. He’s gone by volume two. John B. Gordon from Georgia starts out as a captain in volume one. By the end of volume three, he’s a major-general and corps commander. So, this was one continuous narrative, and the result was Lee’s Lieutenants.

Lee’s Lieutenants was published in 1942, 1943 and 1944, and Freeman himself had said that he had a didactic purpose in mind while writing this. He had something to teach, and specifically he wanted to help American commanders and staff officers understand something about warfare. He wanted to write about what we now call command climate, where, you know, the way that an officer conducts himself has a profound influence on the way the unit organizes. If you ever have had a boss where if you bring him or her bad news and she says, “Dadgum it, I’m so pissed off at you for bringing me this bad news,” then that says something about the way that the organization is going to run and people will learn to hide bad news. That has an impact on how the organization runs, and if you bring a person bad news and they react with magnanimity and equipoise, then that says something else about it. What Freeman wanted to do was to teach how to organize and lead an army effectively. This is a period when the U.S. Army was growing massively. Our army was, I think, something like 121,000 soldiers in 1940. In 1945 we had 12.8 million men and women in uniform. So, there was some learning to be done by people that were promoted in rank. Of all the books that Freeman wrote, he said that this was his best work. He didn’t win a Pulitzer for it, but I would tend to agree. I recommend it highly. Lee’s Lieutenants is wonderful history. It captures events in Virginia from Manassas to Appomattox with skill and insight. Freeman had finally accomplished his promised and self-appointed task of telling the story of Confederate soldiers.

Once his task was accomplished, Freeman devoted himself unreservedly to the writing of his bio of George Washington. The contrast between Washington’s story and that of the Confederacy is stark, however, as you can imagine. In Confederate history, you always had a pervasive sense of tragedy, I would say Greek tragedy, that people there knew they had roles to play, that the outcome was inevitable, but they still had to play their roles. In Washington there was always a story of hope. Washington might lose a battle, but everyone knew how the story was going to end, that the Washington would win the war. Even as the characters in this story of Washington’s biography grow old, the republic at the end of the story is still young. So, there’s a total change of mindset between the two books. Freeman started his biography of Washington, and finished it on the late morning of June 13th, 1953. He completed the final sentence of volume six, he went and had lunch with Inez downstairs. He went back up to his study and had a massive heart attack and he died in his house at 4:20 P.M. He’s buried in Hollywood Cemetery, not far from John Randolph, Jefferson Davis, and George Pickett. Freeman’s research assistants completed volume seven of the work the next year, and the bio was awarded his second Pulitzer Prize, this one posthumous.

Now we turn to some of the characteristics of man, his views on religion, life, race, politics, and the like. Freeman was a lifelong Baptist. Early in his adult life he had considered a life in the ministry. As a young adult, he served in the mission in downtown Richmond, where he met his future wife, Inez. He started each day with prayer. He devoted himself to service both in the church and in secular things; there was a religious motivation to what he did. He said: “A man never wastes time or money he gives to God, for the very exercise of self-control, and by the very sacrifices he makes, he becomes the more capable.” Freeman believed there were four treasures in a man’s heart: His reading, his prayer, his experience, and his service. Freeman served on numerous public benevolent boards and organizations. He spoke of the requests at venues as far away as New York and Montevallo, Alabama. His rules for speaking were these: “Have something to say, know your audience, have self-confidence, and develop a proper speaking voice.” He was a member of the Board of Trustees at the University of Richmond. He resigned in 1950 after a forty-year connection with that institution because the University of Richmond had offered an athletic scholarship to a football player. He was completely opposed. He would probably be appalled by what goes on today in college athletics. He was not opposed to physical education, but he thought the scholarship was a dangerous and backward step. He did not understand how “every college could have a winning team and nobody have a losing team.” And he said, you know, basically every Saturday, half the teams lose. So why would you want to invest money in something like that? In July of 1914, he was named associate editor of the Richmond News Leader, an afternoon paper. In an editorial commemorating the burning of Richmond, Freeman wrote: “We built on valour, not on ruins. There were traitors to meet, enemies among us. There was want and privation and hunger and night. We had met them in the trenches and still we had lived. The enemy could overthrow our government, but never a people.” The next week, speaking on the anniversary of Lee’s surrender, Freeman wrote this in the editorial page: “Virginia does not say that Appomattox was for the best. She can only say that she has made the best of Appomattox. “Freeman realized that his tastes were somewhat more elevated than those of his readers. Still, he tried to raise the intellectual level of his readers. For example, the announcement of the armistice in 1918 brought 66,000 purchasers to the News Leader. A salacious murder case in Richmond brought 72,000 purchasers to the News Leader. He was a little bit disappointed in how people responded to important things versus salacious things.

Freeman had some interesting views on race. He’s obviously a product of the Progressive Era. He attacked the system that allowed a minor black man to plead guilty to murder without benefit of counsel. There was a murder in, I think it was Amherst County, that this young black man who was a minor was accused of, and he pled guilty to murder, knowing he was going to be executed, and he had he never had benefit of counsel. Freeman took on the judge and said he had committed an injustice by letting a minor plead guilty to murder knowing that the penalty is going to be death without letting that young man talk to a lawyer. The judge did not appreciate this editor from a Richmond paper taking him to task, but in the end, Virginia corrected the error. They rescinded the guilty plea and allowed the young man to talk to an attorney. Freeman also looked forward to, “that grand day when there is no colour line in the newspapers.” Like many white Southerners, however, Freeman was not ready to support black voting. Virginia had changed the Constitution in 1903 to disfranchise African-Americans, and he supported that policy. He accepted poll taxes as a means of disfranchisement, saying this in the editorial page: “Shall we extend the franchise in Virginia by abolishing the prepayment of poll taxes as a prerequisite for voting? No, a thousand times no. Interest and participation in government are today desirable only when they are intelligent and well-informed.” Well, we might look at the current mess we’re in and say that might be not a bad policy. I’m not sure that the poll taxes are the right way to go about it, but there you go. At the same time, he was also working for the day when African-American Virginians would, in fact, get the franchise. He wanted them to qualify themselves to vote. He wasn’t in favour of just giving it to them. As a Southern Democrat, Freeman was fawning in his praise of Woodrow Wilson, the sorriest of the Virginia presidents. Freeman was a lifelong Democrat, and I think that was a result of his father’s experience in the War and Reconstruction. Freeman beat the drum for war in 1915 to 1916, something that he later regretted. He admitted in an interview later on: “I was groping blindly while cheering loudly. I knew not what I did.” The bottom line is he learned. On the other hand, Virginius Dabney of the Richmond Times-Dispatch said of Freeman that he was: “An inveterate foe of the meddlesome cleric and the pseudo-statesman.” Few editors in the South, Dabney wrote, were, “so consistent in the championship of the Negro or belabour the Patrioteers and the industrial Bourbons with equal regularity. Freeman initially supported Franklin Delano Roosevelt, but when the New Deal program was unveiled, Freeman, ever a fiscal conservative, grew increasingly leery. In his diary he worried about the destruction of the British and French social order in 1939, but he refused to rush into war again. He wrote: “Thank God for the Atlantic Ocean.” In his paper, he wrote: “Stampede and hasty action are to be avoided at any price.” In a 1940 letter to the owner of the News Leader Freeman wrote: “I am determined not to permit propaganda, emotion, hate, short-sighted argument, and misbranded patriotism to bring me again to the psychosis of war I shared with millions of stampeded Americans. I have to live with my mind and my conscience after the war.” So, at the beginning of World War Two, he was a very reluctant combatant. This consideration guided Freeman’s editorial slant in the run up to World War Two. He expressed, “a detestation of everything, save, discipline for which the Nazis stood.” The memory of, “the World War and its dislocation of national life, of all the inflamed hatreds, of all the spiritual losses that attended our participation in that overseas war,” and a deep knowledge of military history informed Freeman as he wrote his editorial page. Freeman would not have it otherwise: “I unhappily know too much of war to be certain about anything of war, except that it is uncertain. Behind the most blaring confident trumpets today may be more of wind than of wisdom.”

When the final volume of R.E. Lee was published in 1935, Freeman was awarded the Pulitzer, as I said earlier, and accepted. And he may be speaking perhaps to us as much today as he was to people of his day. In his acceptance speech, he declared:

“I shall be very happy if, in this day of false fear, doubtful counsel, and whining attempts to escape the consequences of our own acts, this award brings again to public emulation a man who embodied courage, decision, and a willingness to pay the price of loyalty to his convictions.”

Pretty relevant stuff today, I should think. In 1940, when it appeared FDR might not seek a third term, Freeman sat down and wrote an article to FDR’s successor, whoever that might be, outlining what he thought were the proper role of a war president was. First, a president ought to define the war aims, Freeman said. Then the president ought to, “muster in support of them the national resources. The president should insist that the larger strategy of military and naval operations conform to the war aims.” Then the president should, “select the best men he can find to execute a sound strategic plan.” Finally, the president should support his generals and admirals and sustain the morale of the nation. That’s pretty good advice. Freeman came to respect FDR’s war leadership, even though he was not a New Dealer, and he grew to admire the military leadership of general officers like Marshall, Eisenhower, and MacArthur, with each of whom he exchanged letters. He was an important enough military writer that these guys were writing him in the lead up to and during WWII. MacArthur, for example, wrote to Freeman: “I have studied Lee and Jackson, and it seemed to me almost that these chieftains in gray were there to comfort and sustain me.” When FDR finally died, Freeman had high hopes for Truman, which were quickly dashed. Truman and the men around him were “mediocre.” In Freeman’s judgment, their “lack of leadership” rivaled their “lack of courage” as their defining characteristic. A staunch fiscal conservative, Freeman opposed the Greek relief bill and the Marshall Plan. He warned, “America will bankrupt herself in trying to save bankrupts.” Those in office, it seemed, “never had any conception of what it represented in blood and sweat by the taxpayers of the country.”

Freeman finally lived in the Virginia of the Byrd machine, which was a political machine of some power, and with which (or, more accurately, around which) he played ball. He was able to operate in Virginia in the era of the Byrd machine without ever running afoul of it, which was no mean feat. He didn’t really support him. He was not a Byrd man. But he didn’t run afoul of him either. He was always suspicious of extremes. As for the cause of the war for Southern independence, Freeman said this:

“The War Between the States had its origin between the new ideals and old. It was fundamentally a struggle between the rural society of the old colonies and an urban society of New England, which had the full support of the white new states of the Middle West. New England wanted a protective tariff and the South did not. When protectionist New England and the states of the Middle West combined, there was a clash inevitably with the conservative rural South. Slavery was a factor and an important one, but the slavery issue was exaggerated by the politicians. If you said to me, ‘state the cause of the War in one word,’ I would protest that this could not be done, and then I would say that the word which more nearly covers everything is the one word, ‘politicians.’”

Okay, let’s talk about Freeman’s merits and some of his innovations, his philosophy, his history. He believed that the historian was to be an expert scholar working according to defined principles and pursuing his experiment, just as does the investigator in the scientific laboratory. That is a product of turn of-the-century ideas about what the craft of a historian is. First off, you’ve got to know your material. You’ve got to run your hands through the soil of the period you’re writing about so you can become familiar with what it is. He said: “Nothing could be more delightful than the hope and the outlook of a calm study of the events and men, which in turn, in time, have made the world what it is.” Freeman was absolutely meticulous in his research and writing. There was nothing in the biography of Robert E. Lee, he said, that could not be documented. If he said that Major Jones, who rode up to Lee on the afternoon of September 17th, 1862, had a mud-splattered uniform, it was true because he had found a source to document that. He wrote the Italian Embassy for the meanings of Italian words. He wrote to the curator of Mount Vernon to ask what the son was doing on the house at the afternoon at this particular time on this date. He would go to that kind of expense of time to document what he was saying. Freeman wrote about what he thought was important in writing history. Here’s bit of advice might be useful in some of today’s academic climate: “Moderation of statement and recognition of the honesty of opposing points of view are among the most important things that I know,” as opposed to ax-grinding, which happens in some cases today. Freeman strove for “complete intellectual humility.” He also strove for simplicity of style: “Too many good ideas are ruined by being overdressed, much as many women are.” He did pioneer what’s called the fog-of-war technique. Now, generally narrative histories of this period had been written from the God’s-eye-view, where you get to see everything as it happened and related as if everyone knew everything about everybody. Freeman did not want to do that. He wanted to write his history from the perspective of what General Lee knew at the time he knew it. Only that way can you honestly and fairly evaluate the decisions that Lee made. That was an innovation, and an important one, I think. Freeman sought to, “maintain a single point of view and describe that battle on a basis of what Lee knew rather than on the basis of what we now know.” To avoid bogging down the narrative, he included voluminous explanatory footnotes, which is, I think, the reason why there are so many and such huge footnotes in his works. Because if you want to see, well, where did he get this or that idea, or who is this person he’s talking about? You can go to the footnotes and there are always footnotes, not endnotes. They’re at the bottom of the page. You can you can see them, but you don’t have to read them, which is great because it keeps the flow of the narrative going. Freeman also wrote appendices which are which are excellent as well. Lee’s perspective of things as he knew them at the time was critical to analyzing the performance of the man in his duty. So, he went for the same thing in Lee’s Lieutenants. He discusses what people knew at the time and evaluates their decisions based upon that perspective, which is important because otherwise, if you have the God’s-eye-view, then it’s not fair to the actors at the time to say, “Well, this guy made this decision, that was a bad call.”

Okay, work hours. This is something that’s just unbelievable about Freeman. He said: “Work is the greatest satisfaction I know. Talk about delights, but to my mind there is no delight commensurate with that of a good day’s work and a long one, and an humble art and a strong one.” Freeman would rise at 2:30 in the morning. Yeah, 2:30. I’m an early riser, but that’s early even for me. He would say his morning prayers. He would leave arrive at the newspaper at 3:10. En route he would drive down Monument Avenue and he always saluted the statue of General Lee. One day he was so involved in thought that he forgot to salute Lee, so he turned his car around and drove back to the Lee circle and saluted the general before he went to work. At 3:25 he would be at his desk, and he would read the Richmond Times Dispatch, which was the morning paper. The first issue of the morning paper would be out by that time, and he would read what his competitors were doing. At 8:00, he would have an AM radio broadcast. He’d go to the radio station next door to the newspaper for the day’s first radio broadcast. He did two radio broadcasts a day and would just talk about whatever he thought was important. It could be history, it could be life, it could be gardening. But for a long time, he was on the radio. Returning to the News Leader, he would hold a staff meeting, write his daily editorial, and then have another radio broadcast at Noon. Then he would go home. So, he’s done. His work day’s done at Noon because it started at 3:25. He would have lunch, he would speak with his wife, Inez, and sometimes engage in gardening. He would go upstairs to his third-floor study at 2:30 P.M. for a quick nap, probably half-an-hour. Then he would spend the balance of the afternoon writing whatever work he was working on, whether it was R.E. Lee, Lee’s Lieutenants, or George Washington, until 6:30, when he came back downstairs and had supper with his family and entertained guests or spent the evening en famille. Finally, he’d go to bed at 8:30. So, he ran on six hours of sleep a night for decades. Freeman had an incredible work ethic.

I think Freeman was a brilliant stylist. I’m going to read a couple of quotes in extenso so you can judge for yourself. First is one from R.E. Lee. Freeman’s talking about the human wreckage on the morning after the disastrous battle of Malvern Hill, which occurred on July 1st, 1862, the last battle of the Seven Days, so he’s describing the morning of July 2nd. This disastrous charge has happened and been beaten back handily by the Union forces. The Confederate infantry made several disjointed and uncoordinated charges. It was a comedy of errors, it just was a disaster, a tragedy:

“A heavy mist as wet as rain hung over the battlefield when July 2 dawned. From the Confederate side it was impossible to tell whether the enemy still held Malvern Hill or had retired. Lee’s brigades were still hopelessly confused. Commanders did not know where their men were; men could not find their officers. As it grew lighter, three thin regiments of Early’s brigade were visible near the centre in the open field. To their right lay not more than a dozen weary men, Armistead among them. A little farther around the Crew house hill, with their faces still toward the enemy, were the remnants of Wright’s and Mahone’s brigades, stoutly holding the ground they had won under the muzzles of the Federal guns. Elsewhere, over the field of the charge, only the victims of the slaughter were to be seen amid the debris of the battle. ‘A third of them were dead,’ attested a Federal officer who stood not far away, ‘but enough were alive and moving to give the field a singular crawling effect. The different stages of the ebbing tide are often marked by the lines of flotsam and jetsam left along the seashore. So here could be seen three distinct lines . . . marking the last front of three Confederate charges of the night before.’

On the crest of the hill a mixed Federal force of cavalry and infantry was waiting. It made a show of advance, but drew back at the first fire of scattered Confederates. A few score of Huger’s men came up about this time and at Early’s instance reported to Armistead. From the woods the ambulance details began to trickle slowly out; officers rode forward; soon an informal truce prevailed and thousands of hungry, restless men emerged from the woods to search for missing comrades or to look for food in the haversacks of the fallen. Shattered bodies were everywhere and dead men in every contortion of their last agony. Weapons and the keepsakes of soldiers, caps and knapsacks, playing-cards and pocket testaments, bloody heads with bulging eyes, booted legs, severed arms with hands gripped tight, torsos with the limbs blown away, gray coats dyed black with boys’ blood — it was a nightmare of hell, set on a firm, green field of reality, under a workaday, leaden, summer sky, a scene to sicken the simple, home-loving soldiers who had to fight the war while the politicians responsible for bringing a nation to madness stood in the streets of safe cities and mouthed wrathful platitudes about constitutional rights.”[2]

In a speech Freeman gave at the dedication of the Lee statue in the Virginia capital, he said this of the man whose biography had engulfed nineteen years of his life:

“Character is invincible. That, it seems to me, is the life of Robert E. Lee in three words. No three words could convey a message more needed in this dark crossing of the Valley of the Depression, in the management of the Arlington Estate, in the Organization of Virginia Forces, and the long campaigns of his army, and in his labours as a college president, General Lee had hundreds of practical questions he could not solve by any fixed process of reasoning. But I think I can say that he never faced an ethical question that he did and did not answer quickly by the clear mandate of a conscience that recognized no grays, but only blacks and whites, right and wrong. It was because he heeded that mandate through life that he did not hesitate in the last hour when hot blooded youth cried out, ‘Oh, General, what will history say of the surrender of this army in the field?’ Lee responded, ‘I know they will say hard things of us: They will not understand how we were overwhelmed by numbers. But that is not the question, Colonel: The question is, is it right to surrender this army. If it is right, then I will take all the responsibility.’ [3] God Grant those words of invincible character will echo through this America today and will silence the voices that cry: ‘The question is not is it right, but is it expedient? If it is not expedient, I disclaim all responsibility.’ Whether there be statistical prophecies, they may fail, whether there be smooth tongues they may cease, whether there be superficial knowledge, it may vanish away. But character, like charity, never faileth. For the solution to our nation’s problems today, character is as much needed as logic.”[4]

There were a number of Confederate Veterans’ parades in Richmond and Freeman always noted them in the editorial pages of the News Leader. They announced in 1951 that the upcoming parade would be the last one because the veterans were too old to have another. In an article entitled “The Last Parade,” Freeman wrote:

“They thronged the streets in this old town when Bonham brought his volunteers and their Palmetto Flag in 1861. They cheered the lads who took up arms when Virginia called. With doubtful glance they looked upon the men who hailed from New Orleans, the Tigers of the Bayou State. When Longstreet led his veterans from Centerville to hold the Yorktown line, all Richmond brought out food and flowers and draped the bayonets. When first the city heard the distant growl of Union guns, each regiment that came to strengthen Lee was welcomed as the saviour of the South. The long procession of carts that brought a groaning load across the Chickahominy from Gaines’s Mill was watched with aching hearts. Another year and solemn strains and mourning drums received the train that had the silent form of him who was the right arm of his famous chief. That was the darkest day, save one, that Richmond ever knew. For when Stonewall fell, the stoutest bulwark of the South was down. With Jackson dead, was there another such? When Pickett’s soldiers came, a shattered fragment of defiant wrath, to tell how hell itself had opened on that hill at Gettysburg, the townsfolk gazed as if on men who had upturned their graves. The months that followed saw a steady flow into the mills of death. Each night, the sleeping street was awakened by the tread of veterans who hurried on to meet the sullen Meade or hastened back to check the wily Sheridan. The clatter of horses’ hooves, the rumble of the trains, the drum at dawn, the bugle on the night air. All these the leaguered city heard till children’s talk was all of arms, and every chat across the garden wall was punctuated by the sound of fratricidal strife. Ten months of thunder and ceaseless march, and then the end. Brave Custis Lee led out the last defenders of the town. Limping Ewell rode away while flames leaped up and bridges burned and Trojan women waited death.

The next parade was set the fastest time as up the hill and past St. Paul’s and in the gates the federals rode and tore with wildest cheers the still-defiant flag from off the capital. Dark orgy in the underworld and brutish plunder of the stores. A wider stretch of fire. The mad rejoicing of the slaves. The sly emergence of the spies. And after, the slow return of one great rider through the wreck of flames and dreams, a solitary horseman on a weary steed with only youth and age to pay him homage as he stopped before his door, bowed to all, and climbed the steps and went within and put aside his blade to work for peace. Excited days of preparation then, and pontoons thrown across to James. The army of the victor Grant, the gossip said, was soon to march through Richmond and see the ashes of the pinnacles on which its distant gaze had long been fixed. They came in endless lines. All day they moved, all night, until the city’s tearful folk became bewildered in their count and asked, ‘How could the thin gray line have stood so long against that host?’ At last the blue coats left and civil rule returned in poverty and pain, but with a memory that made the humblest rich. The fallen walls were raised again. The peaceful smoke of busy trade rose where the battle fumes had hung. For twenty years the soldiers of the South remained behind the counter or the plow until the day when Johnston led them out to lay the cornerstone of what the South designed to be a fit memorial to the matchless Lee. A few years more and when the figure stood upon the pedestal, the word ran out that every man who had worn the gray should muster in ranks again and pass before the chieftain on old Traveller.

A day that was when love became the meat of life. Reunions multiplied. A grateful city gladly threw its portals wide each time the aged survivors of Homeric strife returned to view the scenes of youth. A deep emotion rose as Forrest’s troopers galloped past and Texans raised the rebel yell. Today, the city has its last review. The armies of the South will march our streets no more. It is the rear guard engaged with death that passes now. Who that remembers other days can face that truth and still withhold his tears? The dreams of youth have faded in the twilight of the years. The deeds that shook a continent belong to history. Farewell! Sound taps. And then a generation must face its battles in its turn, forever heartened by that heritage.”

Okay, critiques. I’ll say this about Freeman. First and foremost, he was a Virginian, and that’s both his strength and his weakness. He was almost fawning in his praise of Woodrow Wilson, although mercifully he lived long enough to correct that. Like Lee, Freeman suffered from geographical myopia. He focused on Virginia to the almost total exclusion of other theatres of the War for Southern Independence. One could argue (many have) that the War was won in the Western Theatre. This, however, is a critique based on the assumption of Northern victory. I can only say that in my military opinion, if the South was to have won that war, it was going to win it in the Eastern Theatre where the South had put his greatest generals and its best army. A nation cannot win by covering its weaknesses. It wins by exploiting its strength, and Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia were obviously the Confederacy’s strength. Freeman knew this, but his perspective today is labeled as a “Lost Cause” view. But he did focus on Virginia. R.E. Lee and Lee’s Lieutenants were almost exclusively about the Virginia theatre. One could accuse Douglas Southall Freeman of being overly harsh on Longstreet. In R.E. Lee, Douglas Southall Freeman is sharply critical of Longstreet. In Lee’s Lieutenants, Freeman toned down that criticism a bit, but in both works Longstreet comes across looking self-righteous, insubordinate, petulant, and willfully disobedient. I say this as a descendant of one of Longstreet’s veterans. Perhaps this is unfair, especially in light of the fact that Lee called Longstreet “my old warhorse.” Freeman believed that Lee saw his job as bringing the troops to the battlefield and letting his generals conduct the battle. I’m not sure this is an accurate assessment. Lee’s performance at Chancellorsville gives the best counterargument. Lee’s conduct on May 1st, May 3rd, and May 4th showed “Marse Robert” was not a hands-off commanding general. He was intimately involved in the details of Sharpsburg, Spotsylvania Courthouse, Newmarket Heights, and the sad retreat to Appomattox. Sometimes Lee was badly served by his subordinates, but he was not detached. But Freeman says over and over in his bio that he believes Lee believed his job was to get forces to the battlefield and let his subordinates take over.

Freeman’s biggest failing (and he would probably agree) was as a father. He had three children, two girls and a boy. The girls came out fine and lived a long and happy life; I think the eldest is still alive. In his son’s case, though, the story is much different. Freeman’s son did not have his father’s work ethic. He joined the Navy and then was dismissed from the Navy. He got married and then divorced. He became an alcoholic and had a very, very difficult time figuring out what he wanted to be and what he wanted to do with his life. Freeman was chagrined by this his entire life. In an interview for the bio of Freeman, this man said: “My father was never present,” and I think Freeman lived to regret that. So, the flip side of Dr. Freeman’s remarkable work ethic was his relative absence in his son’s life. He wasn’t there to help mold the character of what was, he would probably say, his most important work – his son. On the plus side of the equation, Freeman’s works are still the definitive work on Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. If anyone wants to know where Lee was at any particular point in time between 1861 and 1865, what Lee was doing or thinking, then Douglas Southall Freeman’s bio of Lee is the place to start. His analysis of military operations was excellent, and he wrote extensively in editorial pages about World War One, the War for Southern Independence, the American Revolution, and World War Two. His judgment was so sound and his knowledge so broad that presidents and generals often consulted his opinion. Even though he had never put on a uniform in his life, any military analysis of those wars still needs to wrestle with the interpretations Freeman made.

Okay, significance. He won two Pulitzer Prizes. The list of people who can say that is pretty significant: Robert Frost, Norman Mailer, William Faulkner, Carl Sandburg, Robert Penn Warren. That’s some pretty good company to be in. Sadly, most of Freeman’s works are no longer in print. R.E. Lee, Lee’s Lieutenants, and George Washington have all been abridged by other authors.[5] I wouldn’t recommend reading the abridgments, however. Has anybody seen the Mel Brooks film where one of the characters talks about playing highlights from Hamlet?[6] That’s what I think an abridgment of Douglas Southall Freeman is like. I wouldn’t recommend it. Otherwise, Freeman’s work has largely been consigned to the secondary market. If you’re on a limited budget and you’re looking for R.E. Lee: A Biography, there is this really bizarre Frenchman named Thayer, who has sat down and typed out the entire work and put it online so you can read it with the footnotes inserted into the text. And thank God that he has. Even if you have the money to buy hard copies, Thayer’s digital edition is still immensely useful for research and as a reference work. Fortunately, Freeman’s books have been digitized and can be accessed for free in their entirety via the relevant hyperlinks in paragraph two. You may need to create a free account with archive.org to access some of them.

When Freeman died, Jack Kilpatrick, one of Freeman’s subordinates at the News Leader, said this: “Those who knew The Doc and loved him for the essential humanness at the core of his genius have no adequate way of paying him tribute or expressing their sense of loss and sorrow at his death. There is a numbness now, left by shock and disbelief, and it will be a while before we realize how much was taken from us by his death.” If I can borrow a phrase from the Bard of Stratford-up-Avon, I would say this: “He was a man, take him for all in all, I shall not look upon his like again.”[7] In the end, Douglas Southall Freeman was the Southern historian’s historian. Thank you.

[1]The Confederate Memorial Literary Society later became the Museum of the Confederacy.

[2]R.E. Lee, Volume II, Ch. XVIII, 220-221. https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/People/Robert_E_Lee/FREREL/2/18*.html

[3]As Charles S. Venable, one of Lee’s staff officers, asked him on the morning of 9 April 1865. See Freeman, R.E. Lee, Volume VI, 121. https://archive.org/details/releebiographyby04free/page/120/mode/2up cf. Armistead L. Long, Memoirs of Robert E. Lee, 422. https://archive.org/details/memoirsofroberte0000long_g4t9/page/422/mode/2up

[4]Freeman clearly was referencing 1 Corinthians 13:8, probably the KJV. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=1+Corinthians+13%3A8&version=KJV

[5]Richard Harwell abridged R.E. Lee and George Washington. Stephen W. Sears abridged Lee’s Lieutenants (and later modeled a study of the Army of the Potomac after it).

[6]To Be or Not To Be, 1983. The film starred Brooks and his wife, Anne Bancroft, and was itself a spoof of Ernst Lubitsch’s 1942 classic of the same name starring Carole Lombard and Jack Benny.

[7]Hamlet, Act I, scene II. https://shakespeare.folger.edu/shakespeares-works/hamlet/act-1-scene-2/

This was a great synopsis of Freeman’s life and works. Very well done. Thanks for publishing it.

I really enjoyed this. I wish the hard copies of Freeman’s unabridged works were still in print.