During the past few decades, there has been an ever-growing sentiment throughout the Unites Sates to erase from the public mind, if not from American history itself, all vestiges of the Confederate States of America, and in particular, all memorials dedicated to the heroes, leaders and symbols of the Lost Cause. Following the senseless murder of a number of African-American churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, two years ago, and this year’s fatal riots in Charlottesville, Virginia, the mounting cry to remove most, if not all, of the more than fifteen hundred Confederate statues and memorials located in twenty-seven states, both North and South and the District of Columbia, has developed into a raucous harangue that has led to the legislative, as well as the vandalistic, removal of a number of those monuments. Most Americans undoubtedly believe that such memorials are unique to the South and while over twelve hundred are properly located in the eleven states of the former Confederacy, the remaining three hundred are scattered throughout the North, including a monument placed in Boston Harbor by the Massachusetts chapter of the Daughters of the Confederacy over a half century ago to honor the thirteen Confederate prisoners of war who died in Fort Warren on Georges Island. There are even Confederate memorials in such unlikely places as British Bermuda and Sao Paulo, Brazil.

The movement to “pull old Dixie down,” however, goes far beyond the current rush to remove flags, statues and memorials . . . it is, and has long been, aimed at the total rewriting of American history through the kaleidoscopic prism of changing social values and mores. As was the case in the former Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany, if actual history tends to inconveniently contradict current ideology, then merely rewrite any facts that are objectionable. This, unfortunately, has been true in reference to the actual causes of the Civil War, a term that did not even come into popular usage until almost the beginning of the Twentieth Century. During the War itself, the North generally referred to the conflict as the “War of the Rebellion,” while those in the South preferred such terms as the “War for Southern Independence” or “War of Northern Aggression.” A few times President Lincoln did refer to the conflict as “a civil war,” but never the Civil War. Some of these occasions were in his 1861 proclamation calling for a day of fasting, another was his special message to Congress in 1862 and, of course, it was mentioned in his well-known address at Gettysburg in 1863. It was in the 1862 message to Congress, however, in which the blurring of historical facts actually had its roots, and for a very self-serving purpose . . . Lincoln’s defense of the War, as well as the actions of certain members of the Cabinet in carrying out his wishes.

The message itself was ostensibly in reply to a vote of censure against Lincoln’s former Secretary of War, Simon Cameron, in connection with the misappropriation of millions of dollars in federal funds at the very beginning of the War by Cameron’s purchasing agent, Alexander Cummings. The censure vote had taken place following an almost year-long investigation into such matters by the House Select Committee on Government Contracts headed by Representative Charles Van Wyck of New York. In reporting the Committee’s findings to Congress, Van Wyck stated “the mania for stealing seems to have run through all the relations of government” including “those nearest the throne of power.” Due to the investigation, Cummings was dismissed from his position in the War Department and Cameron was forced to resign from the Cabinet. Even though Cameron’s dishonesty was such that one radical Republican congressman, Thaddeus Stevens, once commented to President Lincoln that Cameron was one who would steal “a red hot stove,” the president named him as the U. S. Minister to Russia. As for Cummings, he later headed a Pennsylvania cavalry unit, and was finally posted as a Superintendent of Colored Troops with the rank of brigadier general. Immediately following the War, Cummings was appointed by President Andrew Johnson as governor of the Colorado Territory . . . who said crime does not pay! Lincoln’s defense of Cameron and Cummings, however, only came after he had presented a lengthy defense of his own initial actions in connection with the War.

In his message to Congress, Lincoln wrote that the South’s actions were merely a “clandestine insurrection” aimed “at the overthrow of the Federal Constitution and the Union” by an “organization in the form of a treasonable provisional government at Montgomery in Alabama” Furthermore, with no mention of his secret and war-provoking order to try and smuggle reinforcements and supplies to Fort Sumter in Charleston via an unarmed ship prior to the shelling of the fort, Lincoln went on to say that “the insurgents committed the flagrant act of civil war by the bombardment and capture of Fort Sumter, which cut off the hope of immediate conciliation.” In this, the president also neglected to mention to Congress his rebuff of all efforts by the Confederacy to negotiate a peaceful compromise to the rising tensions and talk of war. Lincoln then made the completely false statement that because Washington had been “put into a condition of siege,” he was forced to act quickly to stop “the government from falling at once into ruin” by issuing calls for military forces and munitions, as well as $2 million in secret federal funds to finance such operations. On the latter, Lincoln specially defended the actions of Secretary Cameron and his purchasing agent by adding that the need for secrecy and the awarding of huge military contracts without any public bidding was due to the fact that “several Departments of the Government contained so large a number of disloyal persons” he had to entrust all matters to only those few who were “known for their loyalty and patriotism.”

Thus had Lincoln set the stage for the Northern version of how the War had been started solely by the treasonous South, and how his administration had saved the country in 1861 by its timely, even if unsanctioned, unauthorized and possibly criminal, actions. In later years, this initial rewriting of history as to how the Union had been saved and the traitors thwarted was further compounded by the added fiction which is so popular today . . . that the War was fought to free the slaves. Today, most knowledgeable historians, even those who find little or no fault with the Northern version of the War, are forced to admit that while slavery was certainly one of the basic causes of the conflict, it is a false assumption that the Union invaded the South mainly to free the slaves. There were, of course, various abolitionists who desired such an action, but the majority of those in the North, including President Lincoln himself, were perfectly willing to allow slavery to continue if the Southern States agreed to dissolve the Confederacy and rejoin the Union. Some, such as the Union’s commanding general, U. S. Grant, even went further by saying if freeing the slaves had been the primary rationale for all the conflict’s misery and bloodshed, he would have offered his sword to the South. Even in issuing his slavery proclamation in 1863, Lincoln, who had initially preferred colonization in Africa for America’s slaves, admitted the edict was merely a wartime measure to weaken the South. Furthermore, few today who now hail Lincoln as the “Great Emancipator” because of his proclamation have ever taken the time to actually read the document. If they had, it would quickly become evident to them that the “freedom” Lincoln advocated pertained only to the slaves in those areas of the Confederacy over which the Union had no control whatsoever. In the areas of the South then held by Union troops, as well as in the various Southern states which had remained in the Union, slavery, under the terms of the proclamation, was to remain firmly in place. Slavery itself was not finally abolished until the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution became effective over half a year after Lincoln had been assassinated and the South had surrendered.

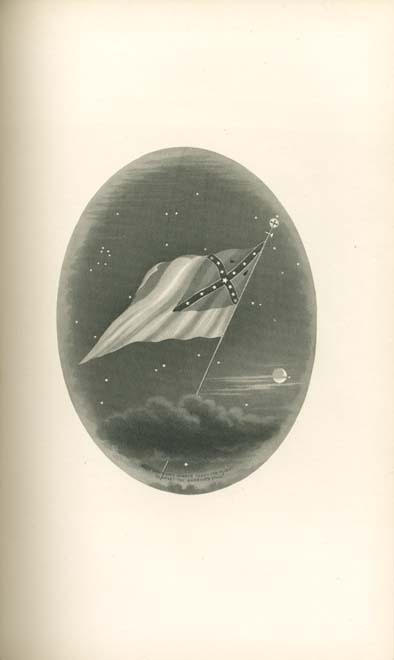

Just after General Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House on April 12, 1865, exactly four years after the opening guns of the War were fired in Charleston Harbor, a Catholic Priest who had served as a freelance chaplain with the Army of Tennessee, Father Abram Joseph Ryan, penned a fitting cadenza to the final end of hostilities entitled “The Conquered Banner.” This epic poem of the South has been favorably compared to Ralph Waldo Emerson’s classic “Concord Hymn” which commemorated the 1837 dedication of the Revolutionary War memorial at Concord, Massachusetts, and in which the phrase “the shot heard around the world” became forever immortalized. While Father Ryan’s mournful dirge also advocated the current call to furl the Confederate Battle Flag, his reasons were diametrically opposed to what is meant today by those who wish to eradicate anything dealing with the Confederacy. Rather than what people now consider to be a symbol of hatred and slavery, Father Ryan’s banner was one that had been proudly borne by Southern soldiers during what General Lee had termed at Appomattox as “four years of arduous service marked by unsurpassed courage and fortitude.” Some of the closing lines of Father Ryan’s verse would seem to sum up how many in the South, as well as elsewhere in the nation, truly regard the memory of the conquered Confederate banner:

Furl that Banner, softly, slowly!

Treat it gently — it is holy,

For it droops above the dead.