A Review of My Silk Purse and Yours: The Publishing Scene and American Literary Art by George Garrett, University of Missouri Press, 1992

My Silk Purse is a collection of 36 of George Garrett’s essays and reviews, largely on the American publishing and literary scene. The essays are rather tightly a unit, having an underlying philosophy which provides the measure by which Garrett views and judges. And judge he does. All is not relative, for Garrett. There are certain unchanging values and principles by which to gauge whether we measure up or not. These he often calls “the Old Verities,” probably borrowing the phrase from Faulkner’s Nobel speech; and they are derived, as his allusions show us, from King James Scripture, the Book of Common Prayer, Greek and Latin classics, Augustine, Chaucer, Caedom, the English Elizabethans, and a very wide and catholic range of reading besides.

Garrett is without doubt one of the best read critics of our time— well-read in both the writing of our own day and of centuries past.

He has a mind free to see through the cons of our age, and is discerning of what is true and genuine as opposed to what is not. His title suggests the same. “My silk purse” means “things of value and of genuine worth,” in contrast to the proverbial opposite, the “sow’s ear” that con artists would like to pass off in substitution for the former. In our time, the sow’s ear has been swapped for the silk purse; and chaos, confusion and absurdity have been the result of the cheat. “Society cons with selling us a sow’s ear and letting us think it is a genuine silk purse,” Garrett says in his essay “Making it”; and hence his title.

So his book will be about distinguishing what is valuable from what pretends to be; and his silk purse here contains essays better than coins. Garrett sees that the American publishing scene and literature are indicative of the entire Establishment Society. Therefore, this volume is of far wider interest than strictly literary. His critique of the day is Swiftian in its comprehensive, relentless satire of the absurdity of elitist-intellectual America in the last decade: its media, literature, publishing, social sciences, religion, and politics. Garrett sees through the fogs of social and political dissembling—the mindless fashions that have hardened into cliches that may have once been harmless enough, but that now threaten to tyrannize—that have made us intellectually brain-dead. Things have gotten very bad, indeed, writes Garrett:

[It] is now widely accepted and understood that evidence which weighs against fashionable contemporary political and social positions is to be suppressed, or at least modified and limited so as not to offer any ammunition to the skeptical opposition. I can recall that once upon a time we laughed at science under Stalin, never dreaming that most of its practices, if not all of its excesses, would come to pass here. . . I have only recently returned to the twentieth century from a couple of decades spent living as an expatriate, an alien, in the sixteenth century. And it is my best and considered judgment that then and there, in Tudor England, when the consequences—and legal consequences—of asking certain questions, voiced opinions, even (at times) thoughts and intentions, were deadly serious, there was probably more honest, deep digging, and far-reaching debate and dissent than we have experienced in this free society for more than a quarter of a century. Even under the rigors of almost absolute monarchy they were not afraid to debate not only current issues but also, maybe more important, first principles.

Garrett’s is a book that addresses “first principles.” There is open dissent from the prevailing fashions in his pages; and it is done with great wit and style that, in his own accurate words, is “brash and sassy and full of bile and irony.” Garrett sees himself as a kind of good-natured revolutionary, using words rather than bullets. (He paraphrases Nobel laureate poet Czeslaw Milosz’s statement that telling the truth is like firing a revolver in a crowded room). He often uses imagery of revolution and of doing battle with the follies, vices and scams of the time. His yardstick of “Old Verities” measures the hollowness and absurdity of the secular humanistic plan for the planet. Very refreshing is his healthy irreverence for the things that the secular society holds sacred. His well-phrased sentences are quotable: New York is “Babylon suffering under the delusion of being the New Jerusalem.”— “You never can tell about publishers. Here today and merged with Dow Chemical tomorrow.” — “Some prefer to escape the problems of the present by blaming them on the past (thus sharing their problems with the dead, practicing, as it were, intellectual necrophilia.)” —”The [genuine] writer is, in the simple and irrefutable medieval sense, a widow to this world, a contemplative.” —”In my Episcopal Church even the hard sayings of Jesus Christ have been put on the back burner, if not actually banned.”—The method and purpose of the American press is an “unceasing barrage of cliches. . . misinformation and disinformation and outright lies” “We are these days so concerned about monitoring our thoughts, even as we permit ourselves the crudest possible luxury and license by using the worst words our language allows.”—”If you listen at all to what might accurately be called Radio Daniel Schorr, I mean National Public Radio, you know that the flute and the acoustic guitar are the instruments of compassion and that compassion is a virtue exclusively reserved for the left and especially for those who must publicly assert that they have compassion.”—”It is hard to imagine any social unit as riddled with corruption as the American literary scene. . .Next to the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, the Court of the Emperor Caligula would look like an early session of the Council of Trent.”

Garrett’s catch phrases describing our times show how he feels our era measures up in the broad context of history. He continues:

This society that greatly rewards such things as an ability at slam dunking, a talent at posing in a bikini, or singing (well or badly, on matter) the twenty-five words or less that, according to Iggy Pop, constitute the entire vocabulary of rock and roll. . .And this is an age and society which join to offer equal recognition to Nobel Prize winners and to naughty politicians, preachers and casual girlfriends or boyfriends as the case may be. A society in which fame and notoriety are, very often, exactly one and the same.

Indeed, this volume is far more than a limited look at American publishing and the literary scene, which, wisely, are not taken out of their social context. Again, as Garrett shows, they can’t be separated, because they are one and the same.

Of American publishing itself, Garrett’s ire is directed most closely on the New York Establishment’s “Star System.” Garrett writes that the American publishing scene’s great corruption (which includes the sacred cow New Yorker magazine) has been “the attempt to create (by fiat as much as fact) its own gallery of stars,” and to keep them in that galaxy by marketing, hype and promotion. The Manhattan establishment “takes very good care of its own” and of its literary reputations. This they learned from the New England literati of the last century: “The New England crown was the literary establishment in its day. Uncontested, it seemed, certainly unchallenged since they had succeeded in destroying the South.” This has been the traditional way of American publishing; only now it is the New York gang and “Poetry Mafia” that have called the recent shots. Garrett is highly critical of the self-promoting, self-marketing “Star System” that denies the many humble, “genuine writers, not deemed ‘Stars’ by the Establishment,” but “who still survive the school of hard knocks and the great shrugs of indifference, even rejection.” Garrett’s essays on Southern authors Fred Chappell, Shelby Foote, R.H.W. Dillard, Madison Smartt Bell, Reynolds Price, among others, pay them tributes they are not likely to receive by the limousine liberal elite. His praise for the underappreciated “silk purse” writers who haven’t played the literary game of making it, and his naming those “sow’s ears” ones that have been undeservedly successful at it, run as a key unifying thread throughout the book.

Garrett is directly on target in describing Fred Chappell as “one of the best writers of my generation.” I personally would call him and Wendell Berry the best without qualification. Garrett writes, continuing his volume’s thematic thread:

Fred, by dint of hard labor and unmistakable achievement alone, without any boot or apple polishing, politicking or hustling or swaggering self-aggrandizing, has cracked the toughest and most defensive elite in the American literary scene—the Poetry Mafia. I am not fixing here to name any names. They are mostly Yankees and a very litigious crowd to boot.

Garrett is always certain to pay his respects to the writers of the past. His two essays on the Elizabethans, far from being off the subject, pay homage to the “Old Verities,” to establish something of what these truths have been, and to serve notice to the reader that he is not a brat author who thinks the world began only today. He sees that modern ignorance of the past and disdain for it, dangerously isolate a person in a vacuum and allow the modern marketing con artist to sell him the sow’s ear of shoddy thinking and writing. In our era, it is fame that is passed off for genuineness. And all with an insufferable smugness.

His calling a 1978 Solzhenitsyn talk “one of the great speeches of our age” provides a philosophical center for the book. Solzhenitsyn, like Garrett, attacks the spirit of American contemporary “liberalism” which stifles debate. Solzhenitsyn said:

Enormous freedom exists for the press [in the West], but not for the readership, because newspapers mostly give emphasis to those opinions that do not openly contradict their own and the general trend. Without any censorship, in the West, fashionable trends of thought are carefully separated from those that are not fashionable. Nothing is forbidden, but what is not fashionable will hardly ever find its way into periodicals or books or be heard in college.

So Garrett’s volume serves notice that it will dissent from the prevailing elitist intellectual attitude.

Garrett’s philosophical response to the modern scene, informed by a broad historical consciousness and an understanding of the “Old Verities,” tests the present against the past and finds the present lacking. Saying this to modern man is so very necessary if he is ever to grow wise. For the elite intellectual is not very wise at all, only something of a know-it-all, sitting high on his perch atop the apex of civilization, self-promoting, self-interested, like the Publishing Elite who help keep him on his perch. He may have facts, but little wisdom. Though he thinks, with his technology and scientific knowledge, that he stands at the pinnacle of advancement, he is the worse off for wisdom. He has forgotten certain essential truths that have always been counted the givens of wisdom, and the foundations on which to grow wiser. One is the inscription over the Oracle at Delphi: Gnothi Sautor, which our narcissistic era usually translates simplistically and wrongly: Know Thyself. The wisdom of Gnothi Sautor actually meant to the Greeks: Know your place before the Creator; know that you are finite; know that you are the creature, the created, not the creator. In other words, beware hubris. Hence, this business of man’s preempting the role of the Divine as the sole engineer of his own fate is truly the height of arrogance, not to mention a very foolish, rash and dangerous act. And this is the basic premise on which the new humanism is built, a humanism which is the religion of status-conscious academia and of the fashionable intellectuals that dominate the mind-control agencies of media and education. The Greeks knew that a knowledge of man’s finitude and limits (and that there should be limits of his desiring) was a beginning of wisdom. And this has been forgotten in the modern vacuum by our modern “wise” Elite. Garrett’s book is an open and effective assault on such modern smugness, complacency and arrogance, in an era diminished by these same fools in wise men’s places and their sow’s ears passed off as silk purses.

In closing, let me say that it seems that Garrett has become more radical over the decade. He quotes Jefferson:

God forbid we should ever be twenty years without a rebellion. . . What country ever existed a century and a half without rebellion? And what country can preserve its liberties if the rulers are not warned time to time that their people preserve the spirit of resistance? Let them take arms. . . What signify a few lives lost in a century or two? The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure.

Garrett comments:

[A] leader or statesman, from the citizens of the Greek city states, through every kind of emperor and monarch, absolute or benevolent, on through the rebellious generation of Jefferson, would surely and easily define our contemporary American social situation. . .tyrannical. And, as such, it would have always been deemed worthy of the strongest possible kind of resistance. . .Thus I can see that it can be decently and honorably maintained that certain complex and confusing issues troubling us in these times probably should have been settled in the streets, sealed in the blood of patriots and tyrants, rather than vaguely resolved in legislatures, courts or in the press.

Dangerous concepts? As dangerous as those on which America was founded because they are precisely the same. It is good to see that this, one of Garrett’s most recent essays, reveals that its author shows no sign of mellowing.

Garrett’s inspiration from Jefferson comes naturally from the Genius loci. When he walks to work at Cabell Hall, where he teaches at the University of Virginia, he passes beneath Jefferson’s words: “Here we are not afraid to follow Truth wherever it may lead nor to tolerate any error so long as reason is free to combat it.” If Jefferson can be pleased from his hillside at nearby Monticello, he must be so with My Silk Purse. It stirs the pot of inquiry and dissent in a reasonable way.

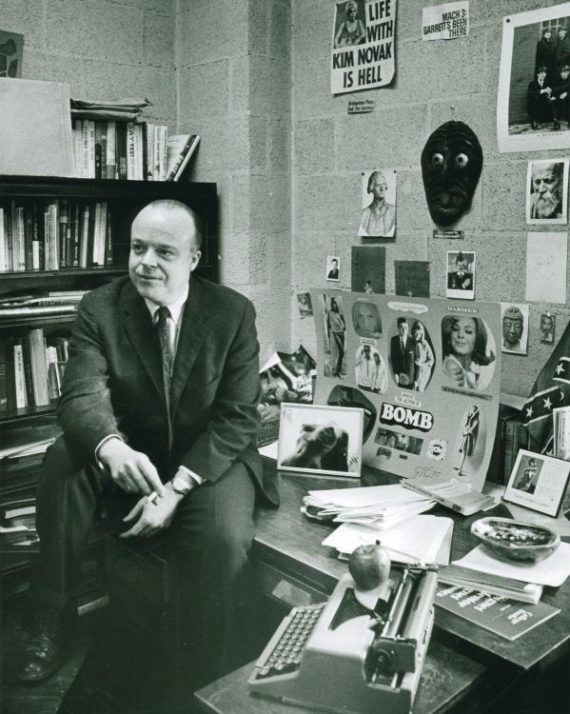

George Garrett is professor of creative writing at Virginia and describes himself as a Southerner “by blood and birth and choice.”