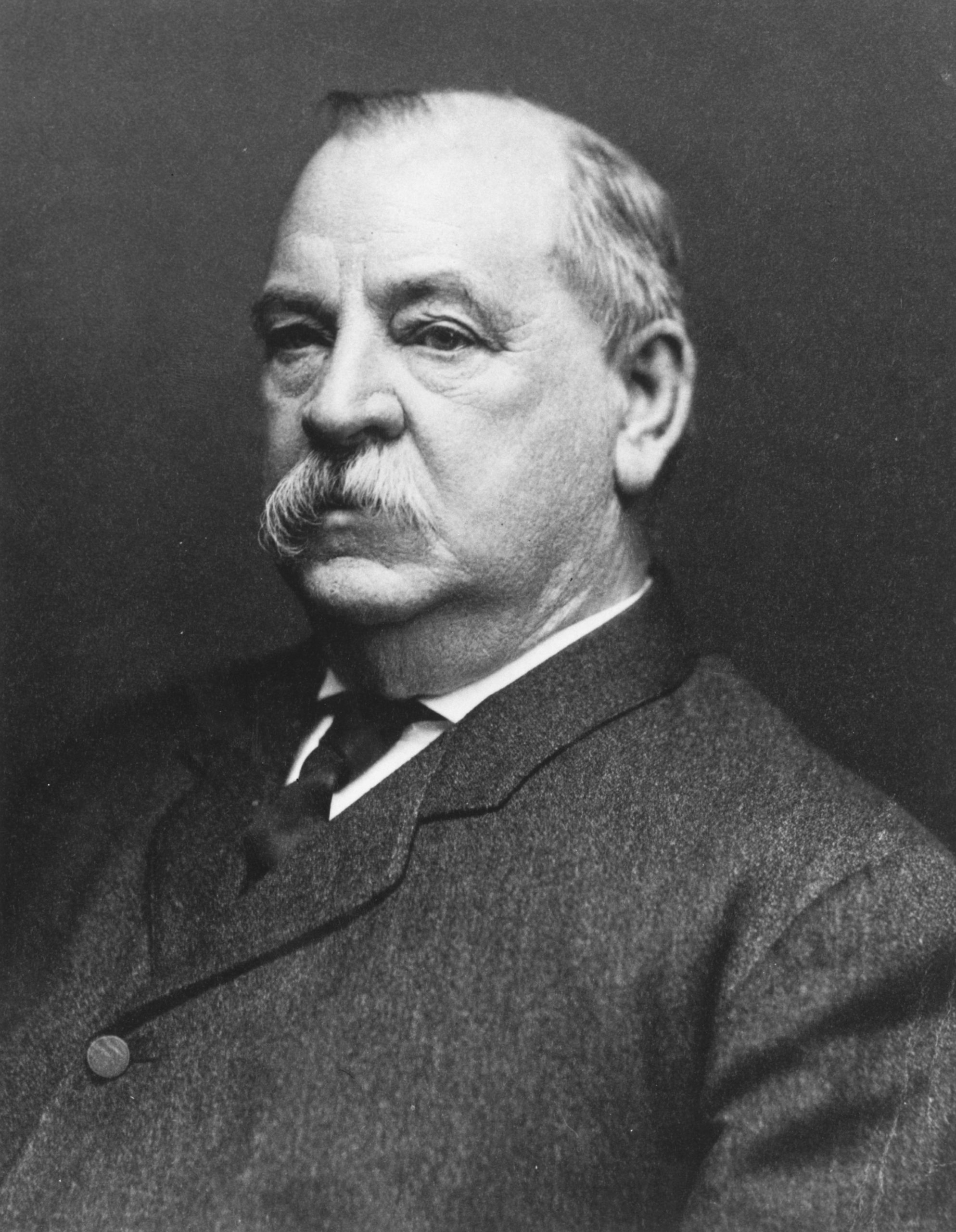

Excerpt from Ryan Walters, Grover Cleveland: The Last Jeffersonian President (Abbeville Institute Press, 2021)

While in his first term in the White House, Cleveland decided to make a symbolic gesture of goodwill toward the South. Acting on a recommendation from the secretary of war, the president decided to return captured Confederate battle flags to their respective Southern states. The move, though, provoked anger from the nation’s leading Union veterans group, the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.), which boasted a membership of 400,000 former troops. And with his promotion of former Confederates to high office, many Northerners were fearful that the South, through Cleveland, was attempting to re-establish Southern political dominance, the status it enjoyed before the war.

When the news broke of the flag order, Cleveland faced an avalanche of hateful invective from across the North. The New York Tribune called the flags “mementos of as foul a crime as any in human history.” Senator Joseph Hawley suggested they be burned instead, for they were nothing more than flags taken from “our misguided brothers and wicked conspirators.” Governor Joseph B. Foraker of Ohio used the issue in his re-election campaign, stating in a telegram: “No rebel flags will be surrendered while I am governor.”[i]

The commander of G.A.R., Lucius Fairchild, who lost an arm at Gettysburg, spoke harshly of the president. “May God palsy the hand that wrote the order! May God palsy the brain that conceived it, and may God palsy the tongue that dictated it!” General Sherman even privately hinted at his displeasure with the commander-in-chief. Writing to his brother, Senator John Sherman, he pointed out that “Mr. Cleveland is President, so recognized by Congress, Supreme Court, and the world” so he could not criticize him openly. But neither Cleveland nor Secretary of War Endicott could return the flags since they “never captured a flag” and “did not think of the blood and torture of battle.”[ii]

As the controversy persisted, things were becoming more heated by the day. The Grand Army’s national encampment that year was to be in St. Louis, Missouri, and the group had already invited the president to visit the camp and speak to the veterans. The city’s mayor also sent Cleveland an invitation. But after the flag flare up, the president received threats of violence from members of G.A.R., so he declined both the invitations. To the mayor he wrote that he was “hurt by the unworthy and wanton attacks upon me growing out of this matter, and the reckless manner in which my actions and motives have been misrepresented both publicly and privately,” as well as by the “threats of personal violence and harm” coming from “scores of misguided, unbalanced men.” Yet if the angered veterans at the national encampment wanted to “denounce me and my official acts,” he wrote, “I believe they should be permitted to do so, unrestrained by my presence as a guest of their organization, or as a guest of the hospitable city in which their meeting is held.”[iii]

The political heat arising from the flag issue became so great that President Cleveland was forced to quietly rescind the return order before the flags could be shipped south. The North, unlike the South, had still not gotten over the war. In 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt returned the flags without fanfare and with a unanimous vote by Congress, including many of those who had so vigorously opposed Cleveland’s order, demonstrating the opposition was more about politics than anything else.[iv]

As for the Grand Army of the Republic, which was as responsible as any group in the country for fomenting sectional hostility and hatred, Cleveland did not hold a high opinion of the organization, at least what he believed were the worst elements of it. The good that is in the organization, the president wrote in a private letter, “is often prostituted to the worst purposes.” It has been “played upon by demagogues for partisan purposes, and has yielded to insidious blandishments to such an extent that it is regarded by many good citizens … as an organization which has wandered a long way from its original design.” The group’s objectives, he believed, were “partisan, unjust, and selfish.”[v]

In the early fall of 1887, President Cleveland embarked on a trip that would take him through the Midwest and parts of the South, traveling to several major cities, including the original Confederate capital of Montgomery, and providing him the opportunity to speak before huge crowds that came from afar to see him and perhaps shake his hand. In Memphis, more than 100,000 Southerners traveled from several of the surrounding states to greet Cleveland. In Nashville, he visited the widow of President James K. Polk; in Atlanta, he dined with former Confederate general John B. Gordon. There was even talk of a movement to bring Jefferson Davis to Georgia to attend an event with Cleveland, but no such meeting ever took place, although the president, in a private letter, hinted that a meeting would not have been refused.[vi]

But in a move that might be seen as a revelation of his true feelings, when Melville Fuller, who Cleveland would appoint Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court in 1888, insisted the president visit Lincoln’s tomb as he passed through Illinois, Cleveland refused to do so. Whether his decision reflected his own thoughts, or was simply political pandering to his base in the South, tactics which Cleveland was never known to exhibit, we will never know, but throughout his tour of the South, President Cleveland never showed any feeling but genuine affection for Southerners as members of the American family.[vii]

Cleveland’s magnanimous attitude was also on display the year before when he traveled to Virginia and addressed citizens at the state fair in the former Confederate capital of Richmond. In his remarks, he praised the state and its rich, proud history, its traditions, its “true greatness,” and the “toil and ingenuity of her people.” The state, he told the crowd, was “the Mother of Presidents, seven of whose sons have filled that high office,” and on that day greeted “a President who for the first time meets Virginians upon Virginia soil.” He pledged to the people of Virginia, and of the entire South, that his administration “is pledged to return” for their hard work and ingenuity “not only promises, but actual tenders of fairness and justice, with equal protection and a full participation in national achievements.” The past, he said, is where the relationship between North and South had been “estranged and … interrupted,” but “your enthusiastic welcome” of the president “demonstrates that there is an end to such estrangement, and that the time of suspicion and fear is succeeded by an era of faith and confidence.”[viii]

And his affection for the South and Southerners did not exclude honoring the former Confederacy and its military heroes. In the spring of 1887, Confederate veterans in the Association of the Army of Tennessee invited Cleveland to the battlefield at Shiloh to attend the unveiling of a statue of General Albert Sidney Johnston, killed there twenty-five years before. The president’s official duties prevented him from making the trip but he did send a gracious letter praising Johnston for his “conspicuous valor,” “military ability,” and for exhibiting the “highest personal character,” Cleveland wrote. Every citizen of the country should take pride in the character of General Johnston, the president believed. Southerners had not heard such gracious words from a president in a generation.[ix]

Yet it must be noted that Cleveland’s affection for Southerners included both races. Racial issues were always a hot-button topic, even in Cleveland’s day, and the South was the region most affected since the vast majority of blacks in America lived below the Mason-Dixon Line. As a nineteenth century white man, and given the prevailing attitudes of the day, Grover Cleveland did not interfere with the “Jim Crow” system of segregation prevalent in the South, nor did any other president for that matter. But the system was also dominant in the North. In fact, in his epic book The Strange Career of Jim Crow, C. Vann Woodward points out that the system of segregation, though generally blamed on the South, “was born in the North and reached an advanced age before moving South in force.” Northerners “made sure in numerous ways that the Negro understood his ‘place’ and that he was severely confined to it.” Both political parties in the North, Democrats and Republicans alike, “vied with each other in their devotion” to white supremacy. “It is clear,” concludes Woodward, “that when its victory was complete and the time came, the North was not in the best possible position to instruct the South, either by precedent and example, or by force of conviction, on the implementation of what eventually became one of the professed war aims of the Union cause – racial equality.”[x]

According to scholar John Chodes, systematic segregation came not as a result of Southern racism but government policy, and at a time when Northerners exclusively ran Washington. Segregation “is the result of federal policy from 1865 to 1900 to divide the white and black races and to promote discord and hatred for political advantage.” They accomplished this during Reconstruction via the Union League, the Freedman’s Bureau, the Bureau of Education, and various congressional acts.[xi]

In his only brush with segregation as a policy, Cleveland, as governor of New York, signed a bill that would “retain the colored schools separate and distinct from the whites” in New York City. The bill’s intent was to block the New York City public schools from consolidating the black and white schools and Governor Cleveland approved it when it was “strongly urged before me that separate schools were of much more benefit to the colored people than mixed schools.” In fact, the superintendent of the black schools in the city wanted to keep the segregated arrangement. So Cleveland was only perpetuating a system that had a long history in his section of the country decades before he became governor and president.[xii]

But in other areas involving race, Cleveland was a little ahead of his time and has been considered by most a racial moderate. He did not hold obsessive racist thoughts and did as much he could for the plight of black Americans. While some historians have condemned Cleveland as being a typical racist president who gave no place to blacks either in the White House or in his administration, those notions are plain wrong. He named a black man, Winston Sinclair, as White House steward, with the responsibility for supervising the property and the grounds around the executive mansion, which was an important job. As president, wrote Clarence Lusane, author of The Black History of the White House, Cleveland “represented a transitional moment in the relationship between African Americans and the White House, and African Americans and the nation.” Nearly all of Cleveland’s biographers, even some of his most sympathetic, overlook these facts.[xiii]

In 1887, Cleveland replaced Frederick Douglass, a Republican serving as Recorder of Deeds for Washington, D.C., the highest-ranking African American in the country, with another black man, James Monroe Trotter of Mississippi, who had escaped slavery to Ohio via the Underground Railroad. Douglass, who had met with the president on several occasions, wrote fondly of Cleveland in his memoirs. “I have no cause of complaint against him” for the removal, wrote Douglass, while “there is much for which I have reason to commend him. I found him a robust, manly man, one having the courage to act upon his convictions, and to bear with equanimity the reproaches of those who differed from him. He never failed while I held the office under him, to invite myself and wife to his grand receptions, and we never failed to attend them.” And Cleveland was not “less cordial and courteous than that extended to the other ladies and gentlemen present,” he wrote, and “he was too noble to refuse me the recognition and hospitalities that my official position gave me the right to claim.”[xiv]

Cleveland also greatly admired Booker T. Washington, black leader and founder of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, who also had great admiration and respect for the president. Washington had given a tremendous speech at the Atlanta Cotton Exposition in the fall of 1895 and he sent a copy to Cleveland, which greatly impressed the president. “Your words cannot fail to delight and encourage all who wish well for your race,” he wrote to Washington in a letter of thanks. Because of “your utterances,” American blacks should “gather new hope and form new determinations to gain every valuable advantage offered them by their citizenship.”[xv]

“From that time until the present,” wrote Washington in his memoirs, Up From Slavery, “Mr. Cleveland has taken the deepest interest in Tuskegee and has been among my warmest and most helpful friends.” The president has “shown his friendship for me in many personal ways, but has always consented to do anything I have asked of him for our school.” Cleveland gave personal donations and used his “influence in securing the donations of others.” Washington did not believe Cleveland “is conscious of possessing any colour prejudice. He is too great for that.”[xvi]

When Cleveland, along with his Cabinet, visited the Expo, he met personally with Washington, who “became impressed with his simplicity, greatness, and rugged honesty.” Having the opportunity to meet Cleveland on future occasions, Washington wrote that “the more I see of him the more I admire him.” Along with Washington, Cleveland “spent an hour in the Negro Building, for the purpose of inspecting the Negro exhibit and of giving the coloured people in attendance as opportunity to shake hands with him.” The president “seemed to give himself up wholly, for that hour, to the coloured people. He seemed to be as careful to shake hands with some old coloured ‘auntie’ clad partially in rags, and to take as much pleasure in doing so, as if he were greeting some millionaire.” He also signed an autograph for everyone who sought it.[xvii]

For Grover Cleveland, as it was for Booker T. Washington, the goal was to bring blacks, many of them less than a generation removed from slavery, into the fullness of American society. Just as Cleveland believed with Native Americans, the government should work to assimilate blacks completely into civilization. And the best way to do that for black people, he felt, was through educational opportunities. In fact, Cleveland referred to black education as “the proper solution of the race question in the South.” The efforts of Booker T. Washington and the Tuskegee Institute “point the way to a safe and beneficent solution.” If blacks “in their mature years” are to “exercise … the right of citizenship,” he wrote in a private letter, “they should be fitted to perform their duties intelligently and thoroughly.” To this effort, Cleveland contributed not just rhetoric but financial contributions as well.[xviii]

Throughout his time in public office, Grover Cleveland took Jeffersonian principles to heart, most particularly the notion of “equal and exact justice to all men,” regardless of who they were. The days of slavery were long gone; the days of warfare between the states were likewise over. It was time for North and South to reconcile and move forward as one nation and he saw himself as one who could begin the process of reconciliation and reunion, despite the pressures from those who would not let go of a disagreeable past.

*************

[i] John M. Taylor, “Grover Cleveland and the Rebel Banners,” Civil War Times Illustrated, September 1994.

[ii] Jack Beatty, Age of Betrayal: The Triumph of Money in America, 1865-1900 (New York: Vintage Books, 2008), xiii; William T. Sherman to John Sherman, June 26, 1887, The Sherman Letters: Correspondence Between General and Senator Sherman from 1837 to 1891, edited by Rachel Sherman Thorndike (London, 1894), 375.

[iii] Cleveland to the Mayor of St. Louis, MO, July 4, 1887, Parker, Writings and Speeches, 398-401.

[iv] John M. Taylor, “Grover Cleveland and the Rebel Banners,” Civil War Times Illustrated, September 1994.

[v] Cleveland to E. W. Fosnot, October 24, 1887, Nevins, Letters, 160.

[vi] Nevins, Cleveland, 319-320; Brodsky, 197-198.

[vii] Cleveland to Wilson S. Bissell, September 2, 1887, Nevins, Letters, 149-151.

[viii] Cleveland, Speech at the Virginia State Fair, October 12, 1886, Parker, Writings and Speeches, 159-160.

[ix] Cleveland to Walter H. Rogers, April 1, 1887, Nevins, Letters, 132-133.[x] C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow (Oxford, 1955), 17-18, 20.

[xi] John Chodes, Segregation: Federal Policy or Racism? (Columbia, SC: Shotwell Publishing, 2017), 6.

[xii] Cleveland to G. A. Sullivan, August 27, 1887, Nevins, Letters, 149.

[xiii] Kenneth T. Walsh, Family of Freedom: Presidents and African Americans in the White House (Boulder, Co, 2011), 8; Clarence Lusane, The Black History of the White House (San Francisco, 2011), 241.[xiv] Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, in The Frederick Douglass Papers, edited by John R. McKivigan, Series Two, Volume 3, Book 1 (New Haven, Yale University Press, 2012), 391-392.

[xv] Raymond W. Smock, Booker T. Washington: Black Leadership in the Age of Jim Crow (Chicago, 2009), 161; Cleveland to Booker T. Washington, October 6, 1895, in Booker T. Washington, Up From Slavery (New York, 1907), 227.

[xvi] Booker T. Washington, The Story of My Life and Work (New York, 1901), 156; Cleveland to Washington, Up From Slavery, 228.

[xvii] Washington, Up From Slavery, 227-228.

[xviii] Cleveland to Isaiah T. Montgomery, January 14, 1891, Parker, Writings and Speeches, 344-345; Cleveland, Speech to the Southern Educational Association, April 14, 1903, Bergh, 423-425.

To All Black Business News:

I have read your list of presidents that should have been indicted BEFORE Trump. Quite an impressive list, indeed! A very impressive bit of presentism, also. But you left out one important slave holding president – Abraham Lincoln. Mary Todd, wife of old Abe, inherited from her father several slaves and since the law at the time did not recognize that women could own property in their own right, ownership devolved to her husband, in this case, Honest Abe. That made him a slave owner and in the absence of any manumission papers and no further mention s made of them, it can be assumed that he sold those slaves and pocketed the proceeds, making him a slave dealer/trader as well.

If that doesn’t burst your bubble, it should.