As editor-in-Chief of the inaugural issue of the now-defunct theme-based journal, The Journal of Thomas Jefferson’s Life and Times, I was asked to write the feature, introductory essay, which I titled “‘A silent execution of duty’: The Republican Pen of Thomas Jefferson.” It was a daunting task, as I aimed to introduce the journal by constructing an essay that would give readers some feel for the breadth and depth of Jefferson’s mind. Given the obvious spatial constraints, there were two available paths. On the one hand, I could focus on Jefferson’s intellectual breadth by giving a relatively exhaustive account of his interests and saying little about each. On the other hand, I could focus on Jefferson’s intellectual depth by introducing readers to a handful of his interests and going into some detail on each of them. The advantages, and disadvantages, of each approach are sufficiently plain so that no discussion of them is needed. I chose the latter.

On finishing the essay, I became frustrated that I had not done justice to the categories I had culled—Jefferson as liberal revolutionist, utopist, natural scientist, and moralist—which were in some sense culled arbitrarily. Thus, I promised myself that in the near future, I would give Jefferson’s large and singular mind the scholarly attention it merits—hence, my book, The Cavernous Mind of Thomas Jefferson, An American Savant. In that book, I have chapters on Jefferson as lawyer, moralist, politician, scientist, epistolist (letter-writer), aesthetician, farmer, educationalist, and philologue, and those nine chapters still do not fully Jefferson’s cavernous mind: e.g., I say nothing about Jefferson’s passions for and expertise in music and architecture.

How does one go about capturing the mind of an extraordinary character like Thomas Jefferson?

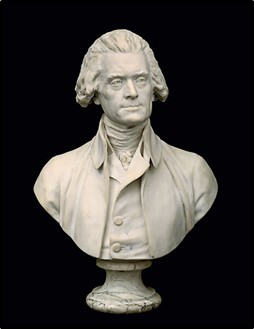

Biographer Henry Adams, in his History of the United States during the First Administration of America, during the First Administration of Thomas Jefferson, offers this cautionary advice. “A few broad strokes of the brush would paint the portraits of all the early Presidents with this exception, and a few more strokes would answer for any member of their many cabinets; but Jefferson could be painted only touch by touch, with a fine pencil, and the perfection of the likeness depended upon the shifting and uncertain flicker of its semi-transparent shadows.” The sentiment—poetic, almost impenetrably so—bespeaks large, perhaps matchless, complexity of personhood. Jefferson’s portraiture, Adams’ words imply, is a task for no ordinary artist, but one with equal, or nearly so, complexity—otherwise there can be no detailing with the fine pencil.

The scenario is more complicated. Scholars today often lament that we cannot get at the historical Jefferson even with a fine pencil. It is commonly asserted that Jefferson was slippery and deceptious in his writings—especially his letters—that he aimed to placate correspondents by writing what they wished to hear, not what he believed to be true. Thus, the argument goes, it is nearly impossible to know the person behind the pen. One writer, Pete Onuf, goes so far to say that so great was Jefferson’s slipperiness and deceptiveness that we cannot know the person behind the pen.

Thomas Jefferson loved to write. That is how he best expressed himself. His correspondence consists of some 19,000 letters. He drafted numerous bills; wrote several addresses, reports, messages, proposals, replies, and directives as a public servant; began a late-in-life autobiography (which he never finished); wrote critical essays or commentaries; wrote a book; and usually took notes when he travelled in the event that any of his observations should prove serviceable at some future time. Jefferson writes in his autobiography:

I have always made it a practice whenever an opportunity occurred of obtaining any information of our country, which might be of use to me in any station public or private, to commit it to writing. These memoranda were on loose papers, bundled up without order, and difficult of recurrence when I had occasion for a particular one.

Last, he even wrote his own epitaph. And so, to know best Jefferson, one has to know well his writings and one has to study the things that he studied.

The task is not Gordian, but instead complex. Jefferson, I believe, was not so protean and deceptive, as biographer after biographer seems to say these days. He is a difficult task for a biographer who wishes to get at the man not because of his slipperiness, but because of his dimensionality—his numerous and varied interests—and his politeness—he would speak to others of things in which they, not he, took especial interest. Jefferson was many things to many persons because he was many things. He was a person of extraordinary depth and breadth.

Like no president before or after him, Jefferson was omnilegent, or nearly so. He had one of the largest libraries in the young nation and it was not for show, but for use. As his library swelled in size, so too did his mind. He was not only well-read, but knowledgeable in numerous subjects: e.g., law, architecture, agriculture, gadgetry and invention, paleontology, music, political practice and theory, education, Classics, philosophy, history, religion, philology, and literary criticism. Hence, we can grasp the poignancy of John F. Kennedy’s remark on April 29, 1962, at a White House dinner party in honor of Nobel Prize winners, “I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.”

If it is the case that Jefferson’s cavernous mind is the chief reason that he can be portrayed only with a fine pencil, then aiming to understand Jefferson by exposition of the most prominent aspects of his mind—e.g., his interests in law, in philosophy, in husbandry, in language, in beauty, and in science—offers any Jefferson scholar the best chance of grasping him. That is what I aimed to do in my book The Cavernous Mind of Thoams Jefferson.

That Jefferson had a keen interest in such diversity of subjects is not a matter of a mercurial appetite—as it were, a fussy stomach that is easily bored with flavors—or political intrigue—viz., pandering to others for political gain. Jefferson had a profound interest in the human condition and in humans’ fit in cosmic affairs. And so, he was a man who, when he took interest in something, dove into that subject with a vigor, focus, and enthusiasm that too few persons possess. Moreover, convinced of cosmic purposiveness, Jefferson needed to know how the things he examined fit together. Ever dissatisfied with the appearance of truth—verisimilitude or truthiness—he aimed always at a full grasp or understanding of things. Like too few others of his day, he was a true student—to my mind the best example from America—of the Enlightenment.

Yet today’s world is markedly different from Jefferson’s. Ours is an age of specialization. Cosmic purposiveness, a teleological concern, is passé. The sciences, seen as working together to offer a depiction of cosmic intention, have become dissociated and particularized. We care not whether the sciences are complementary, so long as each solves problems it aims to solve in its own way. In business, we are educated to perform a particular task at a corporation and not to worry about how the business as a whole works. All is well, if at week’s end, we get our paycheck.

Jefferson’s time, in sharp contrast, was an age of wonder, excitement, and unity of purpose, due to belief in scientific progress and, for many, cosmic goodness. That is why Jefferson insisted that professors at the University of Virginia were to be expert specialists in their own field, but also men who could converse intelligently on all other fields of science. That scholarly ideal is foreign to us. Ours is an age of perplexity and apathy, as our cosmos is indifferent to the fate of humans. We are willing to contribute to the public good or listen to the advice of scientific researchers, all specialists, so long as we can be sure that there is something in it for us. Thus, the differences between Jefferson’s time and ours are in large part responsible for Jefferson’s inaccessibility to us.

Because his interests were so broad, he is for many of today’s scholars a comical, naïve, or at least perplexing figure. Yet to be wholly understood, Jefferson cannot be measured by today’s precise, but limited tools of the particular sciences. Doing so, we completely miss the measure of the man. That egregious mistake is captured beautifully by philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein in his booklet that comes down to us as On Certainty. A painting is made to be appreciated from a certain distance, says he. We gain no finer appreciation of that work of art by standing inches from it and staring at its “particulars”—a shot, unfortunately, at analytical philosophers such as me.

And so, to understand Jefferson as a person consisting of varied personae—to understand the cavernous mind of Thomas Jefferson—we must make an especial effort to see how those personae hang together, and they do hang together. We must see Jefferson as a whole, at a certain distance, and from his own Zeitgeist, not ours. Otherwise, the various personae will make him appear to be a comical, naïve, and perplexing figure—that is the tack of many of today’s denigrative Jeffersonian scholars—when he was a man of clarity of vision and unity of focus.

Enjoy the video below….

Great article on a great man. ..my favorite Founder.

Thank you!

Thank you, Keith, for your kind words!