Before there was any New England in the North, there was something very like Old England in the South. Relatively speaking, there is still – G. K. Chesterton

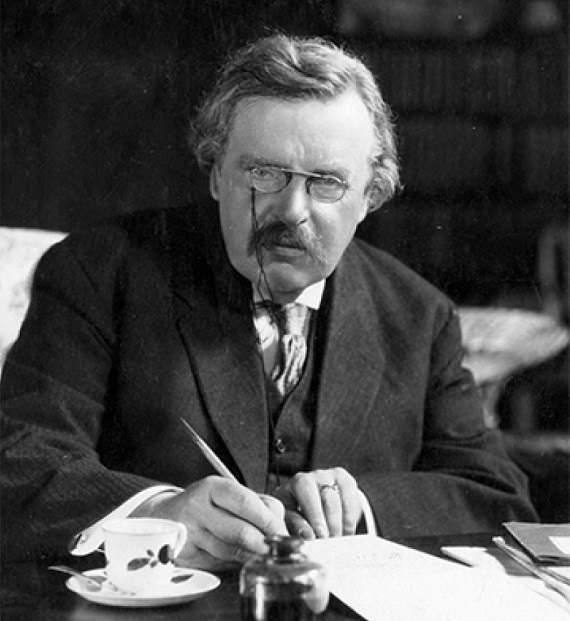

Within Christian and conservative circles, the great English writer Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874-1936) is widely considered one of the most important authors of the Twentieth Century. As a poet, novelist, mystery writer, journalist and Christian apologist Chesterton excelled; presenting a formidable challenge to the encroaching progressivism and secularism to which the greater part of the English speaking world has succumb. In many ways Chesterton embodies the best of the conservatism of Edmund Burke together with the classical liberal democratic ideals of the old English Whigs. Among the pillars of the edifice constructed by Chesterton’s thought are: an emphasis on the classical Natural Law tradition, a tremendous respect for the old Roman Republic and civilization, and a devotion to orthodox/creedal Christianity.

Many people know that Chesterton’s writings were a prominent influence in C.S. Lewis’ conversion to Christian faith, and I will go so far as to affectionately classify Lewis’ writings as – G. K. Chesterton for dummies. In this respect many people who are not acquainted with Chesterton’s works have been influenced by other writers who were themselves students of that giant of a man oft hailed as the Apostle of Common Sense; to name but a few: Dorothy Sayers, Russell Kirk, T. S. Eliot, William F. Buckley, Flannery O’Connor and J.R.R. Tolkien.

As an advocate for Tradition with a capital “T” and the family as the fundamental building block of society, Chesterton is credited with one of the most penetrating definitions of that sometimes misused and misunderstood idea we regularly refer to as “conservatism.” Russell Kirk elaborated on principle six of his ten point 1952 essay What is Conservatism?: “The conservative appeals beyond the rash opinion of the hour to what Chesterton called the democracy of the dead —that is, the considered opinions of the wise men and women who died before our time, the experience of the race. The conservative, in short, knows he was not born yesterday.” Chesterton wrote in his masterpiece Orthodoxy:

Tradition means giving a vote to that most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about. All democrats object to men being disqualified by the accident of birth; tradition objects to their being disqualified by the accident of death. Democracy tells us not to neglect a good man’s opinion, even if he is our groom; tradition asks us not to neglect a good man’s opinion, even if he is our father. (Orthodoxy; Chapter 4; 1908)

This brings us squarely where we need to be to understand Chesterton’s thoughts concerning the American South. While Chesterton may have gone through a self-conscious phase of knee jerk British Imperialism, his reading of British antiquity steered him rather in the direction of federalism and home rule. So for example, Chesterton as an historian agreed that the British American Colonies could and should secede and self-govern, and in his own day he had strong sympathies with the Southern Irish cause. He definitely saw the threat that Centralized Nationalism in the form of the modern State was to family, culture, and Church. Indeed, by extension to society and civilization itself. And Chesterton believed that the rural backbone of Great Britain was a major factor in their many centuries’ long retention of freedom and self-sufficiency. Like Thomas Jefferson, Chesterton knew the link of private property rights to independence and so he advocated the widespread ownership of land by the general citizenry while warning of the dangers of urbanization and industrialization. For him it was obvious that the British yeoman was safer, happier and enjoyed more freedom living in rural areas under Squire or Clan Chief, then when they left the Shire to move into the cities. Thus Chesterton is a kindred thinker with our Southern Agrarians. Chesterton wrote:

These are not days in which it is exactly obvious that an agricultural society was more dangerous than an industrial one. And even Southern slavery had this one moral merit, that it was decadent; it has this one historic advantage, that it is dead. The Northern slavery, industrial slavery, or what is called wage slavery, is not decaying but increasing; and the end of it is not yet. (What I Saw In America; Chapter 13; 1922)

When Chesterton wrote his book What I saw in America, he referred to the Northern Cities of the United States as “forests of brick” and a “labyrinth of lifeless things.” What may seem strange to many contemporary American conservatives is that Chesterton was not surprised to see progressivism, crony capitalism and urbanization running amuck in the Northern portion of the United States, as he saw this as the logical terminus of the apostate Puritan. He noted that “New England” is the least like “Old England” of the former colonies. And he wished to despoil the myth of the Pilgrims as pioneers of religious liberty, observing that “there is no doubt that the note of their whole experiment in New England was intolerance, and even inquisition.” Chesterton goes on to say:

And there is no doubt that New England was then only the newest and not the oldest of these colonial experiments. At least two Cavaliers had been in the field before any Puritans. And they had carried with them much more of the atmosphere and nature of the normal Englishman than any Puritan could possibly carry. They had established it especially in Virginia, which had been founded by a great Elizabethan and named after the great Elizabeth. Before there was any New England in the North, there was something very like Old England in the South. Relatively speaking, there is still. (What I Saw in America; Chapter 13)

Fascinatingly, Chesterton turns his critique to the cult like status of Abraham Lincoln humorously observing: “Lincoln was quite un-English, was indeed the very reverse of English; and can be understood better if we think of him as a Frenchman…” And interestingly when it comes to Lincoln’s role as the great emancipator Chesterton casually and correctly comments that at best Old Abe held a certain “moderation in face of the problem of slavery.” When considering R. E. Lee, Chesterton imagines him as Hector defending Troy:

Long ago I wrote a protest in which I asked why Englishmen had forgotten the great state of Virginia, the first in foundation and long the first in leadership; and why a few crabbed Nonconformists should have the right to erase a record that begins with Raleigh and ends with Lee, and incidentally includes Washington. The great state of Virginia was the backbone of America until it was broken in the Civil War. From Virginia came the first great Presidents and most of the Fathers of the Republic. Its adherence to the Southern side in the war made it a great war, and for a long time a doubtful war. And in the leader of the Southern armies it produced what is perhaps the one modern figure that may come to shine like St. Louis in the lost battle, or Hector dying before holy Troy. …Old England can still be faintly traced in Old Dixie. It contains some of the best things that England herself has had, and therefore (of course) the things that England herself has lost, or is trying to lose. But above all, as I have said, there are people in these places whose historic memories and family traditions really hold them to us, not by alliance but by affection… England once sympathised with the South. The South still sympathises with England. (What I Saw In America; Chapter 13)

Chesterton wrote in Chapter 36 of his book Come to think of It that “the American Civil War was a war between two civilizations” and that “it will affect the whole history of the world.” He seemed to conceive that just as Lincoln loosened the “lightning of His terrible swift sword” in America, scarcely a Continental European Duchy or Fiefdom would be safe from the expansion of the new European Mega States marking a trajectory to our modern age.

Chesterton also understood the War Between the States as a Northern “conquest”, and I imagine he felt that the defeated South abides under the post-war nationalism rather like the Saxons and Celts under Norman control – thus linking the defeat at Appomattox to those of Hastings and Culloden. More than a mere romantic fancy, I mean to imply that contemporary conservative Americans from coast to coast may have some inkling of this feeling in our own time, regardless of which political party is in power. And just as the Highlanders who sided with the Bonnie Prince were denied the basic British Constitutional right to bear arms and prohibited from wearing their Clan Tartan’s, there is a striking similarity when we are told not to fly our old battle flag – the Southern Cross of St. Andrew – it being itself a variation of the flag those Highlanders carried in 1745.The St. Andrew’s Cross was dear to the Scots-Irish of the Appalachian backcountry and also to English Cavalier’s of Virginia who fought for another Stuart King a century before Culloden.

Once more in What I Saw in America, Chesterton acknowledges the pending doom that he sees as the crushing of the “English spirit.” This idea seems sharpened to his senses by the Anglophile South where he says the English traveler finds “Nashville containing people more pro-English than Englishmen” and “Virginians not only of British blood, like George Washington, but of British opinion almost worthy of George the Third.” Writes Chesterton:

That is why I insist on the stupidity of ignoring and insulting the opinions of those few Virginians and other Southerners who really have some inherited notion of why Englishmen love England; and even love it in something of the same fashion themselves. Politicians who do not know the English spirit when they see it at home, cannot of course be expected to recognise it abroad. Publicists are eloquently praising Abraham Lincoln, for all the wrong reasons; but fundamentally for that worst and vilest of all reasons—that he succeeded. None of them seems to have the least notion of how to look for England in England; and they would see something fantastic in the figure of a traveller who found it elsewhere, or anywhere but in New England. And it is well, perhaps, that they have not yet found England where it is hidden in England; for if they found it, they would kill it. (What I saw in America; Chapter 13)

In an age when friend and foe alike hasten to remove the ancient landmarks (Proverbs 22:28), the great Gilbert Keith beckons us to follow the old paths (Jeremiah 6:16); not forgetting those values “for which the world was immeasurably the better.”

The world will need, and need desperately, the particular spirit of the landowner who will not sell his land, of the shopkeeper who will not sell his shop, of the private man who will not be bullied or bribed into being part of a public combination; of what our fathers meant by the free man. And we need the Southern gentleman more than the English or French or Spanish gentleman. For the aristocrat of Old Dixie, with all his faults and inconsistencies, did understand what the gentleman of Old Europe generally did not. He did understand the Republican ideal, the notion of the Citizen as it was understood among the noblest of the pagans. That combination of ideal democracy with real chivalry was a particular blend for which the world was immeasurably the better; and for the loss of which it is immeasurably the worse. It may never be recovered; but it will certainly be missed. (Come to Think of It; Chapter 36; 1930)