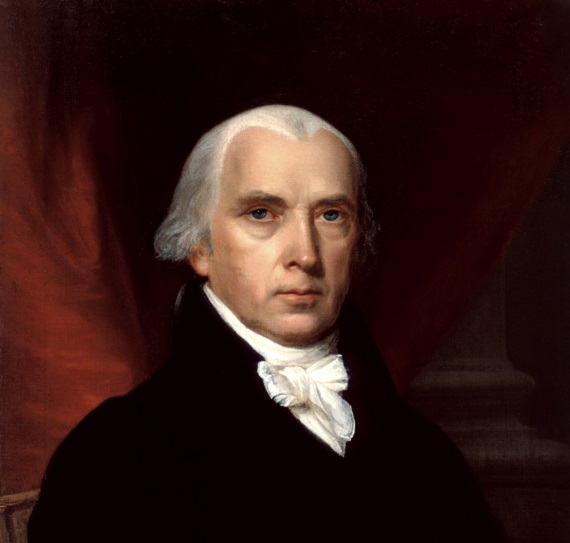

A Review James Madison: A Son of Virginia and a Founder of the Nation by Jeff Broadwater (University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

Speaking at the celebration of the completion of the restoration of Montpelier, Chief Justice John Roberts said, “Montpelier restored is certainly beautiful but is in no sense the most fitting memorial to James Madison. If you’re looking for Madison’s memorial, look around…look around at a free country governed by the rule of law.”

There is no monument to James Madison, the Father of the Constitution, in Washington, D.C. In contrast, the monument to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the man who arguably did the most to dismantle the delicate balance of powers in that document takes up about an acre.

Guess what. James Madison wouldn’t care.

Jeff Broadwater’s recent Madison biography — James Madison: A Son of Virginia and a Founder of the Nation — understands that. Broadwater, a professor of history at Barton College, appreciates the unassuming nature of the man they called “Little Jemmy” (he stood about 5 feet four inches tall and never weighed more than 140 pounds).

To understand why this seeming slight wouldn’t bother the diminutive Madison, take a visit to his grave on the grounds of his Orange County, Virginia. You’ll instantly recognize the humility that was a hallmark of his life. The monument is a small, understated obelisk that mentions none of Madison’s impressive achievements.

In his commendable contribution to the corpus of Madison biographies, one of Broadwater’s primary focuses is on Mr. Madison’s tireless efforts to promote and protect the natural right of men to worship according to the dictates of their own consciences.

Madison’s dedication to preserving religious liberty was demonstrated during his years as a state legislator.

On June 20, 1785, Madison penned an essay putting forth fifteen reasons for opposing a bill in Virginia authorizing the use of public funds to pay “teachers of the Christian religion.” This famous letter is called “Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments.”

Madison took great pains to keep his authorship of the Memorial and Remonstrance secret. He worried that his involvement in the fight to end state-subsidized religion could bring him unwanted confrontation from those with whom he was personally friendly and who believed deeply in the continuation of churches funded by the state government.

Thousands of copies of Madison’s “Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments” were printed and distributed in Richmond. Several others opponents of the bill published similar petitions and a bill that seemed certain to pass just a year earlier, was defeated and in fact never made it to the floor of the General Assembly for debate.

So persuasive and well-reasoned was Madison’s “Memorial and Remonstrance” that one author described the document as “one of the truly epoch-making documents” in American history.

As for the contents of the petition, the pious and prayerful nature of James Madison shines through.

In the first paragraph, Madison lays out what he believes to be the proper boundaries of civil and religious and authority, as well as the proper prioritizing of the duties and obligation owed to both:

The Religion then of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man; and it is the right of every man to exercise it as these may dictate. This right is in its nature an unalienable right. It is unalienable, because the opinions of men, depending only on the evidence contemplated by their own minds cannot follow the dictates of other men: It is unalienable also, because what is here a right towards men, is a duty towards the Creator. It is the duty of every man to render to the Creator such homage and such only as he believes to be acceptable to him. This duty is precedent, both in order of time and in degree of obligation, to the claims of Civil Society.

Next, Madison reminds readers of the necessity of a free people to keep their rulers inside the limits of their authority as determined by the people who are the ultimate sovereigns. Letting leaders roam outside the borders of the consent given by the governed will only end in tyranny, Madison warns:

The preservation of a free Government requires not merely, that the metes and bounds which separate each department of power be invariably maintained; but more especially that neither of them be suffered to overleap the great Barrier which defends the rights of the people. The Rulers who are guilty of such an encroachment, exceed the commission from which they derive their authority, and are Tyrants. The People who submit to it are governed by laws made neither by themselves nor by an authority derived from them, and are slaves.

When the bill safeguarding the right of men in Virginia to define the dictates of their religious devotion, Broadwater records the words written from Madison to his friend and frequent collaborator, Thomas Jefferson:

“I flatter myself [that we] have in this country extinguished for ever the ambitious hope of making laws for the human mind.”

Madison’s experience in the battle in the Old Dominion to protect religious freedom convinced him, Broadwater writes, that “conscience is the most sacred of all property.”

Property was another of Madison’s main concerns and Broadwater mentions the flurry of essays authored by Madison and published in the National Gazette from November 1791 to December 1792.

The last of these essays, written anonymously by Madison, he masterfully made the case for the necessity of holding property rights sacrosanct in a society claiming to be self-governing.

In his treatment of this subject, Madison portrays it as one which “ embraces every thing to which a man may attach a value and have a right; and which leaves to every one else the like advantage.”

Property, Madison explains in finer detail includes “a man’s land, or merchandize, or money,” as well as “his opinions and the free communication of them.”

That is a very expansive definition of property and shines a bright light not only on the Founders’ profound desire to protect property, but on exactly what they meant when they said “property.”

Madison proceeds in this vein to go on to enumerate the various forms of property that a man may be said to possess:

He has a property of peculiar value in his religious opinions, and in the profession and practice dictated by them.

He has a property very dear to him in the safety and liberty of his person.

He has an equal property in the free use of his faculties and free choice of the objects on which to employ them.

In a word, as a man is said to have a right to his property, he may be equally said to have a property in his rights.

With this conception of property provided by James Madison, one more fully appreciates the protections afforded by the Bill of Rights. When the Founders listed “life, liberty, and property” as the three great rights of mankind, with the last of those words they were not speaking simply of the physical terrain a man might possess or plow. They were speaking of the full spectrum of rights a man possesses, as well as his unfettered right to use them as he may see fit, provided he does not thereby infringe on those same rights as possessed by another man.

To James Madison and the men of the Founding Generation, a man’s freedom, then, was no less his property than his farm.

As for how the government of the United States should treat the property rights of its citizens, Madison declares that the government would be unjust if it permitted property to be “violated by arbitrary seizures of one class of citizens for the service of the rest.”

In other words, that government is unjust which establishes a system wherein the laws are manipulated to redistribute wealth from those who work to those who do not.

An effect of the near constant denigration by cultural Marxists and manipulative mockers of the men who in 1861 tried to declare independence from a tyrannical central government is the forcing down the “memory hole” of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, the latter of which was written by James Madison, a Southerner, a republican, and a steadfast supporter of self-government.

The text and tone of the Virginia Resolution is typical of the moderate mien of James Madison. He is sharp, but sincere; courageous, but considerate. More than anything, the resolution recites Madison’s concept of the correct constitutional relationship between the states and the federal government. Madison’s opinion on the subject carries more weight than even that of his cohort, Jefferson, as Madison was present every day in Philadelphia and was an active advocate of many of its provisions, both at the Constitutional Convention and in the Federalist.

And, as fitting for the Father of the Constitution, the Virginia Resolution “doth unequivocably [sic] express a firm resolution to maintain and defend the Constitution of the United States” and “most solemnly declares a warm attachment to the Union of the States, to maintain which it pledges all its powers….”

Then, Madison begins his concise rehearsal of the creation of the Constitution by the states, including the establishment of a federal government in that document, a general government which would serve as the agent of the states. In this regard, the Virginia Resolution reads:

That this Assembly doth explicitly and peremptorily declare, that it views the powers of the federal government, as resulting from the compact, to which the states are parties; as limited by the plain sense and intention of the instrument constituting the compact; as no further valid that they are authorized by the grants enumerated in that compact; and that in case of a deliberate, palpable, and dangerous exercise of other powers, not granted by the said compact, the states who are parties thereto, have the right, and are in duty bound, to interpose for arresting the progress of the evil, and for maintaining within their respective limits, the authorities, rights and liberties appertaining to them.

States, explains Madison, have a responsibility to restrain the government of the United States, to keep the federal beast inside its constitutional cage, so to speak. This responsibility is not to be taken lightly as it is only through the vigilance of the states that the federal government can be kept within the boundaries drawn around its powers by the delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1787.

Madison’s proposal then goes on to express “deep regret, that a spirit has in sundry instances, been manifested by the federal government, to enlarge its powers by forced constructions of the constitutional charter which defines them.”

It is worth noting of the Virginia Resolution that once again, we find the Founders (in this case, one of the Founding Fathers’ Varsity team!) providing a key to solving a contemporary problem, the problem of a federal government that has grown too large and too powerful.

In the end, the state governments of both Virginia and Kentucky passed their respective resolutions, but other states did not follow suit, leaving the lasting solution to the problem of federal overreach for a later generation to face. The solution to which was the absolute reversal of the constitutional roles for the general and state governments established by Madison and his colleagues at the Convention in Philadelphia.

Finally, Broadwater’s biography of the fourth president of the United States and Father of the Constitution laudably attempts to lasso the entirety of the life of James Madison within its 266 pages. Obviously, to deconstruct the philosophy and life of a man as historically relevant as James Madison is a task beyond most any mortal.

Where Broadwater is to be commended is in his apparent aim of illuminating enough of Madison’s mind as to motivate the reader to pursue a deeper dive into the ocean of intellectual, philosophical, and political preeminence of one of the least enigmatic and least celebrated of Virginia’s vaunted sons.