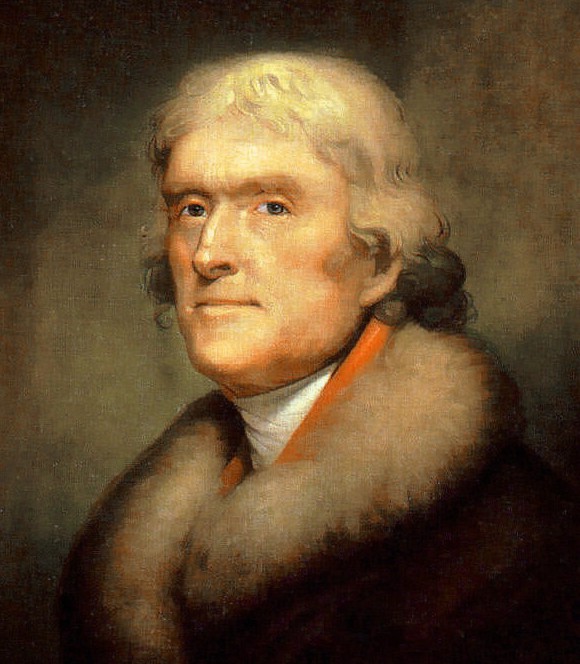

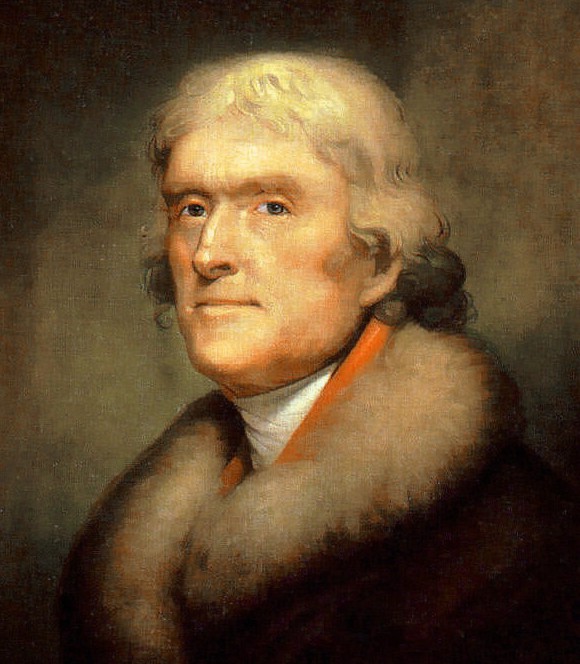

President Thomas Jefferson’s first inaugural address articulated his philosophical manifesto: “Peace, commerce, and friendship with all nations – entangling alliances with none.” These basic maxims were stressed repeatedly by Jefferson, who cherished a commercially free country that would avert the costly European wars of the past. Optimally, Jefferson hoped to avoid foreign conflicts completely.

Jefferson had long championed the idea that conquest and imperial pursuits, which had consumed Europe for centuries, was to be avoided in America. Writing to his friend Thomas Paine in 1801, he put it this way:

“Determined as we are to avoid, if possible, wasting the energies of our people in war and destruction, we shall avoid implicating ourselves with the powers of Europe, even in support of principles which we mean to pursue. They have so many other interests different from ours, that we must avoid being entangled in them. We believe we can enforce these principles as to ourselves by peaceable means, now that we are likely to have our public councils detached from foreign views.”[1]

As a young country without a strong military presence, at its infancy the United States was exposed to stresses that would shape its early actions on the foreign stage. Deficient to protect itself, contemporary Americans would have no conception of these inadequacies, and find this situation unrecognizable. Before he was president, Jefferson was already familiar with these circumstances, and was accustomed to the practices of the Barbary pirates.

After the states lost the protection of the British navy through their independence, American sailors were especially vulnerable to capture. In 1795, Algeria captured 115 sailors and demanded a tribute for $1 million, a huge sum of money at the time. Sailors were held in poor conditions, food was scarce, and disease was rampant. In 1786, the Confederation government sent Thomas Jefferson and John Adams to negotiate with the Tripoli to prevent future hostilities.

When they asked the envoy the reasoning concerning the hostile actions, ambassador Sidi Haji Abdrahaman responded:

“It was written in their Koran, that all nations which had not acknowledged the Prophet were sinners, whom it was the right and duty of the faithful to plunder and enslave; and that every mussulman who was slain in this warfare was sure to go to paradise.”[2]

The pirates were in no mood for negotiation, and they strongly maintained that their religious beliefs obligated them to make war upon non-Muslims. For his part, Jefferson believed that capitulating to the demands of the pirates would simply encourage future kidnappings, and advised against making the payments. However, the United States was in no position to clash with an opponent on the high seas – it had no virtually no navy and its financial resources were exhausted. Strained by debt from the war with Britain, the United States continued to pay the $1 million figure for the next 15 years.

During some of this timeframe, American vessels enjoyed the protection of the French navy as a result of the Franco-American alliance. This perk changed during the Washington and Adams administrations, as relations with France soured and the two powers engaged in a series of naval clashes in 1798. Ultimately, the Quasi War was resolved through the 1800 Treaty of Mortefontaine, but American ships never again enjoyed the protection of a superior navy.

Early in his presidency, Jefferson was thrust into a second test concerning the pirates that could have challenged his principles regarding foreign policy. Unprovoked, Barbary Pirates had captured and enslaved American sailors and demanded excessive ransom payments. As a fledgling country, America was faced with one of its first true foreign predicaments. Once in the presidency, would Jefferson uphold his political philosophy by carrying out foreign policy in a manner that was consistent with the Constitution?

Clearly, those who wrote and explained the document purposefully confined war powers to Congress. In Pennsylvania’s ratification convention, prominent Federalist James Wilson assured the delegation that war-making authority would “not be in the power of a single man.” Beyond this, he noted:

“The important power of declaring war is vested in the legislature at large: this declaration must be made with the concurrence of the House of Representatives: from this circumstance we may draw a certain conclusion that nothing but our interest can draw us into war.”[3]

Similarly, in The Federalist #69, Alexander Hamilton described the president’s authority this way:

“His authority would be nominally the same with that of the King of Great Britain, but in substance much inferior to it. It would amount to nothing more than the supreme command and direction of the military and naval forces, as first general and admiral of the confederacy; while that of the British king extends to the declaring of war, and to the raising and regulating of fleets and armies; all which by the constitution under consideration would appertain to the Legislature.”[4]

No alternative narrative concerning the executive was ever presented in the state ratification conventions, and despite widespread skepticism and apprehension concerning the office, the states ratified the document under the postulation that the president could not wage his own wars or engage in military excursions without explicit congressional authorization.

This was a wise decision, reached by observing the tragedies of the past. Through the annals of western history, powerful executives were prone to abusing war powers. It allowed them to conscript armies, drain national treasuries, and curtail individual liberty under the guise of heightened security. The tendency created continual civil disputes that ended in much bloodshed, such as those between Charles Stuart and the Long Parliament of England. Certainly, an executive with the power of a hereditary monarch was a recipe for disaster that the founders sought to avoid.

Jefferson, to his credit, wished to deviate from the kings of old by walking a different pathway in pursuit of republicanism. Still, the lack of American naval protection afforded the Barbary States an enticing opportunity. Without viable security to protect them, American sailors would be vulnerable targets for extortion and tribute payments.

Jefferson’s response to the problem would be critical for several reasons. For the country, it would determine whether America had the ability to alleviate such international quandaries. For Jefferson’s philosophy, it would help answer the question of whether the expansion of executive power in wartime was inevitable. Assuredly, the plausibility of republicanism was at stake.

The young United States Navy, which consisted of six frigates, was operational by the time Jefferson was sworn in as president. Prior to his presidency, Congress passed naval legislation that authorized the ships to “protect our commerce and chastise their insolence—by sinking, burning or destroying their ships and vessels wherever you shall find them.”

Upon Jefferson’s refusal to pay Tripoli’s new demand of $225,000, tensions flared. Jefferson sent three frigates and one schooner under the command of Commodore Richard Dale to attempt to maintain peace and engage in diplomacy with the Barbary States. In the event of aggression, Dale was instructed to protect the ships and their crew from hostility by taking responsive action against the pirates.

In response, Pasha Yusuf Karamanli of Tripoli declared war on the United States on May 14, 1801. Ironically, unlike under the American constitutional system, the Pasha could personally declare war against an enemy country. As a symbolic gesture, he cut down the American flagpole in front of the American consulate.

Using the power that was already authorized by Congress, Jefferson was steadfast in his pledge to demonstrate America’s commitment in the matter. Still, he pledged that he was “unauthorized by the Constitution, without the sanction of Congress, to go beyond the line of defense.” Recognizing that only Congress had the power to authorize offensive military attacks, Jefferson communicated this message:

“I communicate all material information on this subject, that in the exercise of this important function confided by the Constitution to the Legislature exclusively their judgment may form itself on a knowledge and consideration of every circumstance of weight.”[5]

In the years to come, Jefferson unfailingly deferred to Congress in matters concerning the Barbary pirates. Evidently, Jefferson thought that America’s resolve could be demonstrated while still abiding by the dictates of the Constitution.

Because of Jefferson’s reluctance to pursue the engagement with more vigor, then-retired Alexander Hamilton took the opportunity to criticize the president. Writing to the New York Post under the pseudonym of Lucius Crassus, he inquired, “What will the world think of the fold which has such a shepherd?” This was written just after a significant victory was achieved – the USS Enterprise had defeated a Tripolitan corsair without the loss of life, and the Americans had established a blockade of Tripoli. According to historian and preeminent Jefferson biographer Dumas Malone, Jefferson’s actions during this endeavor establish that “there are insufficient grounds here for characterizing the president as a timid and foolish shepherd.”[6] Hamilton seemed to be grasping at straws.

Still, the fight was not over. Congress passed additional legislation in 1802, authorizing the president to:

“Equip, officer, man, and employ such of the armed vessels of the United States as may be judged requisite by the President of the United States, for protecting effectually the commerce and seamen thereof on the Atlantic ocean, the Mediterranean, and adjoining seas.”

Additionally, the president was given the capacity to “subdue, seize, and make prize of all vessels, goods, and effects belonging to the Bey of Tripoli,” and “to cause to be done all such other acts of precaution of hostility as the state of war will justify, and may, in his opinion, require.” The law intended to allow for the continuance of the current policy, and reiterated its constitutional legitimacy. At no point did Jefferson take independent military action beyond the bounds prescribed by Congress. In fact, Congress seemed willing to impart authority to the executive beyond what Jefferson had requested.

While the engagements with the Barbary powers continued intermittently throughout the next few years, Jefferson’s diligence paid off in the end. There were a small amount of American losses, but the pirates never resumed their foothold over American interests until after the War of 1812. Jefferson’s stand against the pirates was effective, and the conflict’s toils were largely kept out of sight of the American people.[7] The successful endeavor surely dissuaded European powers from meddling with the young country without good reason, and prevented farther extortion by the pirates. In addition, Jefferson never used the engagement as a pretext to curtail individual liberty like so many of his successors would do.

Some historians have opined that the result of the Barbary crisis elevated America to a new position on the world stage, and solidified its prominence as a world power. They are not totally inaccurate, but this situation brought forth a blessing and a curse. Jefferson proved executive expansion during wartime was not inevitable, but America’s naval successes on the high seas were short-lived. A decade later, the British outmaneuvered the American navy during the War of 1812, where some naval successes were overshadowed by the inability to form a blockade against the British.

Refusing to go past the line of defense prescribed by Congress, Jefferson fostered an encouraging early example for how the executive was to carry out foreign policy. In contrast, today’s presidents unilaterally send forces all throughout the world to achieve foreign policy goals without the direction of Congress. They constantly cite the constitutional transgressions of their predecessors as justification for their actions. This is often done even in the face of congressional opposition.

While all modern presidents should recognize Jefferson’s refusal to usurp war power, they haven’t done so for over a century. Still, it behooves all Jeffersonians to point to this incident as a quintessential proof of the potential for republican government to exist under an executive that understood the confines of the Constitution. The discipline maintained by Jefferson during this ordeal undoubtedly exemplified the plausibility of an executive much unlike all hereditary monarchs in the world at the time.

[1] Thomas Jefferson to Thomas Paine, Quoted in The Life and Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Edited by S.E. Forman (Indianapolis: Bowen-Merrill Company, 1900), 215.

[2] “American Peace Commissioners to John Jay,” March 28, 1786, Thomas Jefferson Papers, Series 1, General Correspondence. 1651–1827, Library of Congress.

[3] The Debates in the Several State Conventions on Adoption of the Federal Constitution, Edited by Jonathan Elliot, Volume II, (Washington: Taylor & Maury, 1861), 488.

[4] The Federalist #69, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, The Federalist, Edited by Jacob E. Cooke (Middletown: Wesleyan University, 1961), 465.

[5] First Annual Message, in Thomas Jefferson, Thoughts on War and Revolution, Edited by Brett Woods (New York: Algora Publishing, 2009), 157.

[6][6] Dumas Malone, Jefferson and His Time, Volume Four: Jefferson The President, First Term, 1801-1805 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1970), 98-99.

[7] Ibid, 263.