In 1994, The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography published Paul Finkelman’s “Thomas Jefferson and Slavery: The Myth Goes On.” It is an essay, cleverly crafted, which deserves critical examination, because, cleverly crafted, it overwhelmingly misleads.

Finkelman begins:

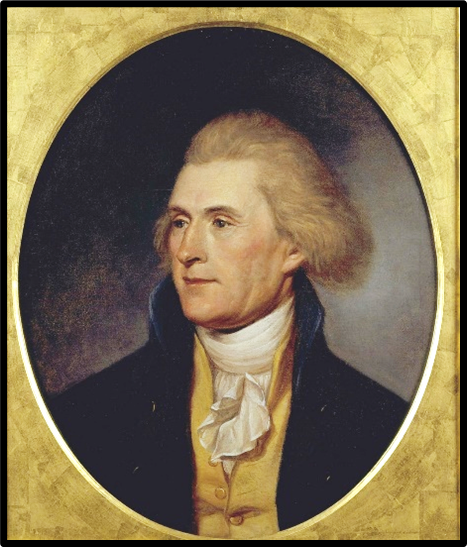

Thomas Jefferson is certainly the most popular saint of American civil religion. His closest rival is Abraham Lincoln. But Lincoln was merely our greatest president. He burst on the scene like a comet, saved the Union, ended slavery, and then was martyred. Jefferson was ever so much more: coauthor of the Declaration of Independence, president, father of the University of Virginia, philosopher, cofounder of the nation’s oldest political party, patron of the Lewis and Clark expedition, scientist, naturalist, spiritual godfather of religious liberty in Virginia, and the architect and owner of that great house full of furniture, art, scientific instruments, natural curiosities, gadgets, and other treasures that continue to fascinate Americans. The virtual deification of Jefferson is ingrained in the general public, sustained by popular biographers and scholars, supported by the mass media, and bolstered by recent presidents: a Democrat, William Jefferson Clinton, who began his trek to the White House at Monticello, and a Republican, Ronald Reagan, who urged Americans to “pluck a flower from Thomas Jefferson’s life and wear it in our soul forever.” Both conservatives and liberals look to Jefferson as an icon and a role model.

The opening salvo is rhetorically cunning. Finkelman begins by giving Jefferson his due, only to create the impression in readers of his task in taking down Jefferson to be Herculean, so he becomes a modern-day demigod. And so here, as one anticipates, comes the qualifier: “Jefferson’s image in America would be almost perfect, were it not for slavery.”

Finkelman throughout his essay examines the relevant literature, pro and con, on Jefferson and slavery. The nodus, he makes clear, is that most of that literature is presentist: It assesses Jefferson from the standards of our time, not his. Finkelman aims to remedy that defect.

The difficulty is decupled because of Jefferson’s standing among historians. Jefferson was a man of many hats and of numerous outstanding deeds. Finkelman thus begins with a quote, often repeated, from nineteenth-century scholar James Parton to illustrate that difficulty:

If Jefferson was wrong, America is wrong. If America is right, Jefferson was right.

I admit that his oft-quoted passage has ever puzzled me, for wrong and right must be taken as mutually exclusive and mutually exhaustive, and if so, then the second claim, via modus tollens (“If ~J, then ~A” is logically equivalent to “If A, then J”) merely repeats the first, so why the redundancy? Parton’s point can merely be stated thus:

If American is politically on the right track (say, politically strong and just), then America is following Jefferson’s political creed.

Finkelman does not disagree with Parton. He merely aims to show that Jefferson himself did not follow his own political creed, and he begins by asking two questions:

(1) Did Jefferson take sexual advantage of Sally Hemings?

(2) If so, why then did he enslave his children?

He strangely does not return to those questions.

Finkelman gives a fair analysis of the relevant literature on the topic, but he singles out for especial criticism Alf Mapp. “Judged in the context of his times, Jefferson is relieved of the charge of hypocrisy,” says Mapp, who adds “it is extremely naive for us to judge him in the context of our time.” Finkelman, who agrees with Mapp on the eschewal of presentism, aims to take to task Mapp. Says Finkelman:

The question is not how Jefferson measures up to modern concepts of race and slavery but, rather, how he compares to three other standards: first, the portrayal of him offered by most of his biographers; second, the ideology and goals he set for himself; and third, the way his contemporaries dealt with slavery in the context of Jefferson’s ideals.

Two of the conditions, the final two, are reasonable. The first is subject to the objection that much of biographical literature that covers slavery is presentist.

Finkelman adds:

It is important, however, to understand Jefferson’s relationship to slavery and race on his terms and by the standards of his own era. A frank acknowledgment that understanding Jefferson affects how we understand our own world is not a presentism assessment of Jefferson. It is merely a recognition that history matters—something about which, presumably, all historians can agree.

While I agree with Finkelman, one wishes that Finkelman would explain why history, if not presentist, matters. I have my own reasons.

Finkelman ups his ante. Because of his greatness, we cannot hold Jefferson to the standard of being “better than the worst of his contemporaries,” but instead to the standard of “whether he was the leader of the best” of all Americans of his day, not just Southerners. In fine, if Jefferson articulates such-and-such ideals, but fails to live up to then, then he is a charlatan, not a political paladin.

The most prominent objection Finkelman has to Jeffersonian apologists is that they cherry pick. The tend to overpass the works of William Cohen, David Brion Davis, Winthrop D. Jordan, Robert McColley, John Chester Miller, and William W. Freehling.

Finkelman’s modus operandi is thus expressed:

Jefferson’s “hatred” of slavery was a peculiarly cramped kind of hatred. It was not so much slavery he hated as what it did to his society. This “hatred” took three forms. First, he hated what slavery did to whites. Second, he hated slavery because he feared it would lead to a rebellion that would destroy his society. Third, he hated slavery because it brought Africans to America and kept them there. None of these feelings motivated him to do anything about the institution.

I look at each of the three arguments from “hatred.”

First, Jefferson hated slavery because of what it did to Whites. Jefferson writes in Query XVIII of Notes on Virginia:

The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other.

Finkelman’s focus is the degradation of white slave-owners.

Jefferson also hated slavery because it made whites dependent on black slaves. Like others of his generation, he was particularly sensitive to the danger of dependency. Jefferson depended on his slaves as much as he believed they depended on him. He could not survive without his bondsmen and bondswomen, and he knew it.

What Finkelman fails to note is Jefferson’s claim that slavery makes despots of masters; his focus is on Whites’ dependency. A most convenient oversight on his part, n’est-ce pas? Concerning the “degrading submissions,” Finkelman says, “This sentence suggests that Jefferson may have been concerned about the effect of slavery on the slave.” No, the sentence is an assertion, not a suggestion! Jefferson also adds, “And with what execration should the statesman be loaded, who permitting one half the citizens to trample on the rights of another … and destroys the moral of the one part, and the amor patriae of the other.” The implication is that slaves are properly deserving of citizenship. Why does Finkelman omit that?

As I have noted—and somehow no one else in the world has ever notice this obvious observation—Jefferson does not use the language of color in his critique of slavery in Query XVIII. He writes merely of a corrupt and immoral institution.

Second, Finkelman then turns to Jefferson’s worry about a rebellion of slaves. He is correct. That was ever a concern for Jefferson, for the number of slaves was nearing the number of non-slaves (see Query VIII for Jefferson’s numbers). Jefferson writes in Query XVIII:

I tremble for my country, when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep forever: that considering numbers, nature and natural means only, a revolution of the wheel of fortune, an exchange of situation, is among possible events: that it may become probable by supernatural interference!

Again, Jefferson does not mention color, but adds this sentiment, “The Almighty has no attribute which can take side with us in such a contest,” which Finkelman again conveniently omits to strengthen his tendentious argument for Jefferson’s racism.

Third, there is “Jefferson’s profound racism”—a claim, given Finkelman’s promise to eschew presentism, must be shown true by the standards of Jefferson’s day. Jefferson hated Blacks, says Finkelman, and his assessment of them in Query XIV is proof. Says Finkelman:

His suggestion that blacks might inbreed with the “Oran-ootan” was laughable; his assertion that black men preferred white women was empirically not supportable.

Jefferson did assert that it was likely that Blacks were inferior to White in reason and imagination, but not in moral discernment—an enormous concession for a “racist.” That assessment was grounded in the early science of “race” in Jefferson’s day in the writing of men like Linnaeus, and Oliver Goldsmith, Cuvier. I invite people to read my chapter 3, titled “The Science of Race in Jefferson’s Day,” in my book Rethinking Thomas Jefferson’s Writings on Slavery and Race.) Linnaeus categorized orangutans as “Night Humans” (Homo nocturnus). Read also Voltaire’s Candide, where Candide shoots two orangutans, chasing two women from the jungle and he is informed by the all-wise Dr. Pangloss (All-Tongues or One of Many Languages) that the orangutans and women were lovers. In my book, I have a section titled “male Orangutans and Black Females,” which fully explains Jefferson’s “laughable” comments. Finkelman has not read Buffon, Linnaeus, and Goldsmith.

Overall, Finkelman says nothing of the numerous deeds of Jefferson in the effort to abolish slavery (see Abbeville essay and my essay in Abbeville’s Virginia First: The 1607 Project). I have argued that he did more than any other American of his time to eradicate slavery. Finkelman ignores Jefferson’s numerous anti-slavery bills and the tone of Query XVIII, which argues for the abolition of slavery. For him, the test is Jefferson’s reluctance to manumit all his slaves (a topic again I cover fully in my Abbeville essay).

Overall, Finkelman’s is a cunning essay, but he abundantly cherry picks his data—a peccancy of which he faults other scholars—and he fails to note any of Jefferson’s colossal efforts to rid of the foul institution of slavery.

“…comes the qualifier: ‘Jefferson’s image in America would be almost perfect, were it not for slavery.’”

As sure as the sun rises in the east and sets in the west, this qualifier is unread and untutored script from the liberal mind and the Yankee mindless. You might as well try to teach a rabid dog not to bite and bark or a skunk not to stink up the barn!!

Presentism is the fertilizer for these folks’ crops and fields.

Indeed, crambe repetita! Iterated and reiterated, and the folks continue to lap up that slop as if it could nourish. Politicized history does not nourish….. Thank you.

Your essays are always a good read and very enlightening. However, like Paul Finkelman, I struggle with Jefferson’s failure to free his own slaves. “For him [Finkelman], the test is Jefferson’s reluctance to manumit all his slaves (a topic again I cover fully in my Abbeville essay).” I read your linked Abbeville essay and did not find anything on this topic. Perhaps you are referring to another essay? In any event, I somewhere read that the poor state of Jefferson’s finances would not permit him to free his slaves. Perhaps you might comment on this.

BTW, I become more an admirer of Thomas Jefferson with each of these essays. Greatly appreciated.

~Steve, Richmond, VA

Thank you. Steve! 1. It was at one point in VA, illegal to free slaves. 2. Where would they go where they would be treated with dignity and assured of a livelihood? 3. He was, as you note, sorely in debt, and could not free slaves. Recall, owners had much $$$ invested in them.

I shall do a show on this topic in 3 weeks. Look for it. Thank you for your kind words….