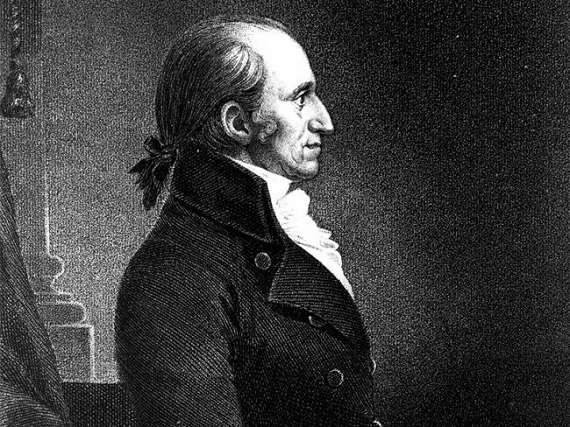

Published in honor of James Jackson’s birthday, September 21.

Delivered in Savannah, in February, 1806, by the Author of this work.

IT is announced to us, that on the 19th day of the last month, departed this life, at the City of Washington, after a long and painful illness, Major General James Jackson, one of our Senators in the Congress of the United States …. Amidst the respectable testimonies of respect which have been paid to his memory, I have been honored with a request to pronounce the eulogy which the merits…. the services and virtues of the deceased entitle him to have recorded, as a just tribute offered up to his past fame, and a security for the recollections of his fellow-citizens.

I hope I shall be able to deliver his panegyric without any deviations from the plain principles of truth and candor.

As the distinguished citizen, whose shade we are now invoking, was incapable of speaking a language which was not founded on the sincerity of conviction, or which did not flow in a direct course from the breast; neither will I, his humble eulogist, trespass one moment on your indulgence to descant upon topics which have no relation to his real virtues; nor will I attempt to attribute traits of character to him which his soul would falsify if it could hover over my head at this moment and assume the attribute of speech. I shall not therefore, swell the panegyric beyond its natural limits, lest in its inundations I bring confusion on myself It is not necessary to deal in fiction on this occasion …. the character of General Jackson stands too high it is too well known by the people of the United States to require either the aid of exaggeration, or the polish of a base flattery. He loved truth and fair dealing for their own sakes, and intuitively detested their opposites.

He was a plain hearted republican, whose tongue knew no guile….whose heart never palpitated with fear, or planned dishonesty.

The most violent personal resentments will always result from the collisions of faction, and men otherwise virtuous, but under the influence of those resentments, will but too often give a currency to political calumnies, and a sanction to measures which ought to be rejected as dishonorable, and condemned as inconsistent with a pure and disinterested love of country. General Jackson has been engaged in scenes which called forth all the rancorous feelings of the heart, and which have given a permanency to feuds which even the grave itself does not cover and annihilate …. feuds which will expire only with the liberties and happiness of this nation. These feuds did not, however, produce all their ordinary effects upon him. Their bitterest spirit has never been able to snatch from the public opinion the impression of his honesty and inflexible integrity. He has sustained the character of an honest man amidst the highest effervescences of party feeling even at times when calumny itself usurped the dominion of sacred truth, and sounded her voice in the temples of God.

The loss of such a character as this, from the humble walks of a private station, (for an honest man is the noblest work of God) is to be most sincerely and deeply regretted by a virtuous and enlightened community …. how loud then ought the lamentations of a nation to be in being deprived of such a man, who filled the highest political stations …. who carried his personal honesty into the circle of his political engagements …. who discharged his public duties by the scale of his individual rectitude.

He despised the machiavelian policy which establishes two kinds of honesty, one for the man, the other for the statesman.

His private and political honesty were homo genius, participated in the same principles or nature.

He respected the arcana of state …. and the mysteries of the cabinet, no further than they were compatible with the public good, or came within the range of his opinions of political morality.

He always dared to speak what he thought, and never deviated from a line of conduct once adopted, from any apprehensions for himself. He was steady, persevering and immovable in the prosecution of his measures not to be swerved from them by the virulence of censure, or the danger of formidable hatreds. If he believed he was right he would go on.

If General Jackson had been accessible to corruption there was a period when he could have commanded an affluence beyond a parallel in this nation and what may appear to many inexplicable, he might have remained in possession of his political ascendancy. Such was the peculiar combination of qualities which concentrated themselves in the character of this celebrated citizen. But gold could not tempt him from his duty…. the estates he had left behind have been acquired by testamentary generosity, or the efforts of industry, not unaccompanied by the prudential cautions of economy. I doubt whether his devotion to public duties, and the interests of his fellow-citizens, has superseded the necessity on the part of his sons to toil as he did. If their patrimony is not as great, however, as it could have been, let the integrity and civic virtues of their father console them for the disappointment. Let them recollect, that they are not the descendants of an unprincipled Satrap, but the honorable offspring of a Patriot Citizen. Let them recollect, and each of my young countrymen, that he has opened a track for them which if followed with honor and firmness will reward them with fame and competency, not with luxury and insolence.

The character and principles of General Jackson are marked with a firmness and consistency rarely discoverable in the actions of statesmen and seldom compatible with that species of ambition which rests for support upon its own nature and energies in opposition to the obstructions which fortune and birth have thrown in the way of its ultimate objects.

The political principles of the deceased in no instance veered with circumstances…. they were above the control of circumstances: for as they were the result of reason, reflection and comparison, they neither changed with a change of men and measures, or floated with the tides of political relations. At the dawn of 1776, and for the whole period of the revolutionary struggles with Great-Britain, he bravely, and to the utmost of his abilities contended for the rights of liberty and independence of this country, and the distance of nearly thirty years did not cool the ardor of his ’76 principles.

He died in 1806, the unalterable, the fervid patriot of 1776…. He drew his last breath at a moment when the situation of this country demanded all his zeal. If he had lived he would have stood in the lists of those patriots who will never sacrifice the legal rights of their country at the shrine of ignoble peace. If I mistake not, no temporary inconveniences to commercial profit, no temporary diminution of the revenue of the United States, would have obtained his assent to any measures which indirectly acknowledged the imbecility of their government, or the pusillanimity of their people. The United States of America can support their rights, and at this crisis he would have said so.

General Jackson believed that the constitution of the United States was the standard, under which our people ought to rally in the hour of danger and alarm: he believed that its principles combined all the energies necessary for defensive or offensive operations. He considered the federal compact as the palladium of American liberty, and venerated it for the irrefragable refutations it had given to the opinions of foreign politicians, that the republican form of government was not suited to a wide extent of country, and that it could not protect itself from external aggressions. He venerated the constitution of the United States, because it consecrated the only form of government, which his reason could assent to.

General Jackson was born an Englishman, but his heart was American. If every native feels the same affection for this country that he did, it is able to protect itself against all attempts on its liberties. The amor vincit patriae, of theorists would then be confirmed, by the operation of practical virtues. He offers a noble example to naturalized citizens, who have solemnly pledged themselves to support the principles of this government. The love of native soil is natural, and it is amiable; but I hope that local attachment will not prevent an honorable discharge of duty, when the dangers and interests of this country demand the services and zeal of my adopted countrymen. They will no doubt do their duty. Having discharged it they will meet the reward which it is in the power of a free people to bestow: and like General Jackson, they will afford this useful lesson to the world, that men can be found in the bosom of this rising republic who know and feel no other obligations than those which result from honor and abstract patriotism …. I mean the patriotism of principle, not of soil. General Jackson was not divested of ambition; but his ambition carried with it no treachery. It was not an ambition which could be soothed by gew-gaws and ribbands.

The distinctions of aristocracy could never have gratified it. It was an ambition, which concentrated itself in a love of the people, and which was unwilling to relinquish any favors within their gift. It was an ambition which eagerly collected all those honors which form the wreath of civic virtue. Is ambition of this kind reprehensible? Is it dangerous to American liberty? I hope not. I believe that it is not. I hope the same ambition will elevate to a proud rank, every citizen of this nation who is influenced by it, and can dignify it with virtue and talents. “Though the pure consciousness of worthy actions, abstracted from the views of popular applause, be to a generous mind an ample reward, yet the desire of distinction was doubtless implanted in our natures as an additional incentive to exert ourselves in virtuous excellence.”

General Jackson had his frailties and imperfections in common with other men. He suffered perhaps the impetuosity of his temper to hurry him into extremes, too often and unnecessarily. Believing that his political tenets were such which every citizen ought to feel, he was impatient under contradictions, and apparently intolerant to his opponents. He did not perhaps take sufficient pains to convince an adversary, or to conciliate his good opinion. His private intercourse was in a great measure regulated by a sympathy of political feeling. But tho’ he permitted occasional triumphs of warmth over his real and natural benevolence of character, and though unbending and impetuous, yet no man possessed a stronger sensibility; it was a chord which vibrated on the slightest touch. When made sensible of an error, no man could evince a more lively sense of regret, or a more ready disposition to expiate it. The smallest advances to reconciliation, buried his resentments. His enmities were open and conducted with candor; his enemies were always apprized of his points of attack. But if he was warm in his resentments, he was no less sincere, fervid and disinterested in his friendships. He possessed the social virtues in an eminent degree; he was the most agreeable of companions, when all other feelings were insulated, save those which sprung out of his natural good humor and great flow of spirits.

In private life, the manners and virtues of the general were of an amiable complexion. He was indeed an affectionate father and husband; and a humane master. In all these relations, and in the discharge of the duties incidental to them, he is worthy of the strictest imitation.

I hope I am not trespassing upon your patience. I feel that my arrangement is desultory and prolix. I might have said much less, and with more method.

A subject however has been assigned me, in which it is difficult to connect the coolness of method with those generous emotions which must animate every heart in reciting the virtues of the dead. I hope I have given no false colorings to, or exaggerated the merits of my departed friend. I have said of my friend: but he was the friend of the American People; he was the sincere friend of the people of Georgia. I have it from himself to say it is written with his own hand, that he particularly loved the people of Georgia; that it was his favorite wish to be thought their lather; that he had given up fortune …. family, and the most lucrative pursuits had made all the sacrifices, to perform only what he conceived to be his duty to the people of Georgia: and that if after death his heart could be opened, Georgia would be legibly read there. This he said and wrote two years ago, when he thought himself on the margin of the grave. But who will doubt his attachment for the people of Georgia upon a principle of personal affection? Are evidences required of this attachment? They are discoverable in every action of his public conduct. Look into the records of the state: he will be there found the enemy …. the immoveable, unconquerable enemy of every species of fraud, monopoly and speculation, which levelled their baneful influence at the best interests and happiness of her citizens and their posterity. I will not dwell with emphasis on this subject. I am apprehensive of awakening feelings, which ought to slumber on this occasion, and which I hope have been buried in the same grave with his body.

I am more solicitous to impress upon the minds of all men; of all parties, that we have lost a citizen who was a patriot from principle; and whose particular affections were fixed on the people of Georgia. Georgians you have lost one of your best friends; a friend who never hesitated to jeopardize his life; or sacrifice his fortune in your service. He walked with you through the fire of an arduous revolution, and if God had spared him, was still ready to assert the rights of yourselves and your children against any succeeding tyranny. I see many of his friends here who have grown grey with him in the practice of an uniform patriotism. The respectable and venerable General McIntosh, went to the bosom of Washington a short time before him; and the course of nature is bringing rapidly on, that awful period, which will number with the dead the remaining phalanx of the ’76 heroes. I see some in this assembly; soldiers of that memorable time, whose span cannot be protracted many years: but they will die with the pleasing consolation of leaving their memory and their honor in the possession of a grateful people, who will ever respect and venerate the one, and endeavor to imitate the other. The grave of the Patriot of 1776, inculcates terrible lessons to the enemies of freedom: it teaches that bravery, supported by justice and animated by the hopes of liberty and independence, will ultimately meet the fostering protection of a beneficent providence; and that it cannot be baffled by the strength of tyrants. The grave of the patriot of 1776, inculcates further lessons it teaches the necessity of unanimity; it teaches us to make all those sacrifices which ordinarily attach us to life; to bear with firmness every privation, in support of our natural rights as men, or the principles of a free government. Thus death itself does not deprive us of our revolutionary hero; we listen to and hear his voice through the cold marble of the tomb.

Washington is physically no more, but his shade is ever present among us; it is ever speaking an audible language; it encompasses the hearts of his countrymen, and as long as honesty is respected, it will continue to controul them by the rules of public virtue and moral rectitude. Let the foreign or domestic Caesar, menace an attack on the constitution and liberties of this nation ; the shade of Washington will present itself, and hurl ruin and confusion on the usurper. It is that great moral cause, which of itself on such an event, would carry with it all the energies of a physical host; and communicate the pangs of a whip of scorpions.

Learn from this example my fellow-citizens, the effects of great and benevolent actions, and endeavor to do your duty to yourselves and posterity.

I have some memoirs before me which go into a detail of the revolutionary exploits of General Jackson. I cannot detain you longer on this occasion by an enumeration of them. They shall speedily be submitted to the public, as well as accounts of his public conduct in the various civil stations filled by him since the organization of the federal government. There will be necessarily connected in a production of this kind, a history of the revolution as it was confined to this state, and a general view of the administration of the general government. This I will undertake to perform.

I shall for the present barely mention, that no officer moving in the limited spheres of command which was given him at different periods of the war, could have performed his duty better…. with more zeal, fidelity and firmness.

In the celebrated action of the Cowpens, he acted as aid to General Pickens, and brigade-major to the Carolina and Georgia militia. In that action he took the swords of several officers, and among them the sword of Major McArthur, the commander of the British infantry, and delivered that officer to General Morgan; and received the thanks of the General for his conduct on the field of battle. This is one; but not the most important, among those achievements, which distinguished the military life of the deceased. It is only mentioned as a general illustration of his ardor, during the revolutionary contest.

General Jackson in his life time, had to stem the torrent of much personal animosity. I hope that his memory has now no resentments to contend with. I hope they will be permitted to moulder with his body there in the dust. The despotism of France, and the recent encroachments of Britain on our independency and legal rights, have annihilated the prejudices that once divided our citizens between those rival powers. The true American, has now no particular predilections for either of those nations; and with the fall of those predilections, have also expired many of those diversities which characterised the sects of democratic and federal republicans. In a common cause the ebullitions of party spirit have subsided. I hope then that this spirit will not be revived to disturb the ashes of my friend. The attendance of many in this assembly does honor to their magnanimity, and convince me, that, that spirit will not be revived.

The respectability of this assembly and the dignity of the pageant, offer up nothing more than a just tribute to the memory of the deceased. This country has lost one of its sincerest and best patriots, and therefore every ceremony evincive of regret for such an event, is but the performance of a duty which a generous people are ever willing to impose upon themselves.

I give you my thanks my fellow-citizens for your patience and respectful attention; and solicit your pardon, for the time I have trespassed upon.