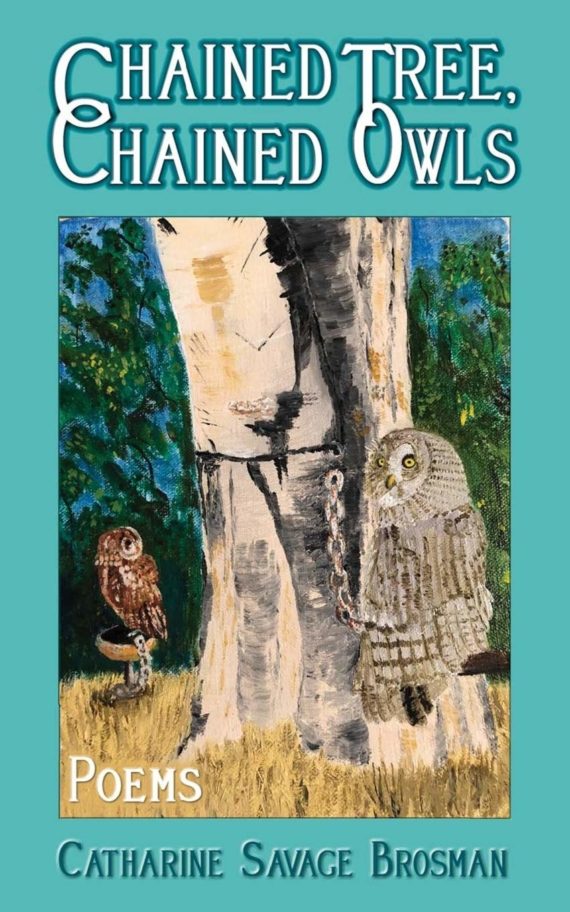

A Review of Chained Tree, Chained Owls, Poems (Green Altar Books, 2020) by Catharine Savage Brosman.

This is Catharine Savage Brosman’s twelfth book of poems, and the praise for her work has increased with each new publication. This review will follow suit; and in order to demonstrate– to point out clearly– this new level of excellence, it is best to remind ourselves what all poetry should do, no matter the beauty of the language, the mastery of technique, or the inspiration it renders.

W.H. Auden is famous for saying that most people think that great art is meant to enchant, whereas it is meant to do the opposite. It is meant to disenchant. The closing lines of Canto V of Dante’s Paradiso are a good example of what Auden meant. There the poet offers the standard symbol of the sun standing for God. As God spreads His rays lovingly upon all, warming hearts, minds, and souls, so the sun spreads its rays upon all. Thus, the symbol draws the reader into a charmed, enchanted world, and the reader is prepared to imagine himself or herself following Pilgrim Dante in his journey through heaven. But then Poet-Dante throws the reader the true poet’s curve ball. He asks the reader to look closely at the sun– even stare at it– as one would actually behold it on earth. Now, far from painting a golden disc of warmth blessing all and inviting us to imagine a sojourn in Heaven, the poet’s words show us instead the broiling turmoil of heat and light so dangerous to look at. Poetic genius then is free to strike. Dante makes the reader see that the broiling turmoil of the sun really looks as if it is fitfully struggling not to burn our eyes; as if it is doing all within its power to conceal its rage and save the beholder. Fantasy Land is now gone. God, by way of this symbol, crosses our path; for the power that burns now is the power of Grace.

Great poetry clarifies and focuses our vision in this way. Symbols are made up of superb description so that what we see matches what the poet sees, and thus both the vision and the meaning are ours, and ours now as if we had only momentarily forgotten them.

It follows that the true poet is not only the great disenchanter, but also the best of all teachers. For if there has occurred a return of the mind back to the given world then the poet as exorcist (so to speak) and poet as professor fit together hand in glove.

Sir Philip Sidney, the poet-soldier who died in battle, said in his essay of 1595, “In Defence of Poesie,” that…

“As virtue is the most excellent resting place for all worldly learning…, so poetry, being the most familiar to teach it, and the most princely to move towards it, in the most excellent work is the most excellent workman.”

Such sound reasoning of course has no place in our culture, not with the reigning enchanters of postmodern, Marxist, feminist and other such “critics.” Dr. Brosman has written her own “In Defence of Poesie” (found in her book Music From The Lake And Other Essays) where she argues like a warrior that great verse indeed renders “knowledge, experience, and morality.” And like Sir Philip, who said a few pages after the lines quoted above, “poetry maketh kings fear to be tyrants,” and then (quoting the Roman Stoic Seneca) the poet makes “terror return to its agent,” Dr. Brosman likewise warns our current ideological despots.

Consider her poem “On Lee Circle, New Orleans.”

A foul fait accompli, an altered view.

As usual, fanatics are to blame,

and egos gratified by much ado.

But Lee, at least, will always be a name;

we cannot say the same for you, Landrieu.

A careful reader should notice right off the bat that the fait accompli announced in the first verse is not the destruction of the statue of Robert E. Lee, but Mayor Landrieu’s destruction of his own name in approving and applauding the public vandalism. We know this first of all because the familiar French expression does not simply signal that a deed is done; the phrase instead carries a strong ring of finality, as in Shakespeare’s “what’s done cannot be undone.” And we know this also because (line four) Lee’s name is permanent. Deeds like his live on in his name. But the mayor’s name carries along no real deed at all, only some old happen-so, any old “much ado” (line three), and so will soon be forgotten. I am sure Dr. Brosman also meant for this “much ado” to echo Shakespeare’s “much ado about nothing.” Thus, the poem renders knowledge, experience, and especially morality: “terror returns to its agent,” to cite again Sir Philip Sidney’s use of Seneca’s words. And finally, the “altered view” in the first line is simply a gap, a lack, a privation, just like Landrieu’s name.

There are some 70 poems in this volume. Sixteen of them are also translated into French (and exquisite French at that. They stand up on their own.). Eight are about the destruction of Confederate monuments, plaques, and threats to do away with libraries and even Southerners themselves. All of them penetrate to the empty heart and brain of the destroyers, reminders that for much of Classical and Christian moral theory evil is a privation. For instance, in “Site of Jefferson Davis Memorial, Canal Street” the poet gives the collective name “Take ‘Em Down” to those whose delight in verse that goes no further than Hey Hey, Ho Ho. Like Landrieu, they too have no name. They demand public action as if they had great authority, but never dared to face the public. Linguist that she is, Dr. Brosman knows that the word “idiotes” is the Greek designation for those who have no public life. Here is the poem:

There’s not much left; the pedestal and base,

the man himself, are gone, removed at night

by “Take ‘Em Down,” which didn’t dare to face

the public. Yankees always had it right–

So like today’s, who feast on our disgrace.

We see again the sign of idiocy, emptiness, and privation in the poem “Prologue.” Here the non-public-public fierce demand is for “laundering” brains, for condemning the past to oblivion. But vis a vis this right, Dr. Brosman asks, how can we repent if nothing is remembered? These people are not simply idiots, they are “insane.” Here is the poem.

The New People’s Republic has launched its campaign,

much like Stalin and Hitler, like Mao, Pol Pot,

to remove all that’s harmful, to launder my brain,

tear down statues, change language, impose tommyrot.

We must wipe out the past and repent. It’s insane!

Where I live, the Confederate statue that guarded the Albemarle County Courthouse was recently removed. After the removal, amidst wild cheering, a gleaming and prancing soul came forward with a watering can and performed what she must have thought was some sort of baptism, a cleansing of what she took to be our sins of the past. But if the past can be erased and our minds “laundered,” this person performed no such ritual. She simply took on the role of street cleaner–and another enchanted moment became disenchanted.

In her essay “In Defence of Poesie” Dr. Brosman describes poetry as “an order (of language) within an order.” Within the order of the verses–the diction, the carefully chosen words, the rhythm and rhymes, the syntax and alliterations– can be found another order which structures and gives rise to the apprehension of the meaning of the first. We have seen that poetic meaning for her is three-fold, knowledge, experience, and morality. In her poem < [remove comma] “Montaigne,” found in this volume, she calls this slow piecing together of the second order the “drawing out of wisdom’s flower.” The “whole piece” is judged by “this pattern”, as the novelist Henry James put it.

Each poem in this volume has a first order of five lines (which she calls a quintain) with an ababa rhyme scheme. The repetition of rhythm and “flowering” as one turns page after page makes for an enduring joy. The whole world is disenchanted and rediscovered. She snaps new wisdom into the mind by looking at mountain ranges, rivers, cathedrals, friends, monuments and mobs–even spaces themselves; and half-way through this collection we conclude she could rid us of our idols by observing for us just about anything.

Here is one of her title pieces.

“Chained Owls”

Athena’s birds perch, tethered fast by rope

or chain, forlorn, displayed against their will

for our amusement. By an avian hope

they try their wings, again, again, yet still

no flight, no grace–fate’s pained, despairing trope.

Athena is the Goddess of Wisdom. Readers can look up the name if they have forgotten this, but how in the world can owls be Lady Wisdom’s inspiration on earth as, say, the dove in the Gospels is God’s Spirit on earth? How can the owl be the bringer of Wisdom down to earth and with it cross our path? Owls, for us, are bug-eyed midnight spooks that rarely even move; or if they inspire at all it is only wall-eyed drunks (to call to mind an old saying from where I grew up–”drunker than a hoot owl”). But we learn in this extraordinary poem that they do inspire because our “amusement” vanishes when we become readers and experience the “avian hope” that won’t stop tugging at the tether. As we see ourselves in Christ’s struggle on the cross, so we know the heights from which we have fallen when we know the depths into which we have landed. The birds’ “fate” is indeed a “despairing trope,” which pulverizes all delusions.

I judge this last poem to be the best. It needs little comment.

“Notre Dame de Chartres”

It’s asymmetrical, a brief surprise,

admired, although, always, saints look odd–

stone-pocked, niched awkwardly, as if with eyes

apart from life, intent on only God.

That stern gaze is the vision of the wise.

Saints look like stone monuments, pock-marked, stern, and weatherbeaten.

This is one of her “happier” poems, but still passes a fierce judgment upon us. Thank God this one monument remains standing.

Dr. Brosman calls her twelfth book of verse an aide-mémoire. We encounter her wisdom as if it were our own–as if we had only momentarily forgotten it.