Like it or not, movies are the main art form of our time, the story-telling medium that reaches the largest audience and captures the attention of us all, high and low, wise and foolish. It is also true that movies, like literature and architecture, reflect something of the soul of the particular nation that produces them. If so, we indeed need to be concerned about the American soul.

Like it or not, movies are the main art form of our time, the story-telling medium that reaches the largest audience and captures the attention of us all, high and low, wise and foolish. It is also true that movies, like literature and architecture, reflect something of the soul of the particular nation that produces them. If so, we indeed need to be concerned about the American soul.

Until the late 60s, our cinema—whether contemporary or costume drama, comedy, Western, or war—reflected a general baseline of Middle American values. It was not usually great art but it was consoling entertainment and a source and reflection of a national consensus. And it portrayed with sympathy the real “diversity” of this far-flung Union—New England, the Big Apple, the Old South, the Midwest, and the West

The catastrophe known as The Sixties—marked by a collapse of morals, political fanaticism and violence, multiculturalism, and the ever tighter centralised control and enforced uniformity of all phases of life by the bicoastal elite, coincided with the degradation of the American cinema. Now we have godless nihilism and self-indulgence, violence for violence’s sake, every form of sexual promiscuity, filth for the sake of filth, and “creativity” generally limited to technological fantasy, sequels, prequels, dramatization of comic books, and rip-offs of European and Japanese stories. The masters of our multicultural monoculture have little talent but plenty of power and money and our cinema now reflects their minds and souls.

This is not the whole picture, of course. There are still “independent” productions that portray actual American people and situations and that manage to come to public attention. It is not difficult to produce a good book or a good movie. The problem is getting anyone to hear about it and to get it distributed. The mass media seldom reflect anything but what works our masters want to be celebrated and the absence of those works they want to be censored or ignored. All you need to remember is the reception give Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ” and Ron Maxwell’s historical epic “Gods and Generals.”

Amazingly and refreshingly, two excellent new and old-fashioned films, “Firetrail” and “The Last Confederate,” have appeared close together and are available on DVD. They doubtless have and will face the distribution problem, but they give a comforting indication of what American cinema could be if it were decentralised and reflected the true “diversity” of what is left of our real country. Real American culture has always been regional, for that is the only way that our vast Union can be fairly represented and where remnants of the real America are still to be found.

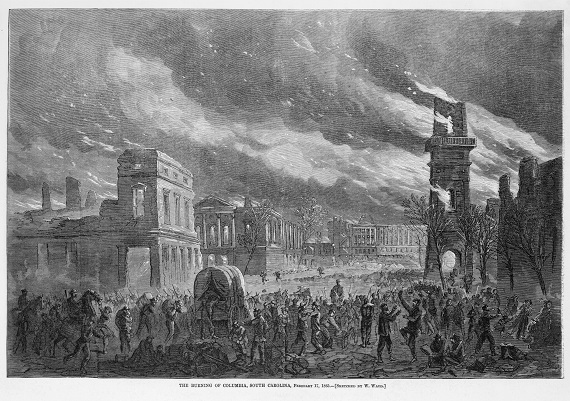

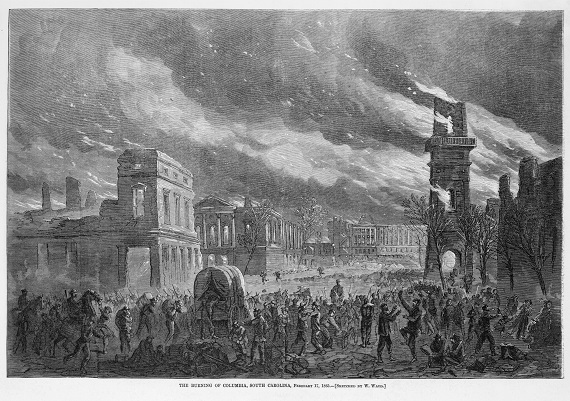

Both these films deal realistically and movingly with an unfashionable subject—the experiences of the people of South Carolina in the winter of 1865 when they became victims of the first large-scale American exercise of total war. (Something which is still denied by establishment historians but can be proved a thousand times over by the documents of the time.) General Sherman’s March is even yet regarded in some quarters as a great feat of arms and military genius. Actually, it involved little war other than skirmishes with outnumbered cavalry and home guards and was a calculated destruction of the means of civilian life—houses, private valuables and heirlooms, food, barns, crops, livestock, schools, churches, convents, whole towns. The high point being the deliberate torching of the surrendered and occupied city of Columbia, previously admired for its loveliness.

Both movies are products largely of regional inspiration and regional talent on both sides of the camera and reflect genuine regional memory, a thing rare in America and even rarer in the movies. Even some critics who have boggled at “nostalgia” for Southern traitors and slavers have acknowledged that the films carry a great deal of “authenticity.” And indeed they do. As renderings of historical experience they are faithful and subtly artistic. Costumes, action, dialogue, and personalities carry conviction as a representation of the real historical experience of certain Americans. Those audiences who have viewed them in limited release have been enthusiastic.

“Firetrail” is produced by the independent film-maker Christopher Forbes and based on the 2005 romance novel by ” Lydia Hawke,” though it rises far above that genre. The chief actors—Tripp Courtney and Jim Hilton as Confederate soldiers and Lin Laffitte as a beleaguered lady, are natives of the region, relatively unknown but with some “mainstream” film experience. They are excellent. So is the music from the Southern Rock group Beaver Creek.

“The Last Confederate” covers the same territory with similar virtues of authentic environment and native actors. Written, acted, and directed by Julian Adams, it is based on the experiences of his ancestors, Confederate Captain Robert Adams and his Northern bride Eveline McCord. These parts are played with skill by Julian Adams and Gwendolyn Edwards. I am a little, just a little, less enthusiastic about “The Last Confederate” than I am about “Firetrail.” The title “The Last Confederate” is inappropriate, there is too much genealogical pride, and Tippi Hedren and Mickey Rooney have needlessly been corralled in for small parts.

Some good news and a warning. The good news is that those responsible for both these films have in production other projects in the same vein. The warning: contemporary manners-challenged Americans might find the dialogue a little slow and stilted. But it captures truly the times and people portrayed. In those days they understood what George Garrett has written: that manners are a recognition that our fellow human creatures, all of them, are made in the image of God.

SOURCE: A slightly different version appeared in Chronicles: A Magazine of American Culture, July 2010.