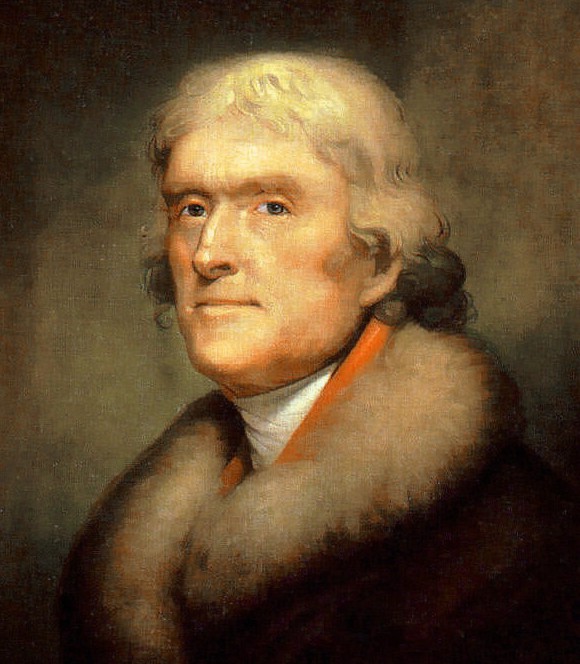

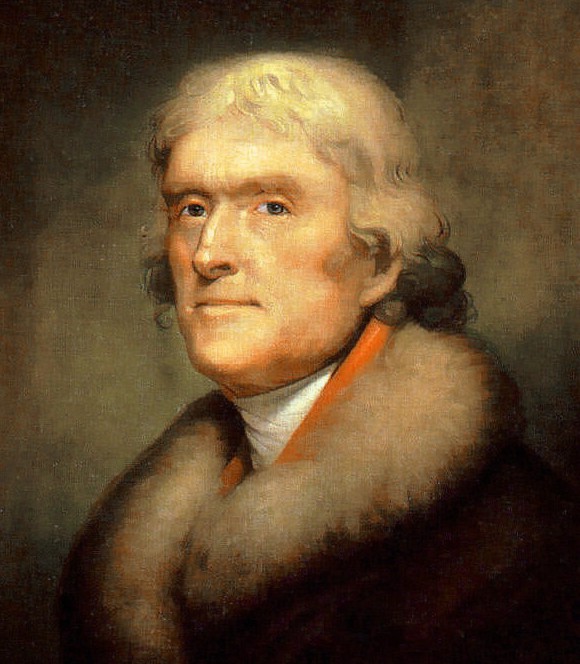

Thomas Jefferson is perhaps the greatest enigma of the American age. He wrote and spoke on so many topics that he has become the symbol of virtually every strain of uniquely American political thought. Jefferson is the democrat, the agrarian, the federalist, the republican, the radical, the conservative, the statesman, the planter, the intellectual, the philosopher, the educator. Volumes have been written on his life and legacy, and yet we still search for the man. More will be written, but somehow his name will remain both predictable and elusive, like the bite of the first frost, the first bud of spring, the first warm Southern summer day. We know it is there and that it will come, but when is always a mystery. Jefferson is the crackling log and a warm hearth on a cold day, the reliable anchor to our ship of state. We know him because he is us. Even now, as many Americans attempt to demonize and jettison his name and legacy, to reduce him to little more than a vicious slave holder with a cunning and vindictive stripe, Jefferson has currency in our age if we choose to listen.

Next to Washington, he is the most American of the founding generation, and his name defined a later generation of Americans. Long before the Age of Jackson, there was the Age of Jefferson, the boundless and restless American foray into the great frontier, peopled by farmers and a hearty individualism that became the hallmark of the American experience. Jefferson embraced it like no other, and in contrast to Jackson, Jefferson knew how to articulate a vision. Jackson rode Jefferson’s coattails, reacted to and then rejected Jefferson’s American man, the free thinker, the independent spirit, the American statesman guided by a brand of republicanism that was purely American.

If Jefferson bequeathed anything to America, it is not the proposition that “all men are created equal.” Equality under the law had been an accepted maxim long before Jefferson wrote that line in the Declaration of Independence. No, Jefferson’s gift to America is found in the last paragraph of the Declaration, the firm commitment to a federal republic of “Free and Independent States” comprised of the people who made each community unique. This is Jefferson as the conservative.

Jefferson believed that States were organic communities built on a common culture. He could be a radical within his own community but it ended there. Whereas Jefferson had a grand vision for the “Empire of Liberty,” that was only in relation to the idea of independence. It was not a “city upon a hill” sermon of subjugation. Jefferson, in his “flatteries of hope” thought the “ball of liberty” would one day “roll around the globe” and as he wrote to John Dickinson in 1801, Jefferson believed that, “A just and solid republican government maintained here will be a standing monument and example for the aim and imitation of the people of other countries; and I join… in the hope and belief that they will see from our example that a free government is of all others the most energetic; that the inquiry which has been excited among the mass of mankind by our revolution and its consequences will ameliorate the condition of man over a great portion of the globe.” Yet, he was under no illusion that such would be easy or in every case desirable. He did not think republicanism would take hold in South America nor did he think that everyone the world over would embrace liberty. It was the American condition, and maybe only the Virginian condition, which is why he wanted Southerners to avoid the “dark Federalist mills of the North.” If so, Jefferson would defend it in his own country to the last.

His dedication to the American order is evident in his various statements on political philosophy. His grand statements on federalism and “nullification” in the Kentucky Resolutions are consistent with a belief in the necessity of community and the people as the safeguard of liberty. He wrote in 1809 that, “The people of every country are the only safe guardians of their own rights, and are the only instruments which can be used for their destruction. And certainly they would never consent to be so used were they not deceived. To avoid this they should be instructed to a certain degree.” The Sedition Act was not only unconstitutional, it violated the ordered liberty of Virginia, and was an attempt by a foreign power (New England) to impose its will on another people. Jefferson the philosopher rejected such cultural imperialism, just as he rejected the cultural imperialism of Great Britain in 1776. He later said that the Declaration was not a radical pronunciation of new rights but simply the articulation of the American mind. In Jefferson’s case that mind was forged in the hardwood covered hills of Virginia.

Jefferson’s Northwest Ordinance and his support for political independence provide ample evidence that his “democracy” was rooted in the culture of a people and the voice of a place. When each territory in the old Northwest reached five thousand free male inhabitants, it could form a government, with a representative ratio of 500 to 1. Such a government would be responsive to the community and the culture that created it. It would be democratic in its purest form. In contrast to a “national democracy,” this type of democracy could be controlled from within by neighbors in a republican experiment. Once the territory reached sixty thousand free inhabitants, it could be admitted to the Union as a State “on equal footing with the existing States.” The people would then form a constitution and a republican form of government, but such States and the government thereof would be the expression of the political community and not of the Union as a whole. As in Virginia, the constitutions of these new States would be formed by the culture of the people who resided therein.

Jefferson later said that the political culture of each new State may in time sever its ties to the old American Union. That was perfectly reasonable, logical, and ultimately preferable. He had his own reason to worry about a Union of incompatible things. The “fire bell in the night” Jefferson famously warned against was not a fear over eradication of slavery per se, but over the potential cultural imperialism of the North and the destruction of true federalism. If States could be coerced by a numerical majority, then the culture of each would be ground into grist by alien peoples and alien agendas. Jefferson did not want other political communities to fall prey to this type of political suicide. Separation would be preferable to cultural destruction.

That alone made Jefferson a conservative. He could wax philosophical about changing the culture of his own backyard, and many of his contemporaries viewed his political theories as radical departures from the status quo, but Jefferson never sought to apply those theories to Massachusetts or Pennsylvania. He was a cosmopolitan thinker knee deep in Virginia soil and eye level with his mountains. Modern Americans should learn from such a vision. He would sweep his own backdoor but leave it to someone else to sweep theirs. Jefferson’s federalism is the American vision of political unity, a unity that was only perverted by the social engineers, do-gooders, and reformers intent on remaking the rest of the world in their image. Jefferson was not this type of activist, nor did he possess the Puritanical crusading zeal of New England.

His America held for more than eighty years, and even after a brutal war that claimed the lives of a million men, there were those, North and South, who formed a truly national vision of the American spirit. These Jeffersonians still exist, principally in the small towns and rural pockets of the American landscape. The South has remained dedicated to Jefferson’s vision longer than anywhere else. Its small farms and main streets have only recently been occupied by Wall Street corporations, big banks, and cultural Marxists. If anywhere should lead a Jeffersonian renaissance in America, it is the South. Federalism is catching fire in America again. Jefferson’s name, so long vilified by the modern left, is echoing in American political chambers. The slumbering spirit of American self-government has found its voice, if only a whisper now. It can and will eventually roar. Jefferson will have the final say, and we may finally understand who he was and who he is.