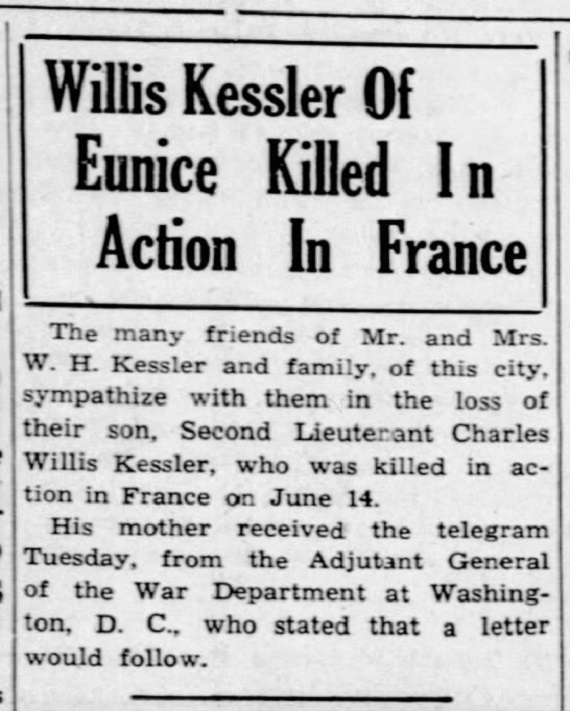

As Memorial Day approaches, I am thinking of a man I never met. His name is Charles Willis Kessler; he was a young, second Lieutenant from the small town of Eunice, Louisiana. Two of his brothers went to war also, one older, one younger. Both came home. Willis did not. He lost his life a few days after the Normandy Invasion when a Nazi sniper saw the bright flash of silver officer’s bars on his uniform and killed him with a single shot. His family received word that he had been buried in a small church yard in Mer St. Eglise, France. Nothing more. His mother never recovered.

Over forty years later, my family decided to find Willis. No one else in the family had ever visited his grave. We’d been touring France for over a week when we rented a car and drove to the village of Mer St. Eglise, a few miles from the coastline and close to the site of the Invasion. As we wandered through the churchyard, a priest came bustling out of the church and greeted us. He did not speak English, our French was spotty, but he spoke magic words “Cimetiere Americian Normandy.” We were off again barreling towards the Cemetery and Omaha Beach. What happened next made me proud to be an American.

The cemetery is extraordinarily beautiful and a stunning tribute to all persons lost in the terror of WWII, even those whose bodies were never found. We were welcomed warmly by the officer on duty. He ushered us into his office, found the location of Willis grave, and asked us to sign the visitors’ book, recording the names of all descendants of the hero soldiers buried there. He produced a beautiful bouquet and a bucket of sand and led us through a sea of gleaming white crosses and stars of David. They were beyond number. Suddenly there it was, Willis’s grave, his names carved in stark stone letters. His name, Kessler, was ours also. After a small ceremony, we placed the bouquet on Willis’ stone and sprinkled sand over the grave. Then photographs. I still have them as a reminder of that sweet, sad day. As we walked away from his grave, it was difficult to speak. Even our young teenage sons were quiet. On that day, we saw the meaning of incredible sacrifice from one of our own.

So, why did Willis go to war? What caused this young man fresh out of LSU to leave his home and volunteer to fight for his country. A few facts are clear. Pearl Harbor. Hitler’s ruthless invasion of Europe. The sinking of American ships as well as those of our allies. U-boats invading the North Atlantic with the intent to blockade all ships. The creeping realization that angry tyrants sought to take over the world. But I think his motivations were more than that. I believe they were deeply personal. It was a matter of survival, and the preservation of his way of life. Hot bowls of oatmeal his mother served her large family on cold winter mornings, as well as her homemade donuts. Watching his father walk to his job managing a sawmill. It was a job he chose to do, not one forced upon him. It was Willis’ small-town sensibilities, dedicated teachers, and Sunday meetings at Eunice’s Baptist Church, as well as a broadening of views when he entered college. Again, his choice, his future, his chance to shine.

He did not fight to affirm someone’s desire to control the free expression of ideas, parse speech, stamp out “unacceptable” words or advance the views of the easily offended who only offer their own brand of tyranny. That would have been unthinkable in his day. He did not give his life to encourages mob violence, censorship, or cut-throat politics. Again, unthinkable, even though memories of the Kingfish still echoed in Louisiana. He fought for the ideals he had been raised on and for the fear that his way of life would be taken away forever. Although his way of life may not have been more than a 5-mile radius around home, it was his and was worth fighting for to preserve and secure the blessings of liberty, for himself and his family.

As we returned to our car, another humbling event occurred. Several large, heavily loaded tour buses passed through the cemetery gates and stopped on the parking plaza. Surely, these were American’s coming to visit Normandy as we did. But no. This was different. Out of curiosity, we watched as hundreds of people streamed away from the buses and walked towards the cemetery. Many of the women carried flowers. The men spoke in loud voices, pointing and waving their arms as they described what had occurred on this sacred spot. All were French. They had come to remember the invasion and pay tribute to the Americans who died for their freedom. Viva Les Etats Unis!

“Time will not dim the glory of their deeds.” General John J. Pershing.

I write in honor and remembrance of Charles Willis Kessler of Eunice Louisiana, Second Lieutenant, 357 Infantry Regiment, 90th Infantry Division, who died on June 14, 1944. He was awarded a posthumous Purple Heart.