The introduction to Mike Church’s edited volume of Albert Taylor Bledsoe’s masterful work, Is Davis A Traitor? or Was Secession a Constitutional Right Previous to the War of 1861?

The Congress of the Confederate States of America adopted “Deo Vindice” (God Will Vindicate) as the official motto of the Confederacy in 1864. Less than a year later, Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia, President Jefferson Davis and his cabinet fled Richmond, the Confederate Congress folded, the Confederate Constitution became a relic rather than a framework of government, and tearstains mixed with blood on tattered and muddied butternut. Despair, defeat, destruction, and destitution marked the hour. God, it seemed, had abandoned the Confederacy in its time of need. Yet, though the cause of independence was lost, vindication for the principle of secession and for the Southern people still seemed possible, if faint.

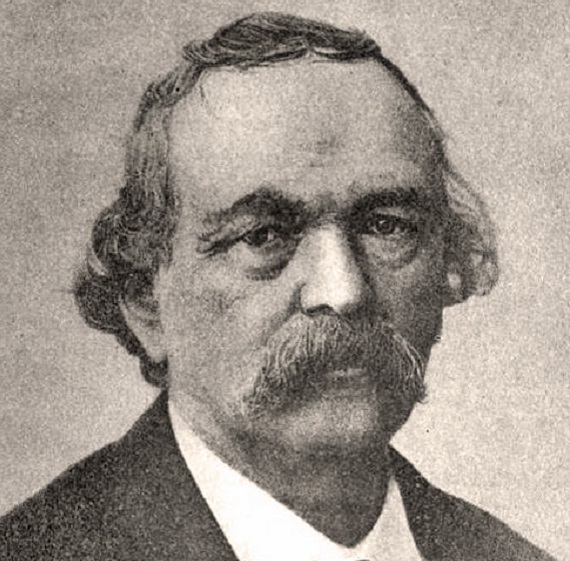

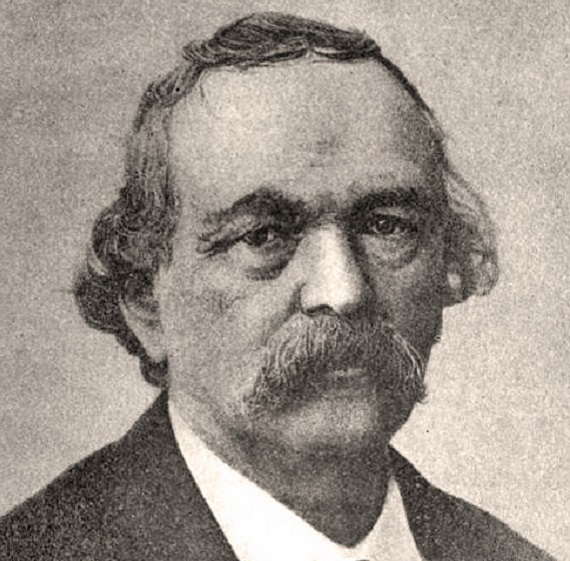

In the years after the War, several Confederate leaders put down their swords and picked up their pens in an attempt to salvage this “Lost Cause.” To the North, these men were traitors, rebels, and devils, participants in a “wicked rebellion.” But to Southerners, they were heroes and patriots following the principles of 1776. Their cause had been that of Washington and Jefferson, of Kings Mountain, Cowpens, and Yorktown. Both Jefferson Davis and Confederate Vice-President Alexander H. Stephens wrote brilliant multi-volume works in defense of the Confederacy; newspaperman Edward Pollard coined the term the “Lost Cause” with the publication of a blistering defense secession and the Southern people by the same title; classical scholar Basil L. Gildersleeve reinforced Southern honor and chivalry in his Creed of the Old South; and educator Jabez L.M. Curry published an impenetrable defense of Southern contributions to American civilization. All were well received by the Southern public, but the first and best defense of secession in the postbellum era dripped from the pen of the eccentric scholar and lawyer, native Kentuckian Albert Taylor Bledoe. In fact, Lee reportedly remarked to Bledsoe in 1865, “Doctor, you must take care of yourself; you have a great work to do; we shall look upon you for our vindication.” It appeared the future fate of secession in principle rested upon his shoulders. No man was better for the task.

Bledsoe was born in Kentucky in 1809, the son of Moses Owsley Bledsoe—a noted Whig newspaper editor—and Sophia Childress Taylor from the famous Taylor family of Virginia, a line which included President Zachary Taylor. He entered West Point in 1826 at the age of fifteen with little formal education and moved from the bottom to the top of the class in his four years at the Academy. He finished second in his class in mathematics and claimed that he would have been first had not another cadet entered he institution with more studies in that area. He became an avid student of moral philosophy and though French precluded him from entering West Point in 1825, Bledsoe became fluent in the language and translated several mathematic textbooks from French to English after he was graduated.

His time at West Point coincided with several Southerners who became both close friends and conspicuous participants in the tumultuous events of the 1850s and 1860s, including Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, Albert S. Johnston, Joseph E. Johnston, and Leonidas Polk. Davis and Bledsoe corresponded frequently, particularly late in life, and Polk was not only Bledsoe’s roommate at West Point and his closest friend, he, along with Episcopal minister Charles P. McIlvaine, was most responsible for Bledsoe’s spiritual awakening. Bledsoe first took communion in 1826 and became a devout Christian.

Bledsoe served his mandatory two years at Fort Gibson in present Oklahoma after his graduation in 1830, but military life did not suit him. He moved to Richmond, Virginia and studied law under the direction of his uncle, but left in 1833 to take a job as an adjunct instructor in mathematics and French at Kenyon College in Ohio. Reverend McIlvaine had recently been appointed president of the college and he personally invited Bledsoe to teach. Bledsoe entered the seminary at Kenyon in 1834 and took orders in the Episcopal Church in 1836. He also met his future wife, Harriet Coxe, there in 1835.

He spent several years in the ministry around Ohio and Kentucky, but he described this period of his life as miserable. He was forced to resign a teaching position at Miami College in Ohio after a dispute with the administration, quarreled with Church leaders in Ohio over theological interpretation, and became physically ill and financially destitute by 1839. He moved to Springfield, Illinois in 1839 to reunite with his family, was admitted to the Illinois bar in 1839, and by 1840 had formed a successful law partnership with one of Abraham Lincoln’s political allies, Edward Baker a notorious political thug who helped propel Lincoln to the highest echelon of the Republican Party.

For the next eight years, Bledsoe practiced law in Springfield, wrote a work of theology, and found an interest in politics. He also became intimately acquainted with “Honest Old Abe” Lincoln, himself a lawyer of great repute in Springfield (Lincoln owned a large home across the street from the capital). The two had stood shoulder to shoulder as Whigs during the 1840s by appearing on the same stage in various political contests, and Bledsoe won more than he lost against Lincoln as an attorney. He even trained Lincoln in the use of a broadsword when Lincoln was once challenged to a duel. Bledsoe wrote after the War that he believed Lincoln to be an intelligent though mysterious figure with a vulgar personality marked by laziness, immorality, Godlessness, and a lust for popularity. Bledsoe’s most recent biographer concludes this was a result of the lingering bitterness of defeat, but that would make Bledsoe dishonest and spiteful, two character foils he did not possess.

Bledsoe returned to the academy in 1848 at the newly established University of Mississippi as the chair of the mathematics and astronomy department. Ole Miss had several noteworthy administrators and faculty at its founding. The Chancellor at the time was Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, famed Methodist minister, educator, author, newspaper editor, staunch Jeffersonian, and uncle and mentor of Confederate General James Longstreet, and Bledsoe’s assistant was Lucius Q.C. Lamar, Confederate Minister to Russia, United States Congressman and Senator, Secretary of the Interior during the Grover Cleveland administration, and Justice of the Supreme Court. In 1854, Bledsoe accepted the position of chair of the mathematics department at the University of Virginia—the finest institution in the South at the time—and remained there until the start of the War in 1861.

Doubtless, his time in the South during this period impacted his political views. He abandoned his early support for the Whig Party and recoiled at the dramatic political changes of the 1850s, most importantly the rampant demagoguery of Northern politicians and the fanaticism of Northern abolitionists. As the South came under attack, Bledsoe, like other Southern authors and intellectuals, defended her with vigor. His Essay on Liberty and Slavery was well received, though it was more moderate than other works on the subject. When the War began in 1861, Bledsoe joined the Confederate Army as a colonel and was appointed to the War Department. He despised administrative work and bristled at its bureaucratic constraints. He resigned in 1862 and briefly returned to the University of Virginia, but both Jefferson Davis and Bledsoe himself believed he could still help the Confederacy as an intellectual advocate for independence and secession, not at home, but in Europe.

Bledsoe had a completed manuscript ready to publish in 1862 entitled “Fall of the American Union,” a portion of which appeared in the Army and Navy Messenger in 1863. Slavery, Bledsoe concluded, was not the root of Southern independence. The differences between the North and South were “as deep as the foundations of society itself, and as universal as the interests of humanity.” The protagonists in this bloody struggle were Northern politicians determined to “fall back on the dogma of the most absolute equality of men, as the best means to weaken and humble the South, as well as to unite all her own citizens, whether native or foreign, in opposition and hatred of the small section….” and Southern leaders resolved not to fall into the “dark abyss of radicalism.” The War was the result of a political conflict forged from the earliest days of the federal republic between the nationalists and the republicans. By 1861, the South stood like the Spartans at Thermopylae in 480 B.C., ready to die rather than be overwhelmed by Northern despotism. This was the book both Davis and Bledsoe hoped would sway public opinion in London toward the Confederate cause.

In 1863, Bledsoe ran the blockade and arrived in London as an unofficial representative of the South, a partisan working to shore up European support and potentially help bring needed diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy. He had the backing of Englishman James Spence, author of the pro-secession work The American Union, and several other well-connected newspapermen. Bledsoe worked quickly and diligently, and his essays appeared in two major London newspapers during the War. He spent hours in the British Museum researching for what would later become his magnum opus, Is Davis a Traitor? His work as an essayist in London sharpened his arguments, and when the War ended in 1865, Bledsoe left England with an almost completed two-volume manuscript on the justification of secession, one that he confidently claimed “completely refuted all [Northern] sophism, and vindicated the cause of the South.”

He arrived back in Virginia in 1866, took the oath of allegiance to the United States and proceeded to plan for the publication of his “labor of love.” At the time, Jefferson Davis was incarcerated at Fortress Monroe in Hampton, Virginia, held for treason against the United States since 1865. His health suffered and his trial would be delayed several times over a two year period and then never happened, but by 1866, security was fairly lax. Bledsoe was permitted to spend the day with Davis in private in August 1866. Davis insisted that Bledsoe publish his “little work on secession” immediately. Bledsoe reassured Davis that it would be in print that fall, and he hoped that his work would serve to “vindicate a cause so noble and so just….”

Is Davis a Traitor; Or Was Secession a Constitutional Right Previous to the War of 1861? was published in Baltimore in either September or October 1866. Bledsoe’s style is sharp, his wit superb, and his grasp of the historical arguments for secession and State power unsurpassed. He concentrated his attack on the three-headed intellectual hydra of nationalism in the antebellum period, Daniel Webster, Joseph Story, and John Motley, and their political master Abraham Lincoln. Each blow from his ink drenched sword chipped away at their supposed infallible and impenetrable reputations and arguments. Webster and Story were exposed as nothing less than duplicitous sophists and Lincoln as a partisan fool duped by the irresponsible positions of his nationalist heroes. He used their words against them and referenced both Madison’s notes of the Philadelphia Convention and other published works of the ratification period to prove that the Constitution was ratified in 1788 as a compact between States, that an “American people” did not and could not exist, and that secession, the opposite of accession, was an implied condition of ratification at the time.

Almost immediately after publishing Is Davis a Traitor?, Bledsoe established the Southern Review in Baltimore. With the help of his daughter, Sophia Bledsoe Herrick, he operated the magazine until his death in 1877, though it never made much money. He wrote most of the essays himself, and he continued through book reviews, philosophical and theological ruminations, and editorial critique to promote the principles of secession, the spirit of the Southern people, and the justness of the Southern cause. His was a one man crusade for Southern honor and the truth regarding the Constitution and the federal Union of the founding generation.

Is Davis a Traitor? is not simply a defense of the “Lost Cause,” it is a fine commentary on the Constitution matched only by St. George Tucker’s View of the Constitution of the United States and Abel P. Upshur’s A Brief Enquiry into the Nature and Character of Our Federal Government in the antebellum period. Every serious student of the Constitution should read it, for as Bledsoe suggested in his introduction, Southerners in 1861 were “perfectly loyal to truth, justice, and the Constitution of 1787 as it came from the hands of the fathers.” They were Americans—not traitors—operating under a belief that the right of secession was the essential principle of the American tradition. No one who understands the Constitution as ratified in 1788 could argue against that point.

One Comment