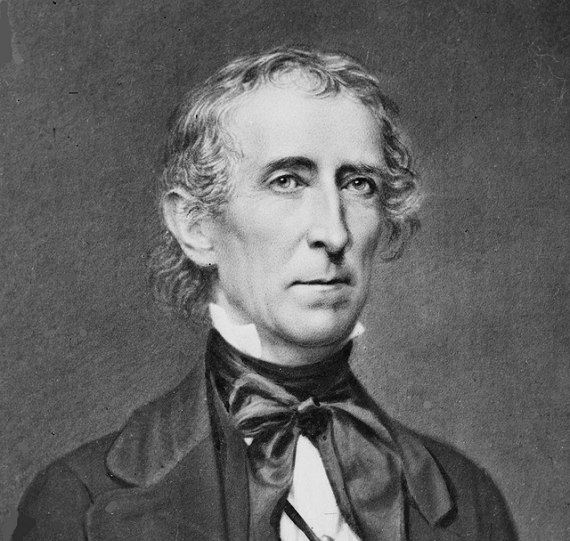

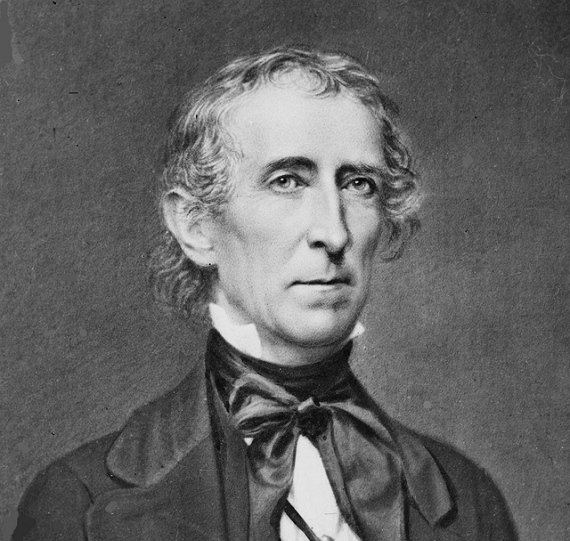

In honor of John Tyler’s birthday (March 29), I thought it proper to include a excerpt from my new book, Compact of the Republic: The League of States and the Constitution, detailing the actions of a President I believe followed the Constitution strictly and has been cast aside by history. Called “His Accidency” by his political adversaries to refer to the way in which he assumed the office, John Tyler is perhaps the most underrated President in United States history.

During his term in office, John Tyler was sometimes considered to be more of a Jeffersonian than that of Thomas Jefferson himself. This is meant to suggest that he carried out his ideological and political life in a constitutional fashion even more strictly than Jefferson. Tyler condemned Andrew Jackson’s threat of force in the matter of the Force Bill that passed Congress and was signed by Jackson in 1833. He made a famous speech in support of South Carolina in 1833 and attacked Jackson’s policy. Historian Douglas Southhall Freeman called Tyler “an ideal of political consistency in an era of change.”[1] Freeman elaborated, noting that Tyler “was not a man to regard himself as the custodian of a tradition, but he was a man to adhere with singular tenacity to that tradition.”[2]

Tyler was loathed by his political adversaries, especially during his presidency. Former Mayor of New York Philip Hone wrote in 1842 that “one year of the rule of imbecility, arrogance, and prejudice has taught them the folly of selecting for Vice-President a man of whose fitness for the office of President they had no reasonable assurance.”[3] In a time where Whigs were the driving political force in Washington, strident toward massive unconstitutional measures, Tyler held his ground and character despite all falsehoods told about him and all misrepresentations attributed to him.

Like Jefferson, Tyler had a purely compact view of the United States constitution and recognized that state governments had not yielded power to do all things whatsoever to the federal government. Because of this, he never complied with the obviously unconstitutional legislation that was placed before him. Tyler consistently ranks at the bottom of “best President” polls, but he did much to perpetuate the cause that his fellow Virginian did in his only presidential term. Tyler was continually mocked and ridiculed by the Whig forces that controlled the Congress in his day for his strict adherence to the Constitution.

Tyler was elected as William Henry Harrison’s running mate in 1840, but Harrison died only one month into his term making Tyler the first Vice-President to assume the duties of president. In his first presidential address, Tyler urged that those in the general government should “carefully abstain from all attempts to enlarge the range of powers thus granted to the several departments of the Government other than by an appeal to the people for additional grants.”[4] By doing so, Tyler said, would “disturb that balance which the patriots and statesmen who framed the Constitution designed to establish between the Federal Government and the States composing the Union.”[5] Tyler’s actions as President would mirror his words.

The presidential oath he took had been considered controversial at the time, because there hadn’t been a consensus about who becomes President if the sitting President dies while in office. It can be surmised, however, that the assertions against Tyler’s claim to the presidency were based on political grounds rather than on constitutional premises. The Constitution states, “In Case of the Removal of the President from Office, or of his Death, Resignation, or Inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office, the Same shall devolve on the Vice President.“[6] Since the same powers and duties would be inherited by the Vice President, including the “executive Power” noted in the vestment clause that would be given to a “President of the United States of America,”[7] it seems as if Tyler’s Whig opponents were attempting to take advantage of the situation. The actions of Tyler in assuming the presidency were met with considerable scorn by the Whigs.

In his first meeting of Harrison’s former cabinet, Tyler was expected by the cabinet to continue Harrison’s policy of making decisions based on cabinet majority vote. To this, Tyler responded:

“I beg your pardon, gentlemen; I am very glad to have in my Cabinet such able statesmen as you have proved yourselves to be. And I shall be pleased to avail myself of your counsel and advice. But I can never consent to being dictated to as to what I shall or shall not do. I, as President, shall be responsible for my administration. I hope to have your hearty co-operation in carrying out its measures. So long as you see fit to do this, I shall be glad to have you with me. When you think otherwise, your resignations will be accepted.”[8]

Daniel Webster was especially disturbed at Tyler’s arrangements, and eventually resigned. The Whigs tried to resurrect the idea of a new national bank several times, all of which were met with presidential veto. They were bolstered in their efforts by the supposition that the Panic of 1837 would have been prevented if there had been a national bank. In reality, British demand for cotton fell drastically while at the same time demanding hard currency for new exports, which caused a stagnation of capital flow from England to the United States.[9] Tyler had the same kind of qualms toward the bank as Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson did, i.e. that it would be an instrument to shackle and subjugate subsequent generations and stole property from the current one, and was wholly unconstitutional. Henry Clay made two attempts to institute a new national bank, using the Panic of 1837 as political capital. Opponents of Tyler’s view explained that the bank was “approved by some of the most competent financiers of this country and of England, and pronounced to be adequate to all our wants, safe in its operations, and calculated to furnish the most perfect currency that could be devised.”[10] Tyler vetoed both endeavors of Clay to institute the bank. A primary reason for the bank veto was that it violated Tyler’s state’s rights conscience.[11] Tyler, like Jefferson, waged a political war over the creation of a national bank, on constitutional grounds which respected the compact view of limited powers.

Before he was President, Tyler as a Senator opposed the Force Bill referenced earlier, which would authorize the President to use military prowess to enforce the so-called Tariff of Abominations. Tyler stood strongly against this measure, believing it to be a method of coercion, one not consistent with the occasion of the states entering into the union. Tyler ended up being the only Senator in Congress to vote against the Force Bill. Tyler, referring to South Carolina, wrote, “But I will not join in the denunciations which have been so loudly thundered against her, nor will I deny she has much cause of complaint.”[12] Tyler considered that Jackson’s Proclamation provocation had “swept away the barriers of the Constitution and given us in place of the Federal government, under which we had fondly believed we were living, a consolidated military despotism.”[13] Tyler’s thoughts and actions were the direct results of his constitutional views, and precisely what one would expect of a firm believer in state’s rights.[14]

As President, Tyler regularly vetoed all bills he believed to be built upon unconstitutional ground. Despite political pressures inclined toward the necessity of government revenue, Tyler vetoed a provisional tariff despite widespread popular appeal. After the veto, an attempt was made to pass a similar permanent tariff. Tyler again vetoed the second attempt to raise the tariff rate above the twenty percent level of tradition through the prior decade. Tyler, in contrast, wanted to stay within the twenty percent rate created by the Compromise Tariff of 1833, which was recognized as a resolution to the Nullification Crisis explained earlier. Tyler recognized the need for government revenue, but still would not falter in his aims to keep the tariff moderate. Tyler explained his actions,:

“While the Treasury is in a state of extreme embarrassment, requiring every dollar which it can make available, and when the government has not only to lay additional taxes, but to borrow money to meet pressing demands, the bill proposes to give away a fruitful source of revenue…a proceeding which I must regard as highly impolitic, if not unconstitutional.”[15]

Tyler wanted to retire the high debt of the general government while not raising the tariff to extreme levels. Like Jefferson, Tyler was an enemy of public debt. According Tyler biographer Oliver Chitwood, this decision was certainly another cause for friction between the executive and legislative branches of the government and served as an occasion for widening the rift in the Whig Party, of which Tyler was still a part of.[16] Any view that Tyler could be guided by the whims of compromise would be exhausted by his actions.

Tyler’s actions burned any remaining bridges between he and his party, and the Whigs in Congress officially expelled him from their party. To use a term coined by Henry Clay, Tyler became “a President without a party.”[17] Tyler finished his presidential term as a man without a party. Even in his own time, he was mocked as “His Accidency.” Whigs in Congress also attempted to impeach Tyler, in the first proceedings against a President in American history. Tyler stood defiant, sending a protest to the House. Tyler wrote,

“I am charged with violating pledges with I never gave…usurping powers not conferred by the law, and above all, with using the powers conferred upon the President by the Constitution from corrupt motivates and for unwarrantable ends.”[18]

Ironically, Tyler usurped no powers, realizing that it was actually Congress which constantly encouraged him to take extra-constitutional measures which weren’t delegated to that of the executive in the Constitution. If anything, the Whig Congress attempted to usurp powers not conferred to that branch by the Constitution, something Tyler openly observed. Their attempts to do so fell on deaf ears, as Tyler was a unique champion of the Constitution. Tyler could never be what the Whigs wanted him to be in his foundation of the powers of the general government. He believed that they had to take him for what he was, rather than allow himself to be swayed toward political expedience. Tyler respected the establishment of the constitutional compact to which the states consented, and had a particular grasp of the Constitution shared by few other Presidents in United States History. Tyler implemented its ideals into his Presidency despite powerful detractors. For his insistence and stubborn principles, Tyler should be considered a heroic President, not a forgotten one.

References:

[1] Oliver Chitwood, John Tyler: Champion of the Old South (Newtown: American Political Biography, 2006), vii (Forward).[2] Ibid, viii (Forward).

[3] Philip Hone, The Diary of Philip Hone 1828-1851 Volume One (New York: Cornell University, 1889), 123.

[4] John Tyler, Address Upon Assuming the Office of the President of the United States, April 9, 1841, accessed September 10, 2013; available at http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=533

[5] Ibid.

[6] This clause is located in Article II, Section 1 of the United States Constitution. The full clause reads, “In Case of the Removal of the President from Office, or of his Death, Resignation, or Inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office, the Same shall devolve on the Vice President, and the Congress may by Law provide for the Case of Removal, Death, Resignation or Inability, both of the President and Vice President, declaring what Officer shall then act as President, and such Officer shall act accordingly, until the Disability be removed, or a President shall be elected.”

[7] This appears in Article II, Section 1 of the United States Constitution, sometimes called the “vestment clause.” The relevant text reads, “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.”

[8] Oliver Chitwood, John Tyler: Champion of the Old South, 270.

[9] Peter Temin, The Jacksonian Economy (New York: W.W. Norton, 1969), 88.

[10] Oliver Chitwood, John Tyler: Champion of the Old South, 292.

[11] Ibid, 267.

[12] Ibid, 115.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid, 114.

[15] Ibid, 299.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid, 317.

[18] Ibid, 301-302.