Families in the South connect in complicated ways. James Dickey [1923-1997] was the famous author of the 1970 novel, Deliverance, about 4 Atlanta men who take canoes down a north Georgia river and become violently entangle with the local mountain men. James Dickey himself appears at the end of the movie version (1972) in the character of the Sheriff, with a deep Southern drawl, trying to untangle the unexpected deaths. As a poet, Dickey had no superior in his generation. He was appointed the 18th United States Poet Laureate in 1966, and received the Order of the South award. He spent his last 28 years in academia at the University of South Carolina in Columbia.

Born and raised in Atlanta, Dickey briefly attended Clemson, then served in the Air Force in World War Two and in the Korean War, logging 500 combat hours. Between the wars, he attended Vanderbilt University, earning a B.A. in English and Philosophy in 1959 and an M. A. in English in 1960. He then worked for a time in advertising in Atlanta on the Coca-Cola and Lay’s potato chip accounts, which is where the story intersects with the Holbrook family (my paternal grandmother’s family) who were concentrated in Forsyth County, Georgia, just north of Atlanta.

Miss Charlotte Holbrook was the youngest of 16 children of her father, Parks Bell Holbrook, and the 13th and last child of her mother, formerly Aurora Viola Hardman. Charlotte was born in 1923, just after her father died. She had a charming personality and was married, in 1936, to William (Bill) Watt Neal of Atlanta. My grandfather, Dr. Stewart R. Roberts, her brother-in-law, gave her in marriage. Bill Neal established an advertising firm, known as Liller Neal, and for a period of time, employed James Dickey who later said, “I was selling my soul to the devil all day….and trying to buy it back at night.”

James Dickey published 53 poems in The New Yorker from 1959 to 1998. In the October 12, 1963 issue, his poem, Cherrylog Road appeared. In that version, a certain “Charlotte Holbrook” is named 3 times in this poem in which the author waits inside a junkyard car for her to appear (“Off Highway 106 / At Cherrylog Road I entered / The ’34 Ford without wheels, / Smothered in kudzu……….Where I sat in the ripped back seat / Talking over the interphone / Praying for Charlotte Holbrook / To come from her father’s farm”). “Charlotte Holbrook” arrives and, after the intense rendezvous, leaves “by separate doors / Into the changed other bodies / Of cars, she down Cherrylog Road / and I to my motorcycle….”

In a 1964 review of James Dickey’s book of poems, Helmets, Wendell Berry wrote, “’Cherrylog Road’ is a funny, poignant, garrulous poem about making love in a junk yard. It surely owes a great deal to the country art of storytelling. It’s a poem you want to read out loud to somebody else, and it’s best and most enjoyable when you do.”

At the request of Bill Neal, the husband of Charlotte Holbrook, James Dickey apparently agreed to replace the name, “Charlotte,” in all subsequent versions of selected and collected poetry editions. The name “Doris” Holbrook was used thereafter. But the story ends more positively. Bill and Charlotte Neal had a daughter, Pauline (“Polly”), who married Albert Boyd Braselton, who worked also in the advertising firm, Liller Neal. In 1970, James Dickey dedicated his novel, Deliverance, to Al Braselton, the son-in-law of Charlotte Holbrook Neal, so if any discord had occurred 7 years earlier, perhaps it was minimal and transient.

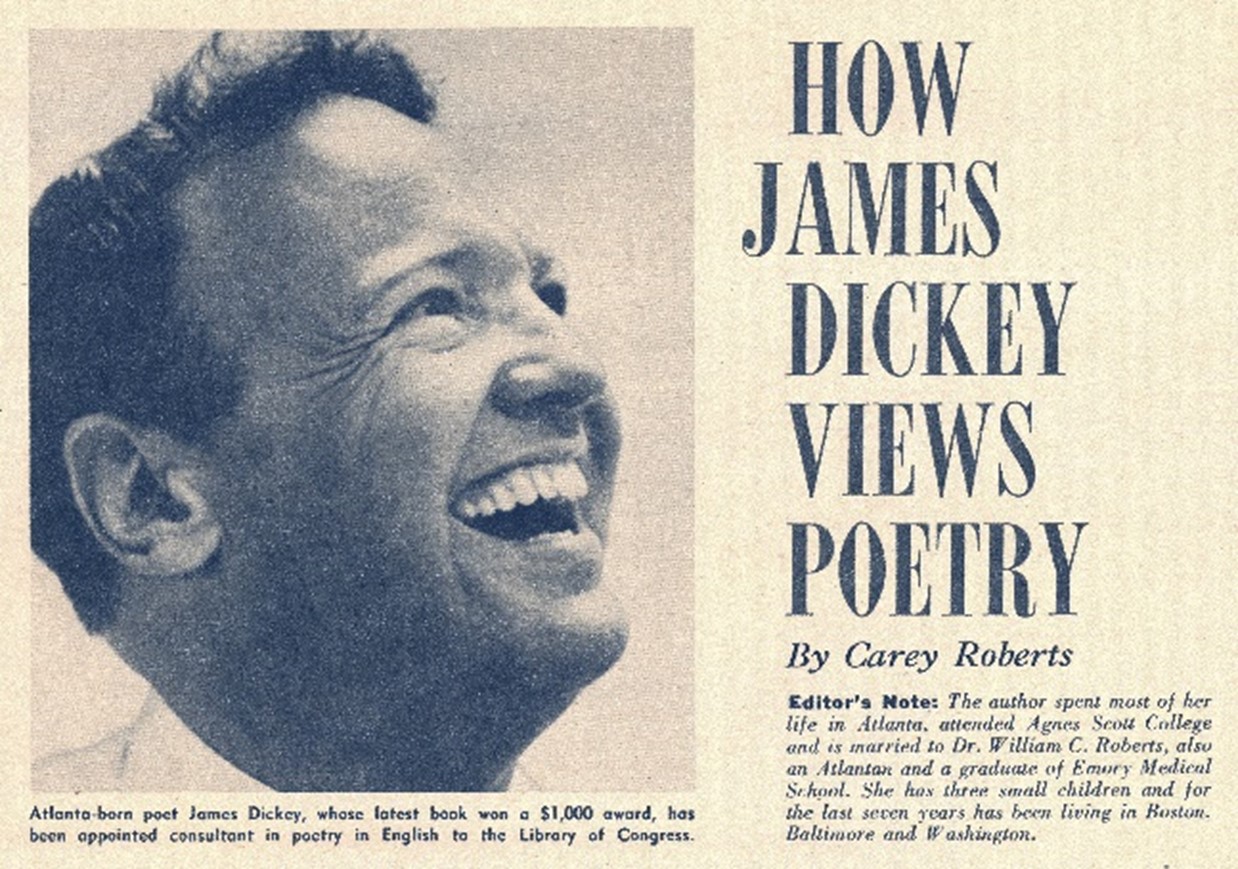

On a different family thread, my mother, Carey Roberts (facing camera), also of Atlanta, published her first of many free-lance articles in the Atlanta Constitution newspaper in 1967 on “How James Dickey Views Poetry,” after the poet had just been named the poetry consultant to the Library of Congress. Her best friend was Eileen Glancy (on the right), also a native of Atlanta, who published a bibliography and critique of James Dickey.

This author had a rather minor connection. The second son of James Dickey was Kevin, a year ahead at Emory Medical School. At his wedding in about 1986 at an Episcopal Church in Savannah, this author met the father, James Dickey. My Uncle Stewart died recently in Atlanta, and I received a lot of books from him, including Buckdancer’s Choice, a hard-cover first edition published by in 1965.

The world was smaller then and the Southern people were more connected to one another. In his poem, “Faces Seen Once,” Dickey writes of himself as “a dull child in Robertstown, Georgia,” a town along the Chattahoochee River in White County, named after Charles Roberts, a wealthy Englishman who mined for gold and established the town. In a riverside park in Robertstown is a memorial erected in 1936 by the Tomochichi Chapter, DAR, to Sydney Lanier [1842-1881], an earlier Southern poet who wrote “Song of the Chattahoochee,” which was read often by my father to me and my siblings at bedside before sleep, to the point that it was memorized.