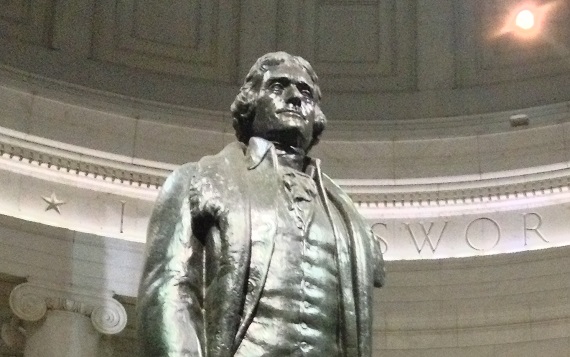

Jefferson was ever committed to tripartite governmental powers, comprising an executive, the legislature, and the judiciary. Each branch, he asserts to George Wythe (July 1776), should be independent of the others to offer itself as a check on the others. The independence of the executive from the legislative is of utmost importance, for otherwise the executive might have undue influence on legislative matters or the legislature, or one party of it, might have undue influence on executive matters. The judiciary, he writes in his autobiography, must be independent of the executive, otherwise it is merely a tool of his bidding, but he adds in a letter to judge Spencer Roane (6 Sept. 1819), it is not to be “the last resort in relation to the other departments of the government,” otherwise, one branch of the government will have control of the other two and that is political despotism. An illustration is the judiciary being granted the sole right to interpret the Constitution: for example, concerning the Sedition Act. He tells Abigail Adams (11 Sept. 1804):

The opinion which gives to the judges the right to decide what laws are constitutional, and what not, not only for themselves in their own sphere of action, but for the Legislature & Executive also, in their spheres, would make the judiciary a despotic branch.

What is to be done when the three branches differ in their interpretation of the Constitution? In such an event, agreement by any two overrides the dissenting other (TJ to Don Valentine de Foronda, 4 Oct. 1809).

What of the executive?

The function of the executive is to conduct those matters delegated to him by the constitution: chiefly, foreign affairs—“the President being the organ of our nation with other nations”—comprising international commerce, war and peace, fiscal affairs pertaining to the confederation but not to the individual states, etc. His cabinet tackles issues of weight, each member overseeing affairs within its purview: secretary of state affairs of the federal state, secretary of war affairs of war, and secretary of the treasury fiscal affairs of the federal government. He says to William Short (12 June 1807):

In the gravest cases calling them [members of his cabinet] together, discussing the subject maturely, and finally taking the vote, on which the President counts himself but as one.

Beneath members of the cabinet, there are departmental heads that tackle minor issues “on consultation with the President alone.”

Jefferson was always a minimalist vis-à-vis any form of government. The US president was to be in some measure a federal figurehead to represent the interests of the people. He was primus inter pares (first among equals) a steward, and not one better than those he represented.

In a government like ours, it is the duty of the Chief Magistrate, in order to enable himself to do all the good which his station requires, to endeavor, by all honorable means, to unite in himself the confidence of the whole people. This alone, in any case where the energy of the nation is required, can produce a union of the powers of the whole, and point them in a single direction, as if all constituted but one body and one mind, and this alone can render a weaker nation unconquerable by a stronger one.

To unite the people through confidence in his integrity, Jefferson writes to John Garland Jefferson (25 Jan. 1810), is one of the cardinal functions of the executive:

the very first measure is to satisfy them of his disinterestedness, and that he is directing their affairs with a single eye to their good, and not to build up fortunes for himself and family, and especially, that the officers appointed to transact their business, are appointed because they are the fittest men, not because they are his relations.

Disinterestedness is essential. For the most part, the executive of a nation or a state is a passive receptor which, when actuated, acts pursuant to the interests of the majority opinion of the citizenry. He is thus likened to a calculating machine whose outputs are determined by its inputs. All hints of prejudice must be absent.

Yet there are instances when executive action cannot be determined by a majority vote—instances involving the wellbeing of the citizenry in which the citizens are largely ignorant of relevant information. That is when an executive’s cabinet comes into play.

Jefferson followed the lead of George Washington in his view concerning how a president ought to interact with his cabinet. A president will consult on fiscal business with his secretary of treasury, on military matters, with his secretary of war, &c. On grave matters, he will typically meet with all his cabinet, separately or assembled, for discussion and a vote—best given in writing. Washington would customarily follow the majority vote, but he would decide the issue when two were pro and two were con. He writes to Dr. Walter Jones 15 Mar. 1810):

I practised this … method, because the harmony was so cordial among us all, that we never failed, by a contribution of mutual views on the subject, to form an opinion acceptable to the whole. I think there never was one instance to the contrary, in any case of consequence. Yet this does, in fact, transform the executive into a directory.

By transformation of the executive into a directory, Jefferson alludes to France’s Directory of Five, comprising France’s executive from 1795 to 1799. The objection is the president becomes a councilor, not a “president”—that is, not one who presides. Jefferson replies that the early governors of Virginia acted similarly to Washington—“[they] did what was equivalent in effect”—but with a different understanding of that action. When the governor’s advisors were deadlocked, the governor would decide an issue, but not as one of his councilors, but as the executive. He tells James Barbour (22 Jan. 1812):

While I was in the administration, no doubt was ever suggested that where the council, divided in opinion, could give no advice, the Governor was free and bound to act on his own opinion and his own responsibility.

War, of course, was a constitutional complication. Jefferson cites the invasion of Virginia by Cornwallis during his tenure as governor. The invasion caused a separation of Jefferson and his councilors. Jefferson was left to decide and act on his own, which the Virginian constitution did not sanction. Jefferson’s successor, Governor Nelson, went so far to impress men into the army for the defense of Virginia, and that was beyond the enumerated powers of the governor. Jefferson, in defense of his own and Nelson’s actions, continues to Barbour.

Indeed, it is difficult to suppose it could be the intention of those who framed the constitution, that when the council should be divided the government should stand still; and the more difficult as to a constitution formed during a war, and for the purpose of carrying on that war, that so high an officer as their Governor should be created and salaried, merely to act as the clerk and authenticator of the votes of the council. No doubt it was intended that the advice of the council should control the governor. But the action of the controlling power being withdrawn, his would be left free to proceed on its own responsibility.

In sum, when dire circumstances prohibit an executive from meeting with his councilors, exigency requires quick executive action, to be judged right or abusive later, and not delay.

Jefferson continues to Barbour:

Where from division, absence, sickness or other obstacle, no advice could be given, they could not mean that their Governor, the person of their peculiar choice and confidence, should stand by, an inactive spectator, and let their government tumble to pieces for want of a will to direct it. In executive cases, where promptitude and decision are all important, an adherence to the letter of a law against its probable intentions, (for every law must intend that itself shall be executed,) would be fraught with incalculable danger. Judges may await further legislative explanations, but a delay of executive action might produce irretrievable ruin.

Matters of legislation and of the judiciary can often be delayed without danger. It is otherwise with some matters of the executive. What if a state or a nation is threatened with demise?

Can it be believed to have been the intention of the framers of the constitution, that the constitution itself and their constituents with it should be destroyed for want of a will to direct the resources they had provided for its preservation?

In dire circumstances—when a state and its constitution are threatened with nullity—“construction must be made secundum arbitrium boni viri (following the judgment of a good man), and the constitution be rendered a practicable thing.”

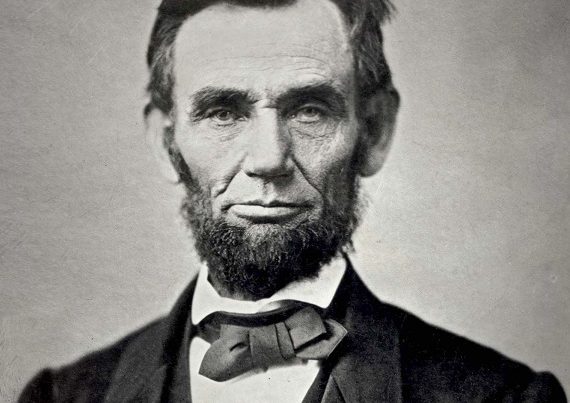

“In dire circumstances—when a state and its constitution are threatened with nullity—“construction must be made secundum arbitrium boni viri (following the judgment of a good man), and the constitution be rendered a practicable thing.” so this wouldn’t apply to lincoln? a constitutional level (9 states?) union still existed…not under threat, iow. as states acceded some also seceded.

TJ always championed secession, but with regrets, for secession would mean that his vision of an “empire for liberty” might be faulty–viz., that representative government can be large and very strong. Always a states’-rightist.

Can’t put Biden anywhere near Jefferson. Trump. On the other hand, seems to be acting more, much more, in the interest of saving our Republic – whether he is aware of it or not. While no where near as eloquent as Jefferson – his presidential library may not have any books – he is a compassionate street wise New Yorker.

I post on my LinkedIn page that we just might have won a second Civil War. The South, that is. People don’t know what to do with it 🙂

Mann:

Ask yourself: Is Trump for small government, a weak executive, states’ rights, &c.? I am sure Jefferson would be appalled by the situation, plutocracy, today. Just a thought….